When a colleague offered to make me one of his famous-person

portraits as a retirement gift, he was already prepared for me to pick Randolph

Scott as a subject. The two of us had spoken often of Scott’s cowboy roles. I

remember the day he encouraged me to see Seven Men From Now (1956), a Budd Boetticher western that continues to

be one of my favorites.

A lot of western fans will pick John Wayne as their

consummate cowboy actor, but Scott has been a personal favorite of mine for a

long time. He kept his chiseled good looks to the end of his career, not to

mention his lean, six-foot-two bearing, always walking and riding with an easy,

square-shouldered grace. The craggy face as he aged suggested a lifetime spent

in the sun and wind. It was a western face.

I’ll give Wayne his grin and his warmth when the role called

for them, but Scott could also be coolly stern and reserved in a way that could

bring a chill to a scene. The rage behind his steady gaze in Seven Men From

Now gives a depth to his character that you

might only see in Clint Eastwood, for whom it has been a trademark.

Scott didn’t just play himself in his westerns. He was

equally good in different kinds of roles. In Buchanan Rides Alone (1958) he’s the man who gets by with a smile and a

wry comment when he’s outnumbered by a town full of miserable crooks. You

believe him in roles like this that call for his character to stand up for himself,

alone and with no one else to depend on

—

but often with people depending on him, as in another Boetticher film, The Tall T (1957).

In The Man Behind the Gun (1953), he’s a man of more than one identity, pretending to be an

easy-going tenderfoot while he’s really on a mission to stop a vicious plot to arm

secessionists. In Riding Shotgun (1954),

he is a fugitive from a lynch mob, wrongly believed to have held up a stagecoach. And before his

retirement from the screen, he left fans with a memorable performance as an

aging ex-lawman in Sam Peckinpah’s classic Ride the High Country (1962).

So that’s my cowboy western hero for National Day of the

Cowboy. Fortunate for me, he made a whole bunch of westerns, and I look forward

to seeing them all, and then seeing them all again.

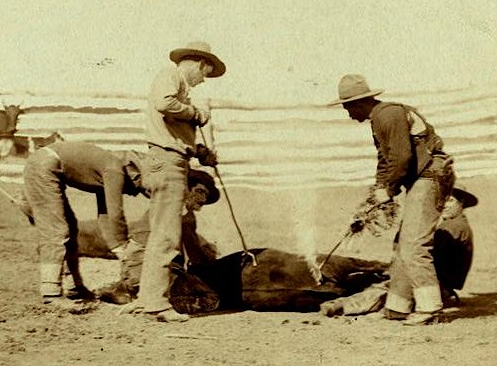

Image credit: Artist, Bill Feuer

Coming up: Tom Lea, The Wonderful Country (1952)