Myth vs. reality. Mulford has a reputation for historical accuracy. Tuska and Piekarski, in the Encyclopedia of Western and Frontier Literature make note of his “vast library” of sources. But a reader gets the feeling in this novel that Mulford is relying a lot on guesswork and dubious assumptions.

I said yesterday that he was born in Illinois, which is true, but he seems to have grown up in Brooklyn, NY. Many western writers born elsewhere who fell in love with the West eventually settled there. But Mulford didn't visit the West until he was 41 years old. Then he moved even farther away, living the rest of his life in Maine.

I said yesterday that he was born in Illinois, which is true, but he seems to have grown up in Brooklyn, NY. Many western writers born elsewhere who fell in love with the West eventually settled there. But Mulford didn't visit the West until he was 41 years old. Then he moved even farther away, living the rest of his life in Maine.

In Bar-20 he provides an accurate description of a spring roundup and how calves are branded. He explains the work of riding the line and the purpose of line cabins. He has Hopalong lecture a female companion on the many uses of mesquite. But he doesn’t relay much of the real work of cowboying.

His cowboys go into town to hang out in the saloon about every night. They have long vacations that permit them to roam like knights errant around the Southwest and into Mexico. On leave like this, they might try a hand at mining for gold. As a fraternity of mostly young males, they resemble a kind of Animal House in boots and chaps.

The outfits on the far-flung ranches, we learn, communicate with each other by smoke signals. There’s always a first time to run across a little known historical fact, but I have my doubts about the accuracy of this one.

What Mulford did understand was the ethos of the West. This is a long quote, from chapter 4, but what he says about the mythic West is right on the money:

A man was only a man when he had the qualities necessary; and the illiterate who could ride and shoot and live to himself was far more esteemed than the educated who could not do those things. The more a man depends upon himself and the closer is his contact to a quick judgment the more laconic and even-poised he becomes. And the knowledge that he is himself a judge tends to create caution and judgment. He has no court to uphold his honor and to offer him protection, so he must be quick to protect himself and to maintain his own standing.

His nature saved him, or it executed; and the range absolved him of all unpaid penalties of a careless past. He became a man born again and he took up his burden, the exactions of a new environment, and he lived as long as those actions gave him the right to live. He must tolerate no restrictions of his natural rights, and he must not restrict; for the one would proclaim him a coward, the other a bully, and both received short shrifts in the land of the self-protected. The basic law of nature is the survival of the fittest.

There’s a direct line between Mulford’s words here and the men who walked the pages of westerns during the century that followed.

Mulford and Wister. Tuska and Piekarski report that Mulford fell under the spell of Wister’s The Virginian when it was published in 1902. That novel has some of the same structural idiosyncrasies as Bar-20, as both writers incorporate earlier stand-alone pieces that don’t fit the narrative flow very well.

Wister had broader ambitions, however. He set out to explore the nature of character and to create a living example of its higher qualities. Though he has a checkered background and no education, the Virginian grows into a responsible member of society. His courtship and marriage to Molly are part of that process.

Trampas, Steve, and other men in the novel fall short of that ideal, and you can see Wister puzzling over how some men fail to make the grade. In the novel’s dedication to then-president Teddy Roosevelt, Wister offers the Virginian as an example of a new American hero, an uncorruptable man whose morality springs from his natural surroundings.

Mulford doesn’t have anything like this on his mind at all. Hopalong and his cowboy companions seem inspired by the horseplay, gambling, and drinking in the early chapters of Wister’s novel. By contrast, as the Virginian takes on new responsibilities at the ranch and rises to foreman, the foolishness comes to an end.

As for gunplay, shortly after the novel's beginning, the Virginian flashes a pistol in the famous card-playing scene with Trampas, but he doesn’t use it until the duel between them at the end. Mulford’s cowboys are forever joshing and joking, and it would take an ordinance plant working round the clock to keep them supplied with ammunition.

As for gunplay, shortly after the novel's beginning, the Virginian flashes a pistol in the famous card-playing scene with Trampas, but he doesn’t use it until the duel between them at the end. Mulford’s cowboys are forever joshing and joking, and it would take an ordinance plant working round the clock to keep them supplied with ammunition.

Wister wants to address the issue of vigilante violence on the range and attempts to justify the lynching of horse thieves without benefit of trial. This part of the novel is complicated further by the hanging of his friend Steve, which the Virginian does nothing to prevent. It’s a key moment in the novel that haunts the young cowboy long afterward. (William S. Hart observed that Wister lacked a basic understanding of the Code of the West. No true cowboy would have betrayed a friend like this, even if he was a horse thief.)

Mulford’s intent is way different. The action is what interests him, and the violence is there to ramp up the excitement. When his cowboys go after the cattle rustlers, the grand scale of the attack on their stronghold could have been inspired by the siege of the Alamo. Reading these chapters you can hear the distant hoofbeats of the B-western coming just over the horizon.

Despite the body count at the end of scenes like this, Mulford has one thing in common with Wister. Neither of them portrays the actual hangings of the thieves. When lynchings were still a fairly common practice in some states, it’s possible that both writers yielded to a degree of delicacy on the subject. But I could be wrong.

Mulford and Wolfville. There’s a tongue-in-cheek tone often in Mulford’s storytelling style that calls Alfred Henry Lewis to mind. It’s often used to make light of a high-risk situation. In an exchange of gunfire with an adversary named Travennes, Hopalong makes this observation:

Never before had Mr. Cassidy looked with reproach upon his .45-caliber Colt’s, and he sighed as he used it to notify Mr. Travennes that arbitration was not to be considered, which that person endorsed, said endorsement passing so close to Mr. Cassidy’s ear that he felt the breeze made by it.

The formalized sentence construction, like something from a legal contract, is heightened with the exaggerated courtesy of referring to each of the men as “Mr.”

Hopalong himself. Having grown up with William Boyd’s Hoppy, I have to put a truckload of preconceptions on hold as I read Mulford. The original Hopalong Cassidy is far from the fair-minded, good-humored cowboy hero for boys and girls that Boyd made him into. Mulford describes him as

a combination of irresponsibility, humor, good nature, love of fighting, and nonchalance when face-to-face with danger. His most prominent attribute was that of always getting into trouble without any intention of so doing.

He’s like Peter Pan, but with six-guns. It would be fun today to see a young actor play the red-haired, cussing, drinking puncher with a limp that Mulford created.

The good humor and his marksmanship with a six-shooter are the only points of connection between Hopalong and Hoppy. Hoppy’s good humor, in fact, is the surprising element of his character. He can get tough when he has to, but he’s always ready to have a good laugh at something funny. Ha-ha-ha.

It’s been an adventure scouring the Internet for pics of Hopalong that don’t bear a resemblance to William Boyd. I’ve included them on this page to show how he’s evolved graphically over the past 100 years.

The illustration of Hopalong in the hayloft door at the top of the page in fact dates from the publication of the story “The Fight at Buckskin,” which opens the novel. It appeared in the December 1905 issue of Outing Magazine. It’s a rough-looking guy who hardly looks like a youth. This same image appears on the cover of the novel, published the next year.

An early dust jacket shows a hatless Hopalong behind a boulder with a smoking gun, which is straight from a scene in the book, where the three-days growth of beard reflects the time he’s been on the trail of horse thieves. His hat has been lost, already shot from his head in the gun battle.

The dust jacket for Bar-20 Days (1911) with two cowboys is the work of Maynard Dixon. Here the men look suitably younger and more handsomely dressed. It may be meant to represent Hopalong and his buddy Red Connors.

Jump ahead to the late 1930s, and there’s the cover of one of Mulford’s last novels, Hopalong Cassidy Takes Cards (1937). Smoke from his revolver drifts through his dark and not-so-red hair, while his high-crown Stetson falls behind him, a bullet hole in the top of it. The edition of the novel from the 1940s shows him with two smoking revolvers, a bright red shirt, and his hat firmly in place. In the foreground are the legs, akimbo, of what must have been a crooked dealer.

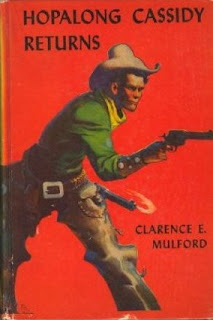

It’s hard to judge some of these, but by the lettering, I’d call the dust jackets for Hopalong Cassidy Returns (1925) and Hopalong Cassidy’s Bar-20 Rides Again (1926) as editions dating from around 1950.

Jump ahead once more to paperback editions of the 1990s, and the man from the Bar-20 has a whole new look. The cover of The Man From Bar-20 (above) shows a guy who gets around in a late model Ford pickup with a gun rack and subscribes to Field and Stream.

Meanwhile, the cover of Bar-20 Days (at right) gives him a denim shirt and leather vest, with a red neckerchief and even a mustache. He looks directly out from the illustration, not caught in the middle of exciting action but reflective. In fact, he looks like a model at a photo shoot for a Marlboro ad. We’ve come a long way from that scruffy hellion perched with a rifle in the doorway of a hayloft.

Further reading:

Jon Tuska, "The Coming of Cassidy," The Filming of the West, Doubleday: New York, 1976, pp. 312-323.

Picture credits:

1) Hopalong Takes Command, 1905, from “The Fight at Buckskin,” by Clarence Edward Mulford, in Outing Magazine, December 1905, by Frank Earle Schoonover (1877-1972), commons.wikimedia.org

2) Book cover: Bar-20, manybooks.com

3) Dust jacket: Bar-20, sherlockiana.dk

4) Dust jacket: Bar-20 Days, Maynard Dixon,1910, maynarddixon.com

5) Book covers: Hopalong Cassidy Takes Cards, fantasticfiction.com; 1948 paperback, coverbrowser.com

6) Dust jacket: Hopalong Cassidy Returns, amazon.com

7) Dust jacket: Hopalong Cassidy’s Bar-20 Rides Again, fantasticfiction.co.uk

8) Book cover: The Man From Bar-20, fantasticfiction.co.uk

9) Book cover: Bar-20 Days, fantasticfiction.co.uk

Coming up: Review of B. M. Bower's Chip of the Flying U

Wow, you've done some yeoman's work on this series. This deserves a wide audience. Surely a book about the pulps would want this.

ReplyDeleteCharles, thanks. I'm still kind of finding myself with this material, and shooting from the hip. Eventually, it should turn into something.

ReplyDeleteRon, you have found yourself. I highly recommend a book on all this research. You have an audience waiting.

ReplyDelete