|

| ebook edition |

The novel teems with

figures from frontier history: Wild Bill Hickok, Sitting Bull, George

Armstrong Custer, Gen. Nelson Miles, and Texas Jack Omohundro. Queen Victoria,

Theodore Roosevelt, and the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia make appearances. We

also get to know the man’s long-suffering wife Louisa and their children, as

well as his several business partners, who both used and abused his trust.

Estleman notes in an

afterword that accuracy in a book about Cody is no easy task. With the help of

Ned Buntline, the press, and Cody’s own fevered imagination, any record of his

life was sure to be highly colored—when not wildly exaggerated. Print the

legend was the general rule.

|

| William "Buffalo Bill" Cody |

Narrative style. Portraying the frontier West as a world that

scorned temperance and moderation, Estleman marshals language to achieve a

similar effect. His sentences are crowded with sharply precise verbs and

adjectives. Words almost tumble over each other.

Big Isaac

Cody, whiskered like a border raider, with the build of a canal-boat puller and

the eyes of a boy on his first visit to a Leavenworth whorehouse, rested a

horned hand on his eight-year-old son’s shoulder and watched Kansas bleed.

That’s the first

sentence of chapter one, and its careening storytelling style, overflowing with

metaphor, sets the tone for the whole novel.

Abrupt

scene-to-scene shifts catapult the reader forward in skips and jumps. Often a

scene is well underway as it begins. We don’t know where we are or what’s going

on until paragraphs later, and then only by paying attention to the dialogue.

And the dialogue

itself is typically facetious and understated. Leading a rescue party to find

lost cavalry troops in the dead of winter, Cody comes upon a starving and

near-frozen Hickok trying to warm his hands at a buffalo chip fire. There

follows this exchange:

“What you

doing, Wild Bill?”

“Well,”

drawled the other, “when they got

hot enough I was fixing to eat my fingers. But yours are fatter.”

In the rough and

tumble narrative flow, extraneous details compete with description of the

central action of a scene—as when a cavalry officer orders his troops to attack

an Indian camp and the bugler “disremembers” how to sound the charge.

Historical

characters make entrances under their birth names, and their identity isn’t

discovered until pages later. A man named Jim turns out to be Hickok, and a

sharpshooter, Mrs. Phoebe Butler, is eventually revealed as Annie Oakley.

Structure. Adding yet another twist to the narrative, Estleman begins the novel at the end of Cody’s life, as he makes a farewell speech to a Wild West show audience. Later, we cut away from his earlier years to a deathbed scene and later still to an account of his burial.

|

| Sitting Bull and Cody, 1885 |

Themes. Estleman maintains a comic tone almost to the

end of the novel. And in the manner of true comedy, he and everyone else in the

story are essentially unchanged from beginning to end. In Cody’s case, the man

is portrayed as an innocent, never outgrowing the boy he was when, hardly

twelve years old, he takes a job with a long-haul freighter to support his

widowed mother and siblings.

But there’s a darker

underside to innocence that Estleman only hints at. As the great man’s fortunes

decline and the men he has known and trusted grow sick and die one by one, a

growing degree of melancholy sets in. The frontier past is not romanticized or

glamorized, but when Cody grows old there’s a sense of something gone forever—a

promise maybe that was never fully realized.

Cody’s years on the

frontier coincide with the subjugation of the Indian tribes. Cody sees that

process as inevitable. We see him as a young Indian fighter, who later manages

to win their grudging respect. Sitting Bull, for one, joins the Wild West show

for a season. And a contingent of Indians goes on the road with Cody, even to

Europe, supplying frontier authenticity as they chase the Deadwood stage and

reenact the Battle of Little Bighorn.

But there’s never

any doubt in Cody’s mind about the dominance of white civilization. Untroubled

by justice or injustice, he accepts that it’s a white man’s world, and if

Indians refuse to negotiate for what’s in their best interest, then tough luck.

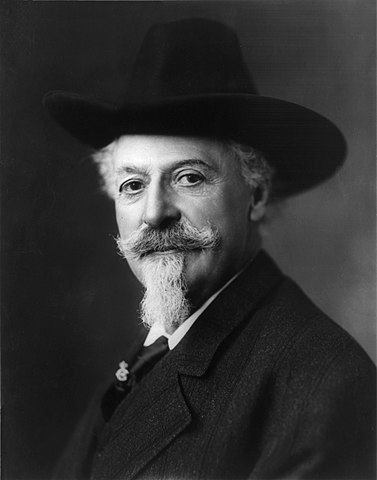

|

| Cody, 1911 |

First it’s the dime

novels and the newspapers, then the theatrical productions and the Wild West

shows, and finally the movies. At some point, early on, his life is no longer

his own. It’s been monetized. Properly managed by others, it makes him a

fortune, but with his spendthrift ways, he winds up in debt. He may die a

prominent figure in the eyes of the world, but that is hardly a crowning

achievement. Lingering at death’s door, he drifts among memories of the past

when he was all himself and nobody else.

Wrapping up. This is a thoroughly entertaining novel, with a

story about a remarkable man who is embedded deeply in the popular history of

the American frontier. The irony is that he did much to invent that history and

his role in it. And Estleman finds just the right way to tell it—like a busy,

colorful theatrical production, the stage crowded with performers, the action

illuminated by fireworks.

This Old Bill is currently available at amazon and AbeBooks and for kindle and the nook. For more of Friday’s Forgotten Books, click on

over to Patti Abbott’s blog.

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

Coming up: The show-not-tell of subtext

I've got this one. Had it a long time but haven't read it. I'll move it up on my list.

ReplyDeleteRon, I am glad you reviewed this book for though I have only read one novel by Estleman I am already a fan of his writing. I would have understood Buffalo Bill Cody's life better had I read "The Life of Buffalo Bill" by William Cody that I have. The back of the book says this is his story in his own words and the first chapter is titled "How I Killed My First Indian" (Real West, August 1990). It left me confused for I didn't think Cody had written anything remotely biographical.

ReplyDelete...assuming, of course, that the book is a reprint.

DeleteCody had ghost writers eager to sell books about him. After a time, if he wrote anything about himself, it was colored by the stories that had been made up about him.

DeleteDaunting to take on a character whose legend is more grand than the real person could ever be. I'd really enjoy reading this one.

ReplyDeleteGreat review, catching the ways Loren plumbed Cody's nature, and also catching Loren's genius with language. This has long been one of my favorites.

ReplyDeleteI admire Estleman's crime novels, so I'll look out for this book. It seems to take a view of Cody very like that of Arthur Kopit's play Indians, filmed by Robert Altman as Buffalo Bill and the Indians- not one of his better films, unfortunately.

ReplyDeleteBuffalo Bill was an interesting fellow. I've just been doing some research on his relationship with Wild Bill Hickok, who could draw in crowds despite being a terrible actor who suffered from stage fright!

ReplyDeleteJohnny Boggs has a novel, EAST OF THE BORDER, about Cody, Hickok, and Texas Jack Omohundro on the stage together.

Delete