Born in Nebraska in 1892, Gibson reportedly left home at the age of 13 to join the circus. By 16, he had worked as a cowboy and as a performer in Wild West rodeo shows. In his early twenties, he began in movies as a stuntman and double. After returning from service in WWI, he had a career as a film star that ranked him for a while among the likes of Tom Mix.

In 1931, when Wild Horse was made, he was pushing 40 and a new army of younger talent was taking over the western – such as singing cowboy Gene Autry. With his own ranch and his own movie pals, Hoot kept on making movies, though he never really survived the transition to talkies.

Appearing along with Hoot in this film is the far more authentic cowboy-actor Skeeter Bill Robbins. More cowboy than actor, Robbins was the manager of Gibson’s ranch in Saugus, California. A head taller than Gibson and skinny as a pipe cleaner, Robbins looks even thinner next to the well-fed Gibson.

|

| Poster for King of the Rodeo (1929) |

The plot. Wild Horse is set at a ranch rodeo, with Hoot as a bronc rider. The wild horse of the title is a magnificent stallion called Devil worth $1000 to anyone who captures him. Gibson and Skeeter Bill do the capturing, but a jealous competitor, Gil Davis, steals the horse after killing Skeeter, and wins the money.

A bank robber figures into the story as witness to the murder. But when the sheriff arrives the evidence points, unfortunately, to Hoot, and he gets arrested for the death of his partner. “The best pal I ever had,” he says.

Out of jail again, he is trampled by the now-captured wild horse and hospitalized. After recovering, he successfully rides the horse before a cheering crowd. Then he captures the killer, who makes a confession when he is confronted with the truth by the robber, who has now been captured, too.

|

| Alberta Vaughn, 1924 |

Added value. There’s a girl in the plot (Alberta Vaughn) who gets a good share of screen time as she befriends Hoot. She’s a comfortable presence in the film, never called upon for much but to grace the mise en scene. A Hollywood veteran, she appeared in some 130 mostly short films from 1921 to 1935.

The shooting of the film is not exceptional, except there’s a dramatic fight scene between two horses that doesn’t look faked. In another scene, director and cameraman were inspired when setting up a shot in which Hoot stands in an open door, stunned at the discovery of his dead pal Skeeter. Behind him, framed by the doorway, a horse and rider silently appear on a hillside and slowly approach.

Rodeo footage and editing of the film capture the excitement of the rough stock events. One cowboy is thrown and carried from the arena on a stretcher. High-angle long shots show the rodeo grounds with grandstands, crowds – and rows of parked automobiles. With this last detail, the hard-ridin’, shoot-em-up frontier West gets mashed up with a story that takes place in the present.

|

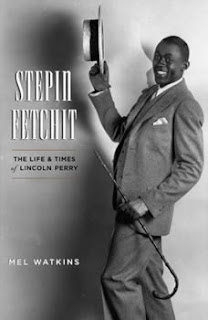

| Biography, Pantheon, 2005 |

In a way, the laugh was on the audience, for Fetchit (real name, Lincoln Perry) was anything but stupid. He portrays a character type that goes back to slavery days, playing dumb to outwit the white folks. In 1931 he was at the beginning of a career that would make him a millionaire. Unlike his screen persona, he was a literate man and a writer, though the excesses of his private life soon got him bad press, and he spent himself into bankruptcy.

|

| Will Rogers |

His first starring roles had come in 1929 with Hearts in Dixie and Show Boat. Later, in 1934-35, he starred with his friend Will Rogers in four of the Oklahoma cowboy humorist’s films. While the bulk of his 54-film career was over by 1940, he appeared in a scattering of movies in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

In this film, Fetchit struggles with a stubborn mule that has nothing to do with the plot. It’s an example of a task or chore he’s been asked to do, and he whines incomprehensibly as he fails to understand how to get it done or why he even needs to do it. Watch his scenes and then see if you’re able to say, “That’s entertainment!”

Which is unfortunate, because there’s a lot to commend this film. The DVD has been transferred from an above-average print for a B-western of this era. The screenplay was by another Nebraskan, Jack Natteford, a prolific Hollywood writer, with 150 movie and TV credits. Wild Horse was based on a story by western writer Peter B. Kyne, whose The Three Godfathers (1913) will be reviewed here soon.

By the way. Wild Horse is the last of the classic westerns I was lucky enough to win at Laurie Powers’ pulpwriter.com. It’s in a box set of DVDs that came from OutWest, Bobbi Jean and Jim Bell’s well-stocked online western store.

By the way. Wild Horse is the last of the classic westerns I was lucky enough to win at Laurie Powers’ pulpwriter.com. It’s in a box set of DVDs that came from OutWest, Bobbi Jean and Jim Bell’s well-stocked online western store.Further reading:

Picture credits: wikimedia.org

Coming up: A. M. Chisholm, Desert Conquest, or Precious Waters (1913)

A name I know but have never watched a film of his. Good history mixed with review, Ron.

ReplyDeleteGotta wince a bit at the Step and fetch it thing. I haven't seen this one. I don't imagine they run it on late night TV much

ReplyDeleteGreat review, Ron. Yes, those old movies did have their unfortunate stereotypes. But if we cut them out, it would make us just as guilty as the publisher who is replacing the "n" word in HUCKLEBERRY FINN and replacing it with "slave."

ReplyDeleteDavid, thanks. The historian in me is always duking it out with the reviewer.

ReplyDeleteCharles, it's a shock if you haven't seen the routine before.

Laurie, I've read that these scenes were typically cut when the movie was shown in later years. I give the distributors of this film credit for keeping it intact.

Ron, Wonderful review. I hope to get the opportunity to see this film.

ReplyDelete