According to the writers, black cowboys were typically skilled at breaking horses. Many also worked as cooks on the trail, one of whom is profiled in the book. In general, a black member of an outfit was expected to do the work that the white men preferred not to. John Hendrix, writing in 1936, is quoted in the book as saying:

This most often took the form of “topping,” or taking the first pitch out of the rough horses of the outfit as they stood saddled, with back humped, in the chill of the morning, while the boys ate their breakfast . . . It was the negro hand who usually tried out the swimming water when a trailing herd came to a swollen stream or if a fighting bull or steer was to be handled, he knew without being told it was his job (p. 194).

The men who are remembered were also top-notch riders and ropers. Their stories were often recorded because they were favorites of their white employers.

Color. This favoritism figured into the way they were accepted by white cowboys and others. It has been said that race relations on the trail were somewhat relaxed, but the evidence shows otherwise. A black man could be a trail boss only for other black cowboys. White cowboys would not take orders from him.

Color could prevent him from being served at a bar in a cow town. He might be challenged to a fight by another cowboy who objected to his taking an “inappropriate” liberty. He’d have to duck out of a confrontation, unless he was good with his fists or fast with a gun. Even then, he’d want a white boss or the white cowboys of his outfit for backup.

The black cowboys we meet in this section tend to be loners. Partly accepted by others in the outfit, they might not identify with other blacks or even associate with them. Of these, many had their closest personal ties to the owner, who relied on them as trusted companions. This may well be a hangover from slavery days, which had officially ended only a handful of years previous.

Cattleman Charles Goodnight had such a man in Bose Ikard, a mixed-race son of a Mississippi plantation owner. Ikard, at age 19, joined 30-year-old Goodnight in 1866 on a cattle drive along the Goodnight-Loving trail into New Mexico. Like many black cowboys at this time, Ikard had developed his skills tending the cattle and horses during his ranch owner’s service in the Confederate Army.

Goodnight never forgot Ikard. He had a monument erected on his grave in Weatherford, Texas, after his death in 1929. The epitaph read:

Served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior. – C. Goodnight

Readers of Lonesome Dove may well be reminded of Woodrow F. Call’s similar epitaph on the grave marker for the trail drive’s black scout, Deets.

Addison Jones. As a result of their separate social status among whites, many black cowboys were never married. One of them, Addison Jones, cowboying in West Texas and New Mexico, found few black women to choose from. Here, where both whites and Hispanics objected to a mixed-race marriage, he did not find a spouse until age 54. His young wife, a rooming-house cook in Roswell, was 36.

Addison Jones, in fact, was commemorated in a lyric written by cowboy songwriter and collector Jack Thorpe (see more about him here). Jones was well known for his knowledge of brands. And in a song called “Whose Old Cow?” Thorpe wrote:

Well after each outfit had worked on the brand

There was only three head of them left

When Nig Add from LFD outfit rode in

A dictionary on earmarks an’ brands.

You’ll notice a form of the n-word in that simple verse. Probably little known by anyone today, the full form of the word was typically used as part of a black man’s name in the Old West.

James Kelly. My favorite chapter in this section of the book is the story of James Kelly. Born in 1839 of parents who were free blacks, Kelly was a big, fierce, and hard man who ran with a rough outfit. Teddy Blue Abbott (see We Pointed them North) who worked for his employer, Print Olive, remembered both men as tough customers.

Print and his brothers were cattlemen, quick to take violent action in defense of their interests. They once treated two rustlers to “cowhide killings,” a form of torture said to have been practiced by Spaniards. Both were wrapped in fresh cowhides, which then crushed them as they dried and contracted in the heat of the sun. [This form of punishment is the basis for a story “The Rawhide” in Arizona Nights (1907) by Stewart Edward White.]

Like the rest of Olive’s men, Kelly carried a gun and was encouraged to use it. Arming a black man would have been a notable act at the time. Ranches continued a practice from slave days of not permitting blacks to carry firearms. The exception to this were the trail drives, where:

Cowboys stored their rifles in the chuck wagon and carried their guns for protection from Indians and cattle thieves. They arrived at the end of the trail carrying their pistols (p. 107).

After a cattle drive to Kansas, Print Olive got into a disagreement over a card game and was shot three times before Kelly pulled his own gun and shot the assailant. After recovering and returning to Texas, Olive chose to relocate his ranching operation to Nebraska, and Kelly followed.

There Kelly acted as a “heavy” for his boss, terrorizing homesteaders trying to settle in the Olives’ open range. If they resisted, cattle would be run over their property and fences cut. In 1878, Olive, Kelly, and several other men eventually hanged two homesteaders believed to be killing Olive’s cattle. Kelly returned to Texas while Olive and another man spent a year in the Nebraska State Pen for the crime.

Kelly appears again in Teddy Blue Abbott’s book as both men accompanied another drive of Olive clan cattle northward. This time Print’s brother Ira got into a dispute with Kelly and shot him in the face, taking out two of his teeth. Kelly, out of loyalty to the rest of the family, did nothing, and Abbott claims to have come to his defense. Kelly lived to 1912 and is buried in the town cemetery at Ansley, Nebraska, in Custer County.

Wrapping up. I got a lot out of this book, including a reference to an Elmer Kelton book, Wagontongue, which apparently takes up white-black relations in a western setting. Some details about the extremities of weather conditions on the trail drives were also new.

At least two accounts describe blizzards so severe that horses died from the cold, some right out from under their riders. In once case, the cattle were allowed to drift, and the cowboys saved themselves from freezing by crawling into their sougans, sometimes more than one to a bedroll.

Among the stories told in the book, there are a few amusing ones, like this one:

Packing a pistol and shooting up the town of Abilene landed one African American cowboy in the town’s newly built stone jail, earning him the distinction of being the first prisoner of the jail and the first to break out when the trail crew busted him out of jail (p. 107).

You also get an appreciation for the WPA Project, which recorded oral history during the Depression years. Many recollections of former slaves during the post-emancipation decades were an invaluable resource for the compilers of this book.

A drawback of the book is the quality of the writing. Many of the profiles are written with only a modest competence at storytelling. There may have been too little to actually spin a narrative for some subjects. Often, the slender thread of a life story makes you think of how much has been lost. But the fragments of personal stories when taken together hint at a world that fiction could knit into compelling narratives.

Picture credits:

1) Cattle crossing the Smoky Hill River at Ellsworth, on the old Santa Fe crossing; photograph by A. Gardner, 1867; Library of Congress, wikimedia.org

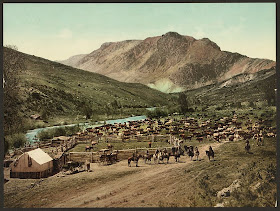

2) Round up on the Cimarron, Colorado, c1898, Library of Congress, wikimedia.org

3) A cattle round-up in Arizona, "cutting out" the cows and calves; Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views, wikimedia.org

4) Cattle round up; Distant of view of cowboys and cattle herds on the plains,1891; John C. H. Grabill Collection, Library of Congress, wikimedia.org

Coming up: J. Marvin Hunter The Trail Drivers of Texas

It seems we are left wondering just how much we owe to other races, for there efforts in creating the future.

ReplyDeleteThe first western I remember reading with a black cowboy was "All God's Chillun Got Guns," which did a nice job of playing off the expectations of the west. I wonder too whether the percentage of black cowboys differed in say Texas from Montana. I'm guessing so.

ReplyDeleteSomewhere I remember reading that there were two black cowboys who ran a ranch in the Caliente Nevada area.. Interesting posts.

ReplyDeleteCheyenne, they could probably tell us.

ReplyDeleteCharles, I'll look for that book; sounds interesting. I haven't come across numbers for Montana, but I'm guessing you are right. There were Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Belknap. Ivan Doig's novel PRAIRIE NOCTURNE touches on that subject.

Sage, I'm not surprised.