Review and interview

Fallibility. After reading from Richard Wheeler’s lengthy list of historical western novels, I’m thinking fallibility is a special interest of this award-winning author. And it’s a difficult subject in a field of fiction that traditionally wants to pay tribute to the men who opened the West. In this story of Lewis and Clark, however, we are given a portrayal of exceptional men, who are also only human.

Fallibility. After reading from Richard Wheeler’s lengthy list of historical western novels, I’m thinking fallibility is a special interest of this award-winning author. And it’s a difficult subject in a field of fiction that traditionally wants to pay tribute to the men who opened the West. In this story of Lewis and Clark, however, we are given a portrayal of exceptional men, who are also only human.

Eclipse, published in 2002, tackles the story of the

suicide of Meriwether Lewis, only a few short years after the triumphant return

of his expedition to the Pacific with Will Clark. As Wheeler notes in a

Postscript, his death had long been a mystery, some historians advancing

evidence of foul play. As a close associate of Jefferson and the political camp

opposed to Aaron Burr, he would have had his enemies.

But opinion has

shifted to a belief that at the time of his death, Lewis was in fact dying of

syphilis, contracted while consorting with an Indian woman. Wheeler’s novel

begins with the return of the Corps of Discovery and follows Lewis as the

disease eventually ravages his body and mind. The novel’s considerable

achievement is that it makes of this unlikely material a wholehearted and

compelling tragedy.

|

| Meriwether Lewis, c1807 |

In Wheeler’s hands,

it is also a personal tragedy. What destroys him as much as the disease is the

abject shame of being the host of a venereal infection. Lewis sees his hopes

and dreams torn from him, leaving him unfit for marriage and unable even to

confide in his closest friends. He is an exile, a prisoner suffering solitary

confinement. One is reminded of the stigma and the moral panic unleashed with

the first victims of the AIDS virus.

Plot. After their return to the States, Lewis and

Clark are given administrative duties over upper Louisiana. Both are based in

the former French colonial city of St. Louis. Lewis is appointed governor, and Clark

is superintendent of Indian Affairs. Both have immediate and pressing

responsibilities. Chief among them is the winning of allegiance from the many

Indian tribes even as the British, Spaniards, and others contend for control of

the vast tract of land.

|

| William Clark, 1810 |

Meanwhile, he sets

himself unsuccessfully to winning a wife, someone not only arrestingly lovely,

but serious as he. But the few who qualify find him strangely off putting. He

exhibits a social awkwardness that may be related to his anxieties over his

unsettled health. He attributes his symptoms to “ague,” while believing himself

cured of “the pox.”

Arriving in St.

Louis, he is greeted by his second in command, a secretary named Bates, who

wants Lewis to be no more than a figurehead. A man with aspirations of his own,

Bates has intentions for the government of the territory that are in direct

opposition to Lewis’s. In time, his open hostility to Lewis produces a state of

siege between the two men. It’s a situation that mystifies Clark, who remembers

how Lewis was unreservedly loved by the men of the Corps.

Then there is the

matter of the expedition’s journals, which Lewis has promised Jefferson and the

scientific community to rush into print. His job is to edit the daily notes

taken by Clark and himself, a formidable task given the three years of the

journey. But despite Jefferson’s continued urging, he finds himself strangely

unable to even start the task.

|

| The levee, St. Louis, 1857 |

As a man of

achievement, he is also not without ego. He has been encouraged by others to

regard himself as having potential for high office, even one day being asked to

run for president. At one point,

he considers a potential wife as being worthy of joining him some day in the

White House. And he dresses for success, spending his scant earnings as a

government employee on fancy duds.

More devastating for

him financially are his impulsive investments in real estate and other

ventures. When the fur trade

suddenly goes into recession and a stingy War Department stops paying for

expenses he has incurred as an agent of the government, he acquires a mountain

of debts. To his credit, he determines to honor them to the last dollar, but

financial ruin becomes the mirror reflection of the ruin of his mind and body.

Clark comes across as more sensible and even-tempered, his judgment more measured. He is lucky in marriage and more grounded professionally. His respect for Lewis as colleague and friend never falters. When he slowly learns the truth of the man’s condition, including his dependence on alcohol and opiates, he remains loyal and supportive.

|

| Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, 1905 |

While York believes

he has proved himself a man, worthy of his freedom, Clark regards him as no

more than a child. Now that he’s married and has increasing responsibilities,

Clark needs him more than ever, and he refuses him conjugal visits with his

wife on the home plantation. It becomes a battle of wills that parallels the

plotline between Lewis and Bates.

Structure and

style. Wheeler’s special

narrative gift is the ability to immerse us in a story about fallible men and

to make it hard to put down. One of his choices is to tell the story in the

first person, alternating between the points of view of both men. Thus, for

Lewis, we swing between his emotional highs and lows as he struggles between

fear and denial.

Also effective is

how the men narrate the story, as if reporting what has just happened, so that

events unfold for us only a beat or two after their occurrence. That has a

subtle effect, producing an uncommon sense of immediacy.

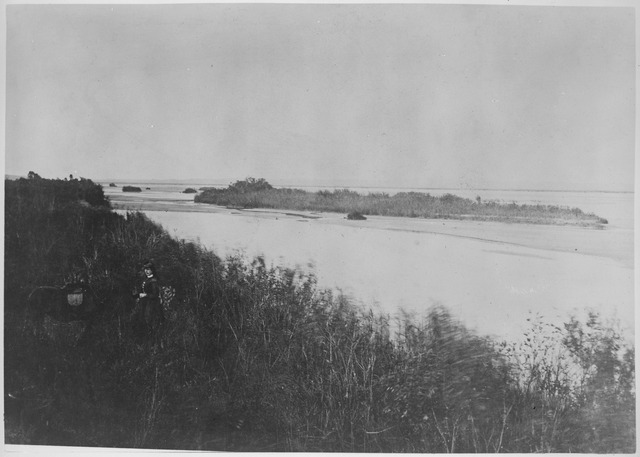

|

| Missouri River near Omaha Indian Agency, 1869 |

Wrapping up. There is so much more packed into this novel,

it’s hard to stop writing about it. Let it be said that it’s an absorbing

account of a troubled chapter in the lives of two men who are remembered as

national heroes. It’s a reminder of how historical fact defies myth, while

demonstrating that behind the myth are living, breathing human beings with much

to praise in them despite their faults.

Eclipse is currently available at amazon and

Barnes&Noble and for kindle and the nook.

Interview

Richard Wheeler has generously agreed to spend some time here at BITS to talk about writing and the writing of his novel Eclipse. Here are his comments on the imaginative task of telling the story of Lewis and Clark and bringing the two men to life on the page.

|

| Richard S. Wheeler |

Richard, talk about how the idea for Eclipse suggested itself to you.

In the 90s, a doctor who

lectured on the medicine of the Lewis and Clark expedition told me he had read

that Lewis had contracted syphilis, and it affected Lewis the rest of his brief

life. The doctor couldn’t remember where he had seen it. I sensed a novel, and

began a feverish hunt for the source, and after some serious looking over

several months, I found it.

An epidemiologist named Reimert

T. Ravenholt had examined the journals and concluded that Lewis had contracted

syphilis when the corps was staying with the Shoshones. Syphilis is a New World

disease, and Europeans were more vulnerable to it than native people. (Columbus

took it back to Europe, where it eventually killed a third of the people. It

was called the pox.)

Did the story come to you all

at once or was that a more complex part of the process?

I was fascinated by the swift

decline of Lewis, and the steady ascent of Clark after they got back. I

envisioned a novel that would be nothing more than the dramatizing of all that.

The expedition itself had been covered exhaustively in fiction and nonfiction,

and more was being prepared for the bicentennial by gifted historians, but it

seemed likely that a novel about the aftermath would have legs, and it did. I

was helped by the enormous literature. There was so much I finally tapered off

the research; I was writing a novel, not a new history.

Did anything about the story

or characters surprise you as you were writing?

When an historical novelist is

very lucky, he is overwhelmed with a sense of getting it right. That’s how this

evolved. As I wrote, I was occasionally filled with that euphoric sense of

capturing the period. Getting it down more or less as it happened. This was

especially true when I thought I had caught an attitude or prejudice that lay

deep within the character.

What parts of the novel gave

you the most pleasure to write?

Medicine of the period became a

fascinating subtext, crucial to the telling of the story. I immersed myself in

it, got help from doctors, learned as much as I could about diagnosis,

remedies, and also attitudes and nonscientific beliefs. (Such as the idea that

malaria rose from the “miasma” found in swamps.) Medicine governed my novel. I

learned what remedies got the expedition through three years of wilderness

travel. Native American medicine played a crucial role, too.

Did any parts of the writing

present a particular challenge?

The relationship of Clark and

his slave York was painful and difficult to depict. York was William Clark’s

boyhood playmate—and then slave. And then virtual freeman on the expedition,

and then slave again, with both men deeply antagonized. I wrote and rewrote all

that.

How much consideration did

you give to recreating the vernacular of the day?

The entire novel was narrated in

the language of the landed gentry of Virginia in the Federal period. I immersed

myself in it, both the formal and informal. The public documents of the

Founders were readily available, but the everyday speech, along with its

unspoken assumptions and habits of mind, was elusive.

There was also a need to depict

frontier and fur trade vernacular, which I absorbed through research. Once I

mastered Virginia’s way of speaking, I even began to think in it, to fashion

sentences as if they were wrought by Jefferson or Madison.

What went into the decision

to tell the story in the first person?

I depicted two very different men,

each with a lively private sensibility that didn’t always match his public

utterances. First-person is a novelist’s delight because it permits us to

follow the character’s inner convictions, motives, and secrets—and to depict

the darker and more hostile thoughts that would not otherwise see daylight.

Lewis was a very bright light,

and disease eclipsed it. The light of the foremost national hero of the time

was extinguished only three years later. It needed a subtitle, though, to make

it clear to readers.

What have been the most

interesting reactions of readers of the novel?

There was, maybe still is, a

sort of Lewis and Clark Establishment, with its own journal. It is devoted to

polishing the escutcheon of its heroes. Its magazine reviewed my book dourly,

plainly unhappy with my depiction of Lewis and his fate. But an odd thing

happened in the succeeding years. That Lewis contracted syphilis on the trip is

now the established version of events, as far as I can tell. Historians who

scorned the idea are now open to it.

There has always been

controversy about Lewis’s death—murder or suicide? Recently two young

historians published a work flatly stating that it was murder, done by the

family that ran Grinder’s Stand, where it all played out. They make a

compelling case, according to the reviews.

The descendents of Lewis are

open to exhuming his bones, which would give us multiple clues, but the

National Park Service forbids it. If the bones were loaded with mercury, for

instance, that would be evidence of dosing for syphilis. The trajectory of the

ball that entered Lewis’s skull might reveal much.

What are you reading now?

I just finished Loren Estleman’s

splendid historical novel, The Confessions of Al Capone.

What can your readers expect

from you next?

I’m starting on an historical

novel about an early vaudeville troupe touring 1880s Montana mining towns, such

as Helena and Butte.

Anything we didn’t cover

you’d like to comment on?

I want to thank you for your

truly remarkable and penetrating review of

the novel. You went straight to

the heart of my work, and I marveled as

I read it.

Thanks, Richard. Every success.

Further reading: BITS reviews of other

novels by Richard Wheeler

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

Coming up: Guy Vanderhaeghe, The Last Crossing

Fascinating. They have always interested in me and this review and interview spark my interest even more.

ReplyDeleteThe Ken Burns documentary piqued my interest, and seeing it again recently I noted that it's only a superficial treatment of a complex story.

DeleteThanks for this review and interview. I'm always interested in reading about the fiction of Richard Wheeler.

ReplyDeleteA couple more reviews are coming: BADLANDS and SIERRA.

DeleteDisease tears things apart, whether physical or mental. In the end it comes down to that it seems.

ReplyDeleteDisease overlaid with shame is the more thoroughly destructive.

DeleteEnjoyed Mr. Wheeler's observation about his research and "writing a novel, not a new history." Tricky to draw the line at the right juncture

ReplyDeleteHaving tried it myself, I can concur totally.

DeleteI have read six or seven of Mr. Wheeler’s novels and enjoyed them all. This one seems especially interesting to this old western history teacher. I will have this one on my Kindle by the end of the day. Thanks for pointing me toward another good read.

ReplyDeleteRon and all my colleagues in the field of western literature, thank you so much for the review and commentary. You people are the authorities and scholars of the West, and it pleases me that my work passed muster.

ReplyDeleteI have read this book three times and each time I come away with some new insight in the expedition. I have been collecting Mr Wheeler's book over many years and find his writing clever, informative, and factual, his is a great talent. I feel his Mr Skye series a good read with incites of truth about those time interesting. My thanks to him.

ReplyDelete