Writing in 1913, H. L. Mencken called Mark Twain (1835–1910) “the true father of our national literature.” In 1934, Ernest

Hemingway ranked the author with Henry James and Stephen Crane and opined, “all

of American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.”

More interesting from the viewpoint of frontier fiction,

F. Scott Fitzgerald ventured in 1935 to call Huckleberry Finn “the first journey back.” He says of Twain, “He was

the first to look back at the republic from the perspective of the west.” And

it’s worth remembering that Twain himself had traveled in the West by the time

he wrote this novel of life on the Mississippi, set during the years of his own

boyhood before the Civil War.

One of many ways to read the novel is to see it as a

prequel to a tide of frontier fiction that followed. Huck’s is the backstory of the typical hero of the cowboy western. Think of how many of them have a central character who started out like him, either an orphan or a runaway, who has come west—"lighting out for the Territory," to use his words for it.

|

| Cover of first edition |

Consider the basic elements of the mythic cowboy: his

preference for drifting and living outdoors, carrying a rifle and shooting game

for food, getting in and out of scrapes while relying on his wits and knowledge

of survival skills. These elements of the myth, along with visits of loneliness

and attachment to a "pardner," are already there in Huck.

Huck’s basic decency is another parallel. Unschooled and

unadulterated by pious religious beliefs, he does the right thing, even when he

suspects that it is wrong. He is haunted with guilt that he has broken the law

by helping the slave Jim run away from his owner, Miss Watson. While reason may not lead

him to question slavery itself, he gradually comes to acknowledge Jim’s worth

as a human being—and as a friend.

Plot. For anyone

who hasn’t read any or all of the novel, you no

doubt know the novel’s basic plot. Huck Finn and Jim take

a ride on a raft down the Mississippi River. Along the way, they have several

adventures (for a full plot synopsis click over to wikipedia).

After separations and reunions, Huck eventually winds up

on a plantation far down river, where Jim has been captured as a runaway slave

and is being held captive. There they are joined by Tom Sawyer, who happens to

be visiting relatives on the very same plantation.

|

Themes. You could

write a book about all that’s going on in this novel, and it would be only a small part of the growing discourse among other readers who have also found much to say about it.

What struck me was how so much of the story is about subterfuge. Huck is forever making up stories about himself, pretending to be someone else to escape

detection. Early on, he fakes his own murder. Soon after, he’s disguising

himself in a girl’s dress.

Then he and Jim are joined by a couple of hucksters who

give themselves phony identities as nobility and run elaborate cons on the

residents of river towns they pass through. Huck gets sucked into these schemes

and ends up telling more lies—once to save three young women from being victims of a

hoax.

The nuttiest turn comes at the end as Tom Sawyer hatches

an elaborate plan to free Jim. His head full of far-fetched adventures found in

storybooks, Tom isn’t satisfied with simply sawing away a chunk of log to let

Jim crawl out of the shed where he’s being held. Days pass as Tom plays out

rescue fantasies, and not only does the eventual escape fail, but Tom gets shot

in the leg.

Hemingway didn’t like this ending and told readers to stop

before wading into the last chapters. Twain scholar Charles Neider makes a

similar argument and cut these chapters by almost two-thirds (over 9,000 words)

for his 1985 edition of the novel. Tom Sawyer may have been Twain’s sentimental

favorite, as Neider assumes, but I’m not so sure. Tom’s love of romantic

adventure is both foolhardy and perilous. It nearly gets him killed.

Hemingway didn’t like this ending and told readers to stop

before wading into the last chapters. Twain scholar Charles Neider makes a

similar argument and cut these chapters by almost two-thirds (over 9,000 words)

for his 1985 edition of the novel. Tom Sawyer may have been Twain’s sentimental

favorite, as Neider assumes, but I’m not so sure. Tom’s love of romantic

adventure is both foolhardy and perilous. It nearly gets him killed.

Though Huck is making up stories and hiding behind false

identities from beginning to end, it’s always to protect himself and Jim. His life is

an adventure. He doesn’t have to manufacture one. Tom is still a boy at the

end, living in a boy’s fantasy world. Self-reliant Huck has grown into

adulthood. His adventures have forced him to confront some of life’s paradoxes and imponderable truths.

As one example, there’s what he learns of fairness,

justice, and morality. Conscience, he discovers, is not a helpful guide. After

he arrives too late to keep his con artist friends from being tarred and

feathered, he thinks:

I warn’t feeling so brash as I was before, but

kind of ornery, and humble, and to blame, somehow—though I hadn’t done nothing. But that’s

always the way; it don’t make no difference whether you do right or wrong, a

person’s conscience ain’t got no sense.

At the end, Huck is still a boy in years, and depending on what

happens to him afterwards, there’s no telling what sort of man he will become. But he’s good-hearted and resourceful, with good instincts, and you can

see versions of him showing up before long in the outpouring of frontier

fiction that came in the decades that followed.

Jim. I suppose you

can’t talk about this novel today without at least mentioning the use of the

n-word. Read other popular fiction from Twain’s time, and you'll find the

casual use of racial epithets to be common. (See my discussion of this topic a while ago.) The difference in Twain is that (a) it’s hard to find

another example like Jim of a fully formed black character in the work of Twain's contemporaries, (b) Twain portrays him with notable dignity for a man

living under conditions of slavery, and (c) Huck’s use of the word “nigger” is

surely an accurate representation of its general use at the time.

Yes, Jim is still a stereotype. But malice seems not to

have been intended, and most of the other characters seem no less stereotyped.

After all, the book is a comedy and not a melodrama or a tragedy. As for use of “nigger,” Twain could not have known the word would evolve almost

exclusively into a racial slur a century later.

I’d also argue that you can’t immerse yourself in history

without acknowledging the racial attitudes of the time. Selectively euphemizing

or expurgating the past is both whitewash and denial. I’m OK with the novel as

Twain wrote it, and I’d encourage readers to swallow any objections and read it

for the humanist view on race that he advocates.

Wrapping up. Reading

Huckleberry Finn, I have discovered that I’d probably never

read the entire novel before from beginning to end. I knew Hal Holbrook’s

one-man show, buying an LP recording while in Hannibal, Missouri, in 1960.

Later, I got to see him do the show live at the Clemens Center in Elmira, New

York. Besides that, I must have read only excerpts. The full novel is a

wonderful, casual, almost lazy read and a forerunner of American picaresque

novels and road movies.

Though episodic, there is the connecting thread of the

journey down river and the growing suspense as Jim risks capture as a runaway

slave. The tenderness that develops between Huck and Jim is also a surprise.

You find yourself recalling Leslie Fiedler’s 1948 essay on male bonding in

American fiction, “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck, Honey.”

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is currently available online at google books and in

text, audio, and video formats at Internet Archive. It can also be found at

amazon, Barnes&Noble, Powell’s Books, and AbeBooks. For more of Friday’s

Forgotten Books, click on over to Patti Abbot’s blog.

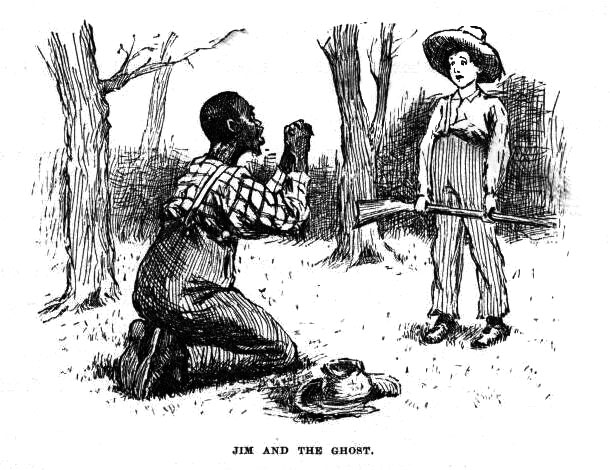

Image credits:

Wikimedia Commons

Illustrator, Edward Winsor Kemble (1861-1933)

Coming up: Glossary of frontier fiction

I was fairly young when I read it. I'd already started enjoying SF and fantasy so in one way it was fairly tame to me. But the characters grew on you. I remember it fondly now.

ReplyDeleteWhat you have written is really first rate, Ron, as is the book you so eloquently summarize.

ReplyDeleteRon, thank you for a wonderful review of a timeless classic. I read Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer in my teens with an open mind as one is wont to do at that age. It'd be interesting to revisit the books now and see how I feel about them. A couple of years ago, I re-read "Robinson Crusoe" and enjoyed it immensely. I don't recall any race issues concerning Man Friday. Daniel Defoe advocates a similar "humanist view" although the rescued native is employed by Crusoe as his servant. The bond between them is not unlike the one between Huck Finn and Jim.

ReplyDeleteWherever there's an assumption about racial superiority or inferiority I think it's safe to say you've got some form of racism. There may be no malice intended, but that doesn't erase it.

DeleteRon, I couldn't agree with you more. I could overlook the obvious superiority of Crusoe as there was no serious racial prejudice of any kind. It was a nice story and I read it thus.

DeletePrashant, there are certainly people of late who are uncomfortable with Man Friday, as well (and the once-common phrase in the States, at least, "Girl Friday" because to say Woman Friday would be Weird Or Something).

ReplyDeleteI think Twain knew what he was about in not flinching from the use of the word, and other words, too...if there is a more damning treatment of the insanity of chattel slavery, including Stowe's, I'm not sure I'm aware of it (at least until Octavia Butler's KINDRED). Huck's certainty that he's going to Hell for helping Jim, and deciding that he just doesn't care, is a ferocious critique of the notion of racial inequality...and anyone who can't see that, I think, has some difficulties with reading comprehension that a simple chat won't clear up.

And, of course, FINN was followed by two more Sawyer/Finn/Jim stories, at least I think Jim was in the fourth, the amiable TOM SAWYER ABROAD, and the deadly dull, even given its brevity (a novelet at best, while ABROAD is a novella), TOM SAWYER, DETECTIVE. Perhaps DETECTIVE also didn't appeal to me due to its similar tone of weariness to the last chapters of FINN. Charles Neider, btw, rather than Seider.

Thanks for the correction, Todd.

DeleteYou're quite welcome...just for swank, as I recall Jim is the narrator of ABROAD. Think DETECTIVE might be, but probably isn't, third-person omniscient. They're both almost certainly online for the checking...interesting choice for the Abbott FFBstakes (I've just been made aware of the porny potential meaning of FFB by looking at the links that brought people to my blog.)

DeleteTodd, thanks for the additional insight into Twain and the mention of his other books. I haven't read "Tom Sawyer, Detective" which I have in an ebook. His name crops up almost every time there is a debate on sleuths in early crime fiction. It'd be nice to see more reviews of classics like "Huckleberry Finn" for Patti's FFB.

DeleteThanks for the review of a favorite book--I read Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn in school, but have read Huck Finn two more times as an adult. The river and the friendship and the lure of the west--I supposed they all play into my psyche.

ReplyDeleteThis is a great post, Ron. Has me digging for my copy right now. . . .

ReplyDeleteI've read THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN at least six times over the past five decades ... Now you've got me thinking it's about time to crack open that classic again, Ron.

ReplyDeleteEach time I read it, I find something new to savor, some new layer to its many depths. It is *the* great American novel and certainly among the most significant of all time.

Thanks for bringing it to mind again.