|

| Montana cowboys, c1910 |

Here’s another set of terms and forgotten people gleaned

from early western fiction. Definitions were discovered in various online

dictionaries, as well as searches in

Cassell’s Dictionary of Slang,

Dictionary of the American West, The New Encyclopedia of the American West, The

Cowboy Dictionary, The Cowboy Encyclopedia, Vocabulario Vaquero, I Hear America

Talking, Cowboy Lingo, and The

Shorter Oxford English Dictionary.

These are from Alice Harriman’s A Man of Two Countries, a political drama set in early Montana, and Agnes

Laut’s The Freebooters of the Wilderness, about theft of public lands in the West. Once again, I struck out on

a few. If anyone has a definition for “the jigs,” “rastical,” “copper gentry,”

“full pelther,” “sternwheeler hat,” “chack up,” or “tum-jack,” leave a comment

below.

bally = an intensifier; cf. bloody. “Don’t be a bally fool

and buck into a buzz-saw!” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

blind pig =

an unlicensed drinking house. “You make

the Senator’s job and your job and public service all round a bunco game, a

bunco game with marked cards; while we Service and Land fellows act the decent

sign for a blind pig.” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

buffer = a fool. “Every bar-room buffer in the country side

will know it by night.” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

by Harry =

a mild expletive. “‘By Harry,’ cried

Wayland, ‘that mule does smell water.’” Agnes C. Laut, The

Freebooters of the Wilderness.

cartwheel hat =

a woman’s hat with a low crown and a wide

stiff brim. “Eleanor took a quick glance at her neighbors, all men but the

cart-wheel-hat to one side and a little young-old lady opposite.” Agnes C.

Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

catspaw = a person used as a tool by another. “Be sure that

she is promised something she thinks worth her while, by Bob or by Moore, for

her sudden interest in politics and—Charlie Blair. She is a good catspaw.”

Alice Harriman, A Man of Two Countries.

choke off =

to silence or get rid of someone, stop a

person’s activities. “Choke it off! He’s staying with Missionary Williams at

the Indian School, and you know about how much love is lost between Williams

and Moyese.” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

clockwork =

embroidery or woven work on the side of

stockings. “She raised her eye lashes and looked the speaker over from the

undertaker’s plumes and the gold teeth and the ash colored V of skin to the

clock-work stockings and high heeled slippers.” Agnes C. Laut, The

Freebooters of the Wilderness.

congé = dismissal, permission to depart. “Father will be

furious when he knows that I’ve given Mr. Burroughs his congé.” Alice Harriman,

A Man of Two Countries.

dee-fool =

damn fool. “One of the first things Moyese

told me when I went on his paper was never to monkey with the dee-fool who

wastes time justifying himself.” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the

Wilderness.

entryman =

one who enters upon public land with

intent to secure an allotment under homestead, mining, or other laws. “I didn’t

know Senator had his drag net out for parsons as dummy entrymen!” Agnes C.

Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

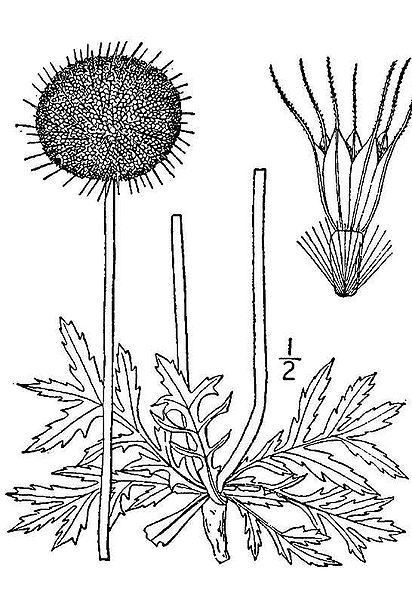

|

| Everlasting pea |

everlasting =

flowers or foliage that retains form or

color for a long time when dried. “It was the Ranger in his sage green Service

suit wearing a sprig of everlasting in his Alpine hat.” Agnes C. Laut, The

Freebooters of the Wilderness.

floater = a writer who travels to gather and write up often

erroneous impressions. “Bat’s floater was working for a Chicago boomster, who

had issued a magazine to boom Western real estate.” Agnes C. Laut, The

Freebooters of the Wilderness.

frap = to strike, beat. “The old frontiersman literally

avalanched off his broncho and made a dash at the tent flap, frapping it loudly

with the flat of his hand.” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the

Wilderness.

frontier knock =

a scratching sound made on the flap of a

tent. “She had heard the unmistakable voice of Mr. Moore. Had he used that

frontier knock?” Alice Harriman, A Man of Two Countries.

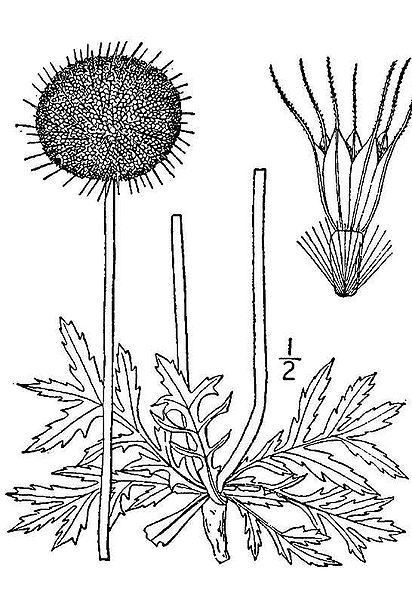

|

| Gaillardia suavis |

gaillardia =

an American flower of the daisy family,

cultivated for its bright red and yellow flowers. “The gold of yellow midsummer

light dyed in the asters and sunflowers and great flowered gaillardias and

golden rod, with an odor of dried grasses or mint or cloves.” Agnes C. Laut, The

Freebooters of the Wilderness.

ghost walker =

a person who feigns or fabricates an

assignment. “ ‘High brows,’ ‘dreamers’ ‘ghost walkers,’ ‘barkers,’ ‘biters,’

‘muck-rakers!’ Oh, he knew the choice names that lawless greed cast at such as

he.” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

gird at = to jeer or jibe. “‘N-o,’ hesitated the lawyer,

divided between a desire to gird at the doctor, or to soothe his civic pride.”

Alice Harriman, A Man of Two Countries.

headlights =

false or capped teeth. “The gold

headlights suffered eclipse behind a pair of tightly perked lips.” Agnes C.

Laut, The Freebooters of the Wilderness.

job = to turn a public office or position of trust to

personal advantage. “Fight for all the fellows in the Land and Forest Service

when they see a steal being sneaked and jobbed!” Agnes C. Laut, The

Freebooters of the Wilderness.

jug through =

to deceive, either jokingly and through

some illegality. “He stole ’em, those coal lands. He jugged ’em thro’ Land

Office records with false entries.” Agnes C. Laut, The Freebooters of the

Wilderness.

_Peace_Commissioners._L_to_R,_Chas._Bassett,_W._H._Harris,_Wyatt_Earp,_Luke_Short,_L._McLean,_Bat_Mas_-_NARA_-_530990.jpg/482px-%22Dodge_City_(Kans.)_Peace_Commissioners._L_to_R,_Chas._Bassett,_W._H._Harris,_Wyatt_Earp,_Luke_Short,_L._McLean,_Bat_Mas_-_NARA_-_530990.jpg)