John Ford gave western fans a version of the Civil War in

this film starring John Wayne and William Holden. At two hours, it’s an

entertaining film without being over-ambitious. And without exactly doing justice

to the subject, it manages to tell its story in a way that does not discredit either

the Union or the Confederacy.

You realize watching it that there have been few movies

about the Civil War since Gone with the Wind (1939). While the U.S. Army fighting Indians was for a long time standard fare on the screen, seeing those same soldiers shooting at other

white Americans is something else again.

Ford chose wisely when he picked the novel The

Horse Soldiers by Harold Sinclair (1907-1966). The book was based on

Grierson’s Raid in 1863, during which 17,000 Union troops traveled from

Tennessee across Mississippi to Union-held Baton Rouge doing damage to

Confederate infrastructure.

Plot. There are

three engagements in the film, one as a trainful of armed men attempts to

defend the town of Newton’s Station. A charge down the main street into

withering gunfire leaves many casualties. A makeshift hospital is organized to

tend to the wounded, with the help of a local doctor. Meanwhile, the Union

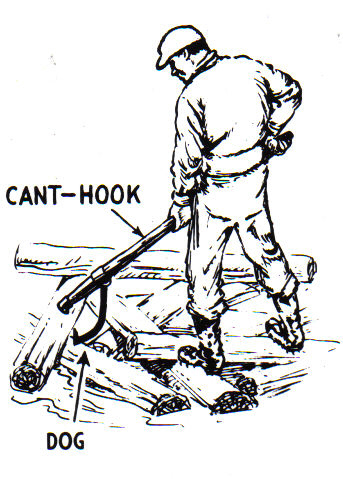

soldiers’ destruction of the town’s rail line is sobering in its thoroughness.

|

| Willian Holden and Constance Towers |

Following that, the boys of a military academy attempt a

courageous though foolhardy attack on the Union troops. It’s a relief when the

soldiers react in disbelief and then make a quick retreat before any lives are

lost. Finally, at the end of the film, an outnumbered contingent of Confederate

soldiers attempts gamely to prevent the Union troops from crossing a bridge.

Most of the conflict in the film, however, is between the

colonel (John Wayne) and an Army surgeon (William Holden). They are at cross-purposes

from the first scene in which they meet. Wayne was a civil engineer for the

railroad before the war; Holden was a graduate of West Point. Just about

everything separates them, from class to temperament.

Amplifying the conflict is Constance Towers as a Southern

belle, who happens to overhear Wayne’s plans to strike across enemy territory

to Baton Rouge. To keep her from telling anyone what she knows, Wayne is forced

to take her and her maid along. Her presence is a constant source of irritation

to him.

Before all is said and done, she begins to have a change of

heart about him. She seems sorry to see him go as she and Holden stay behind

with the wounded, to be overtaken by the Confederate troops who are on their

trail. Glad to be finally rid of her, Wayne makes a courteous but not unhurried

exit. There’s no kissing.