|

| Huck and Jim, 1884 |

In Twain’s novel, the slave Jim is actually a full-fledged

character, and Twain ascribes to him dignity as a member of the human race. You

can’t really say that about most of the nonwhite characters in the novels of other

mainstream writers. On the occasions when they appear in popular fiction,

African-Americans, Native Americans, Asians, and Mexicans are typically

peripheral characters portrayed in caricature. They may not even have names.

White supremacy is simply assumed in most novels, and there

are degrees of whiteness. To call a man “white” carried the meaning of

“decent,” “honest,” “generous,” and “honorable.” The word also meant

“respectable” and “civilized.” Obviously, not all white men were. The

connotation survives today in phrases like “that’s white of you.”

Occasionally one finds white supremacy actually voiced as

a doctrine. Jack London’s A Daughter of the Snows (1902) applauds the survival of the fittest and sermonizes about the

superiority of the white race. Rarely are notions of this caliber openly

questioned or challenged by other writers, but the few examples that exist are

worth noting.

|

| Native Americans, 1900 |

The title character, Ramona, is the orphan daughter of a

white father and Indian mother. Falling tragically in love with her is a young

Indian, Alessandro, a gentle soul who has learned to speak Spanish and can also

read and write.

Seeking sympathy and understanding for Indians, Frederic

Remington takes a different tack in John Ermine of the Yellowstone (1902). The hero of this novel is a white man raised

by Indians who attempts to reenter the white world as an Army scout. As he

falls in love with an officer’s daughter, he is caught in a collision of

cultures, and his story ends tragically, as well.

Mary Austin’s Isidro (1905) embeds in her romance of Old California a critique of the mission system’s treatment of Indians. She portrays their conversion to Christianity as no better than enslavement, and she makes no secret of the flogging of Indians for infractions of mission rules. She portrays them as peaceful people wanting no more than to live as they please, where they please. In their wish to be left alone by whites, she says, they were not savages. She points out that they knew nothing of torture, scalping, or massacre.

|

| D. Farnum, Red Wing, The Squaw Man, 1914 |

Ryan’s heroine, Rachel Hardy, is of a different mind and

develops respect and sympathy for both Genesee and the Indian tribe he has

befriended. While she may not quite countenance sexual contact between races,

she learns in the novel that to know all is to forgive all.

“Breeds.” Modern

readers of these novels may be surprised to discover the belief that mixed-race

characters exhibit not the best but the worst traits of both races.

“Half-breeds” are normally cast as villains. Showing them as admirable or

heroic is uncommon. Only a few, like Ridgwell Cullum in The Story of Foss

River Ranch (1903), break with this pattern. His character Jacky is a

“quarter-breed” woman who competently runs a ranch for a white man who has

befriended her. While beautiful and intelligent, she has an independent

temperament that is nevertheless attributed to her mixed ancestry.

|

| Snapping Turtle, "Half-Breed," 1834 |

It was her destiny to be the

daughter of a half-Sioux and a border adventurer, and to feel the counter

influences of the two races make forever of her heart a battleground.

In the closing chapter, she accepts being torn between the

traits she has inherited. Unlike the shallow and frivolous or the domineering

women who populate the pages of this novel, Judith is fated to experience her

life with a fierce emotional intensity.

It was in her inheritance to

know and live for the wild thrill of ecstasy in her pulses, to feel trembling

joy and despair and frantic hope, that exacted its tribute hardly less

poignant; as it was also to feel a shivering sensitiveness in regard to the

loneliness and bitterness of her life, to have the same measureless capacity

for sorrow that she had for loving.

Mexicans. Writing

as a Mexican-American, Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton told of the injustices

experienced by Mexican landowners after California became a state. The Alamar

family at the center of her novel The Squatter and the Don (1885)

experiences the prejudice of white America, which considers them members of a

conquered people.

They are stereotyped as “greasers”: lazy, thriftless,

ignorant, and lacking ambition. Though he has worked in a bank, one of the

family is unable to find suitable employment in San Francisco because of his

ethnicity. He resorts to doing manual labor for two

dollars a day, which eventually breaks his health.

|

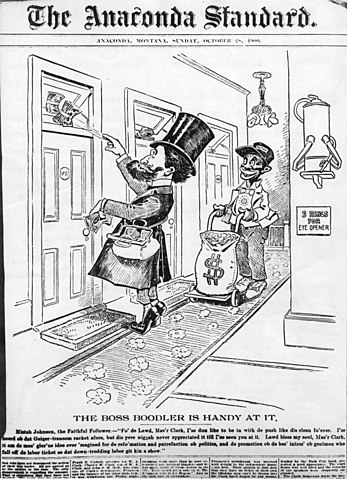

| Black caricature, 1900 |

He surprises the other delegates by being in support of a

Democrat from Georgia. He argues that the Republican Northerner, a shabbily

dressed judge, lacks the kind of polish that would recommend his character. The

candidate from Georgia, by comparison, has the dress and manner of a proper

gentleman, whom the black delegate feels he can trust. His endorsement swings

the convention in favor of the Democrat.

Asians. Chinese

characters appear commonly as cooks or owners of laundries, and the occasional

Japanese work as house servants. They are sometimes named and may have a line

of dialogue, though in barely readable English. Generally Asian characters are

no more than stereotypes.

|

| The Yellow Terror |

Another can be found in Alfred Henry Lewis’ Wolfville (1897). A Chinese man, Lung, who runs the town

laundry is alluded to as a “slothful Mongol,” an “opium slave,” and a “heathen

from the Orient.” When a white woman arrives with plans to open her own

laundry, the residents consider it a disgrace for her to compete for business

with a “Chinaman,” and he is run out of town.

Wrapping up. Meanwhile, mainstream popular novels of the period are full of racial

epithets that make Huckleberry Finn seem tame by comparison. The

dominance of white characters and white points of view in this fiction reminds us that mainstream novels were meant for a white audience. It also

reminds us of how other voices were not heard and other stories went

untold.

All the books mentioned above can be found online at

google books and Internet Archive.

Image credits:

Wikimedia Commons

Painting of Snapping Turtle by George Catlin

Painting of Snapping Turtle by George Catlin

Coming up: Rio Lobo (1970)

Whenever I read these older books I make a point to myself of remembering that they are such a product of their time. Only in that way can I enjoy them despite the often very negative views on minorities.

ReplyDeleteIt's worth noting that the Choctaw "half-breed" Snapping Turtle, better known as Peter Pitchlynn, spent much time lobbying for his people in Congress, and was eventually their Principal Chief. He was only a "half-breed" to the whites. Great piece, thanks for doing it.

ReplyDeleteGood article. I was startled to reread after 40 years Ian Flemings Live and Let Die. The film was not much better.

ReplyDeleteThought-provoking subject -- hard to believe we were so intolerant back in the days! I take it as a challenge to create believable characters of all races.

ReplyDelete