Some readers

here will know James Wood as a book reviewer (he would say critic, I suppose),

at The New Yorker. Published in 2008,

this book suggests by its title that it’s a how-to manual for writers, but it’s

better described as a what-to-notice for readers.

Wood covers a

half dozen or so topics: narration, point of view, detail, character, and realism.

In his preface, he states that his argument is that fiction is both “artifice

and verisimilitude.” In other words, it draws on a store of conventions and

fakery to create an illusion of reality.

Detail. This assertion won’t come as a surprise to many readers or writers.

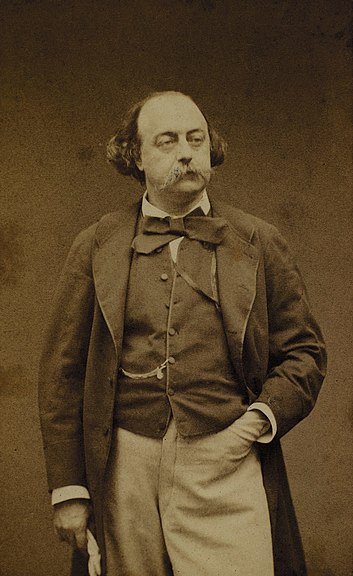

What’s interesting about Wood’s argument are the examples he uses, starting with

Flaubert, whom he credits with virtually inventing the modern novel, with its

eye for concrete detail. Whether in literary or genre fiction, the prominence

given to visual, audio, and other sensory images becomes suddenly obvious after

Wood points it out. You see that it is part of the artifice.

|

| Gustav Flaubert |

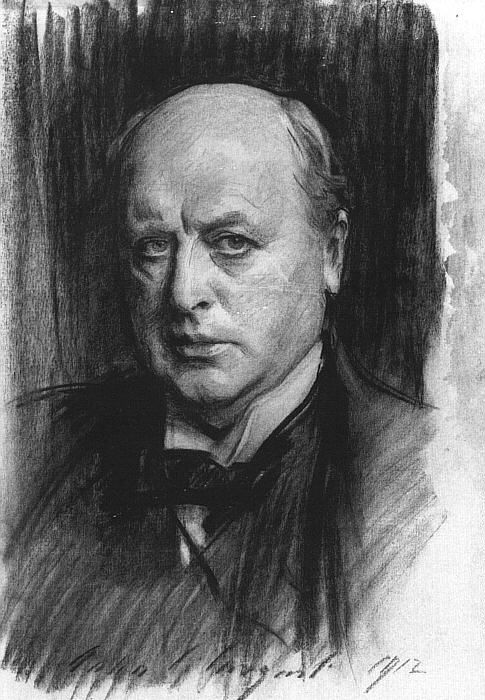

Narration. More complex is the matter of narration. Wood

argues that all narration is unreliable, and third-person more so than

first-person. To demonstrate this last assertion, he takes apart a paragraph

from Henry James’ What Maisie Knew.

There he finds a supposedly unbiased and neutral narrator using a word betraying

an attitude that Maisie would not herself possess.

It’s a

surprising revelation when you realize how writers do this all the time,

blurring the line between the storyteller and the character—sometimes for a

clever sleight-of-hand effect, sometimes from lack of narrative precision.

Wood has a term

for this: free indirect style. The point of view is located close to the conscious

awareness of a character, but the narrator may be using language and reporting

details that would not match the character’s own vocabulary or

perceptions.

Story. Disappointing for me was Wood’s choosing not to discuss very deeply another aspect of the subject: how story works. What is it that grabs

and holds one’s interest over the course of a story? While it may have

character and plot, what is happening when a story fails to do this for us?

|

| Henry James |

Far more

interesting are the moments when a story finds traction and takes off,

absorbing my attention. If I have awareness of it at all, I’m wondering, “Now, how

did that happen?”

Wrapping up. I’m ending today

with two TED talks on the subject of storytelling. One is by a literary agent

Julian Friedmann. The other is by screenwriter and filmmaker Andrew Stanton (Toy Story, WALL-E, Finding Nemo). The two

make good points and mostly agree, except on an often cited piece of advice. One says to draw from life; the other says not to, because life is boring.

Friedmann makes

an observation that as a reader I would encourage fiction writers to give more thought

to—allowing the audience to be more actively involved in the creation of the

story. That means leaving blanks for them to fill in, and not over-explaining, making all the connections, or clearing up ambiguities. The audience is already hardwired to

do that. Best to remember: less is more.

|

| Aristotle |

The audience is

thus the true inventor of the story, not the writer. We use stories to look at ourselves

and to rehearse our fears. And Friedmann credits Aristotle for discovering

this. A good story makes an emotional connection between character and audience,

and the process is simple: we feel pity for the character as they

suffer adversity; we feel fear as their situation worsens and

they struggle to regain control; and we feel catharsis when they

finally overcome.

His argument

may be a bit self-serving but Friedmann makes a point that deserves consideration.

People like himself (that is, agents, editors) are not gatekeepers with the ability to select the fortunate few for fame and fortune. Only an audience can do that.

Finally, here is

Andrew Stanton, telling his own story as a writer. While Friedmann offers more

pragmatic advice and makes interesting comparisons between British and American

films, Stanton makes a moving point about how the film Lawrence of Arabia made an emotional connection for him as a young

moviegoer. [Caveat: His talk begins with a funny story that some here may find off-color.]

Coming up: Broncho Billy and the Greaser (1914)

Terrific post, Ron.

ReplyDeleteFor me, the heart of fiction is dilemma. Some argue that it is conflict, but I can write a powerful story with no conflict at all, carried by dilemma.

ReplyDeleteI think of dilemma as inner conflict, and I agree that it can really carry a compelling story.

DeleteThe Lady and the Tiger (if I am remembering correctly): open one door and she's free. Open the other door, and she's meat for the tiger. Dilemma, and not resolved at the end of the story.

DeleteGood one. I hadn't thought of that.

DeleteGood review. Thanks. Here's Kurt Vonnegut on storytelling.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oP3c1h8v2ZQ

Wonderful. Thanks for the link.

DeleteRon - Fantastic post. Your comment about being "grabbed" as a reader made me stop and think: Isn't every reader, lover of fiction grabbed by something unique to her or his mind-set? A beloved aunt of mine told me years ago to watch Gone With the Wind every ten years, that it would have a different impact on me each time.

ReplyDeleteWonderful to watch and hear Andrew Stanton's take on all this. Thanks, kcf

I'm aware of this in myself as "identification." A character is dealing with something that hits close to home for me (or not, as the case may be).

Deletethe idea that all narration is unreliable is fascinating. I hadn't really thought of that and will have to study on the possible meanings of that one.

ReplyDeleteThis fascinated me, too. Wood made me see how the trust we put in a third-person narrator is often unwarranted.

DeleteThere are many books where I like third person narration, although it can be too descriptive leaving not enough to the readers imagination. If its well written I think it works.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Ron. This post came just at the right time for me.

ReplyDeleteMr. Gramlich's comment is also my own. Interesting food for thought.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Ron. I hope I've learned something from the movies and your fine post.

ReplyDeleteOrdered How Fiction Works from the public library - one copy in our north Idaho region. Looking forward to reading it. Thanks, Ron.

ReplyDelete