The Brand takes its

title from a key moment in the novel’s closing chapters as Broderick’s feminist

message is burned permanently into the hide of its villain. But the novel’s

subtitle, A Tale of the Flathead Reservation, promises somewhat more than it delivers.

Full-blooded Indians are mostly peripheral to its story of a “quarter-breed’s”

forbidden love of a white woman.

Plot. Young Bess

Fletcher arrives by train in Montana with her brother Jim. They are on their

way to the cattle ranch of Jim’s college pal, Henry West, a fellow Harvard

graduate. The ranch is on the Flathead reservation close to Polson and Flathead

Lake. Jim, who has lived and worked on the ranch before, has been hired as

Henry’s foreman.

|

| Bess Fletcher |

The West is all new to 20-year-old Bess, who is enraptured

by its promise of “untrammeled freedom.” She will hear nothing, she says, of

“don’ts and can’ts.” However, a Big Don’t governs much of the plot of the

novel.

Henry West is a handsome man, well polished and a gentleman.

One look at Bess, and he recognizes her as the sweetheart he has long dreamed

of and yearned for. He is, alas, only three-quarters white and, for her, on the

wrong side of the color line.

Meanwhile, she is being courted by David Davis, the government

agent of the Flathead reservation. He is an oily and manipulative character,

entirely too pushy in his seductive advances. Henry despises Davis but has a

horrible secret involving the honor of his dead sister, Helen, which prevents

him from speaking up about the man. We gather that Davis was the contributing

cause of her death, though Broderick is not specific about the details.

Bess was schooled by convent nuns and is an innocent about

affairs of the heart. She feels no real affection for Davis but is too polite

to turn him away. In time, she persuades herself that he is the right man for

her. But on the day of their wedding, seeing Davis for the

first time, her bridesmaid recognizes him. He is the man who once seduced and abandoned

her sister—which brings an abrupt end to the ceremony.

|

| Indian farmer, Flathead Reservation, 1914 |

Character. An irony

in the novel is that Henry is as thoroughly schooled in matters of character

as any of the other men. Being an exemplary gentleman is as close as he can

come to being white. At first meeting, Bess finds him “splendid,” and Jim tells

her,

At college he was so superior in

mind, ability, and morals to the majority of his colleagues, that every one

looked up to him. He was one of them and no gathering was quite complete

without Henry West.

She says to her brother, “I had no idea there were such men

as he away out here in the West! No wonder you rave over him and always sing

his praises.

|

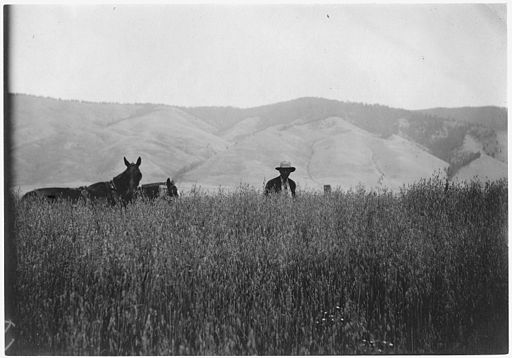

| Oats field, Flathead Reservation, 1912 |

Villainy. Davis (or

Davies as he is revealed at the end) is first and last a cad. If he is guilty

of the usual corruption ascribed to government agents of Indian reservations,

we get no hint of it. But we gather that he freely takes liberties with the

native women. We get a sample of this when Bess has playfully dressed and made herself up

as a squaw, and he mistakes her for an Indian. Altogether, he is a lesson in

the employment of seductive maneuvers to weaken a woman’s resistance.

Even revealed at last for his truly evil self, he is

fiercely unrepentant. We see the full extent of his cunning when he returns to

take Bess by force. She has to pull a revolver on him to defend herself. He

doesn’t relent until Henry drags him to the branding fires where the ranch’s

brand “HW” is burned into his chest. That means “Honor Women,” Henry tells him.

|

| Haying, Flathead Reservation, 1914 |

East vs. West. The

novel voices the usual commonplaces about the superiority of life in the West.

Returning from the East after two years, James is pale and sickly. He begins to

recover his health as soon as he’s riding a horse and working in the open air.

Bess’s easy abandonment of Eastern ways starts with riding

astride her horse instead of side saddle. Given a rifle to practice target

shooting, she proves herself a master in three weeks’ time and is given a .38

Smith & Wesson to carry. She uses it to kill a rattler and then has the

temerity to wear the rattles on her hatband.

Style. This is a

readable novel with a story told at a reasonable pace. The protracted courtship

of Bess by the villain Davis makes for some skin-crawling scenes, as time after

time she allows him to get over-familiar. You wish someone had told her that

etiquette doesn’t require her to be polite to men with boundary issues.

|

| Alex Matt, Flathead Reservation, c1890 |

There are page-turning scenes of suspense, as when Broderick

gets her heroine lost, separates her from her horse, and puts her in the path

of a stampede. This requires a rescue by Henry, whose horse is exhausted by the

ordeal and has to be shot. Somewhat more original are her passages of realistic

description, for Broderick seems to be familiar with the area where her story

takes place.

Wrapping up. Broderick’s

dates are unknown. The Brand was published by Alice Harriman in

Seattle, and it seems to be Broderick’s only published work. She is chiefly

remembered today for inspiring the novel Cogewea, The Half-Blood (1927) by Native American writer, Mourning Dove

(Christal Quintasket).

The Brand is

currently available online at google books and Internet Archive, and for the nook. For more of Friday’s Forgotten Books, click over to Patti Abbott’s blog.

Image credits:

Illustration from the novel by an unknown illustrator

Photos, Wikimedia Commons

Sources:

Nina Baym, Women Writers of

the American West, 1833-1927, 2011

Coming up: Saturday music, Patti Page

I've read quite a few stories where the sickly civilized fellow becomes a man's man after being thrown into, or back into, the wild. ERB did quite a lot with that theme.

ReplyDeleteLiving in the west I like the East v. West stuff. Come west and regain your health.

ReplyDeleteI see you have Holt County Law in your queue, I just download it myself, I was born in Holt County as was my dad and his dad, looking forward to starting it this evening.

You would think that Davis/Davies feller would learn his lesson after a couple attempts at seducing Bess. I hope the branding finally made him a believer.

ReplyDeleteRon, I find the East vs. West comparison interesting. If the wild west, as we know it, was to the west of the Mississippi River, how different was life to the east of the river? By Bess's "easy abandonment of Eastern ways" by sitting astride her horse, as opposed to sitting side-saddle, the women in the east, I gather, were more cultured with refined tastes and manners, as were the men probably, to put it mildly. The use of firearm in the west, I think, is another fascinating analogy of the differences between the two regions.

ReplyDeleteI liked the cover of this book and I can picture it as a hardback.

Prashant, in popular fiction, the West allows for greater freedoms of all kinds. Socially it is more egalitarian, and economically there is greater opportunity. Someone with poor prospects or whose life has derailed can go west to "start over," even to "reinvent" themselves (a notion that still holds true to some extent today). The climate was also considered more healthful, its distance from urban crowding and the comparative aridity a boon for people with TB and other pulmonary problems.

DeletePeople in the west still craved urban amenities and were aware of fashion trends. You read of the widespread reading of magazines (often passed on from hand to hand) and the demand for books. Traveling theatrical companies, lecturers, etc. filled frontier "opera houses." But the social refinements attending these cultural events back East would be less evident in the West.

The common use of firearms dates from the general absence of "the law" during the earliest days of settlement. People had to rely on themselves for protection against outlaws, thieves, natives, and animal predators, but there was also a "code" governing gun use. Stealing horses and cattle was a capital crime, so was a killing that was not in self-defense.

Ron, thanks very much for taking the trouble to explain some of the economical, social, and cultural differences between the East and West. I never thought of the West as egalitarian or one that offered greater opportunity or a place where someone could go to for a fresh start in life. You have cited some fine examples of the division between the two regions, particularly the health angle. That sort of thing used to happen in India too where urban dwellers would go to the countryside for a rest-cure, often to recuperate from TB. Over the past 20 years, greater opportunity has been attracting vast numbers of the rural populace to the cities and big towns for the same reasons that you mention, to "start over" and "reinvent" themselves. I suppose this has been, and still is, a universal trend. In this context, Indians continue to emigrate to the West, the land of opportunity.

Delete