This collection of stories set among ranches and homesteads in Southern California was the early work of an English writer who became a prominent novelist and London

playwright. Born into wealth and privilege, Horace Annesley Vachell (1861-1955)

emigrated to California in 1883, where he operated a cattle ranch with his

father-in-law. These 20 stories, published over a decade after his return in

1900, draw humorously and thoughtfully on that experience.

Character. Of strength of character, the stories

demonstrate a frontier tenacity of spirit. As Vachell notes in his Foreword:

The virtues

that counted in the foothills during the eighties were generosity, courage, and

that amazing power of recuperation which enables a man to begin life again and

again, undaunted by the bludgeonings of misfortune.

The unnamed narrator of the stories and his younger brother, nicknamed Ajax, are rarely touched by genuine adversity. While they discover that

cattle ranching scarcely pays the bills, they have the advantage of owning a

former land grant with grass and water enough in the good years. For the

homesteaders who venture onto the poorer, dryer land, survival is a tenuous

struggle.

|

| William Keith, California Ranch, 1908 |

For their part, the

brothers don’t always exercise good judgment in a story. Ajax sometimes meddles

in the lives of other characters with unexpected results. With no more

knowledge of women than can be gained from a “profound study of high

literature,” he plays matchmaker for a bashful bachelor. Discovering too late

that the bride-to-be expects her groom to take the temperance pledge, Ajax has

to invent a scheme to break the engagement without risking a breach of contract

suit.

One of the best

stories in the collection is surely “One Who Died,” about two English

remittance men. It illustrates how the West absorbed men who came there as

outcasts from homes far away. Gentlemen they may be, but they lack character.

Free to continue living indolently, they are an embarrassment only to

themselves.

Reinventing

themselves at will, the two men in this story fake the death of one of them to

collect funeral expenses from the family back in England. With the money, they

buy a saloon and become prosperous. All goes well until the father of the

“dead” man comes to California to visit his son’s grave. From beginning to end,

the story makes for a memorable moral tale.

|

| William Hahn, Ranch Scene, Monterey, California, 1875 |

Women. In the opening story, “Aletha-Belle,” the young

woman of the title is a book agent, selling a sentimental volume door-to-door

about motherhood, called The Milk of Human Kindness. Given the kind of salesmanship required of

her line of work, she is expected to have “the hide of a rhinoceros, the guile

of a serpent, the obstinacy of a mule, and the persuasive notes of a

nightingale.” But she turns out to be a “thin, slab-chested figure” with

a “prim New England accent,” who looks no more then 18.

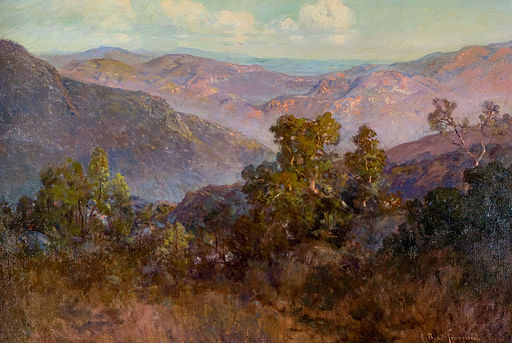

|

| John Bond Francisco, The Foothills of California, c1929 |

Villainy. In general the characters in these stories are

no better or worse than they have to be. The worst of the lot shows up in

“Dennis,” about a hard-luck loser whose sweetheart, Mamie, marries a villainous

lumberman, Tom Barker. The name Dennis, we are told, is synonymous with

underdog, and so is Dennis, who follows Barker and his bride to a lumber camp

in British Columbia.

Taking the

opportunity to torment Dennis further, Barker hires him even though he has no

lumbering skills. He also buys a miserable dog, which he names “Dennis” and

then brutally punishes it, just as he beats his terrified wife. But Mamie won’t

leave her husband, though she hates and fears him. It would mean breaking one

of the Commandments.

Dennis decides he

will have to break one of the other Commandments to free her from her wedding

vows. Dennis the dog, however, saves Dennis the man from having to commit

murder. Taught to fetch, the dog retrieves a lighted stick of dynamite and

drops it at Barker’s feet just as it explodes.

|

| California ranch, C. Hart Merriam, 1903 |

Cowboys. Only two stories feature cowboys, and they are

true to stereotype. Rough and unpolished, they can provide comedy, as in “A

Poisoned Spring,” where three of the brothers’ ranch hands get alarming news

from a visiting professor from the Smithsonian. He informs them they have

consumed fatal amounts of water from a poisoned well on the property. They are

infected with deadly microbes related to the venom of rattlesnakes.

Sent to the

bunkhouse and given whiskey—the commonly administered antidote for

snakebite—they decide to pay a visit to their girlfriends in what may be their

final hours. Still drinking, they enlist the girls’ sympathies and finally pass

out. They wake the next day with hangovers and learn that the quite addled

professor has been taken to the county hospital and put in a strait jacket.

Style. The narrator tells his stories with a wryly-philosophic

tone. Harsh judgments are left unsaid. The natural generosity in his opinion of

others gives meaning to the word “gentility.” His brother Ajax, however, often

speaks what the narrator may be thinking. When someone says of a miserly man,

“I reckon Mr. Spooner must have thought the world of his little one,” Ajax

grumbles that as much could doubtless be said of a vulture. With no

little embarrassment, one story told at the brothers’ expense ends by noting

that there are “two morals: both so obvious that they need not be recorded.”

|

| Horace Annesley Vachell |

Wrapping up. Vachell went on to produce a prodigious number

of novels, plays, story collections, and memoirs. It is said that during his

lifetime he published 100 books. His numerous novels are chiefly set among the

privileged classes of England. He attended Harrow and is best known for his

novel about that esteemed institution, The Hill (1905). Among more than a dozen of his plays,

seven were adapted to film

during 1915-1936.

Bunch Grass is currently available online at google books

and Internet Archive, and also for kindle and the nook. For more of Friday’s

Forgotten Books click on over to Patti Abbott’s blog.

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

Coming up: Glossary of frontier fiction: B

Some beautiful images there. I've always been a fan of landscapes.

ReplyDeleteI gather that the railroads put artists to work portraying the West as a draw to destination sites, especially national parks.

DeleteMany of the westerns (or near westerns) I read have emphasised on the capacity of the West to "absorb" people from far-off places, people who made the Frontier their new homes. I suppose the rural-to-urban shift that we see even today is reminiscent of those times. I liked the description of the young woman in the story "The Milk of Human Kindness" — such fine writing.

ReplyDeletePopulation shifts like that are interesting all right. California, I believe had the most diverse population. I'd guess it continues to have that reputation today.

DeleteThanks for the intro to Mr. Vachell. So many faded names in the history of book writin'...

ReplyDeleteNot just faded. Vachell may be remembered by theatre history folks. I wonder if anyone has revived any of his plays.

DeleteAnother shift of population is going on now with Texas beating out Arizona for in-migration.

ReplyDelete