Review and interview

Review and interviewThis is a heckuva western novel that more than lives up to its unusual title. Mitten knows the conventions of the genre and then turns them inside out to create a sprawling narrative that ranges all over the state of Colorado. The cast of characters includes working cowboys, the worthy citizens of several Rocky Mountain settlements, and the members of an outlaw gang.

Their lives converge on a fatal day in 1887 when a stage

hold up is interrupted by a cattle drive. A traditional western might start

with an incident like this, but Mitten puts it squarely in the middle of his

story. The first half of the novel is prologue to it, as we meet his characters

and get into the rhythm of their lives, both for good and ill.

The second half portrays the aftermath as it follows a

dozen or more characters as they disperse in all directions. Their lives

intersect with those of multiple other characters, and for a while Mitten is

tracing their adventures along eight different storylines. The cast of

characters eventually numbers 75 or more men, women, and children. That

includes cameos by the likes of Doc Holliday and Soapy Smith.

|

| Leadville, Colorado, c1880 |

The title of the novel refers to a scene in which cause,

effect, chance, and coincidence meet again as they have before in the novel.

One of the outlaws escapes being shot for a horse thief by hiding in a grave he

is digging for another man. He happens to have a bottle of whiskey with him.

In the end, the incident that begins it all—the shooting

of a sheriff—is finally resolved and justice is served. And not without some

ironies. Meanwhile, life goes on for the other characters (at least those who

survive), as the events and incidents of the novel take them onward, leaving

the past behind. Mitten seems to be saying, nothing ever really ends, and a

reader may sense the possibility of future sequels.

Style. Mitten

shows a gift for dialogue and the vernacular. When a cowboy sees a man in a

slicker (something new in 1887), he admires it and says, “Need me one of

these.” That’s the kind of line you can hear being said.

The narrative also shows an unusual appreciation for the

impact of death. Characters experience shock and grief when someone is killed,

and the feelings do not soon wear off. Mitten notes how death hits hard those

least accustomed to it. A bunch of young cowboys are shaken as the posse they

are riding with comes upon the bodies of two men shot dead.

|

| Colorado mountains, Albert Bierstadt |

One of those acts of transgression is the stealing of an

heirloom pocket watch inscribed with a loving message from a man’s wife. The

tenderness and civility of that sentiment feels violated as the watch passes

into the hands of a lawless man. Ironically, as cause, effect, chance, and

coincidence play out in the novel, the theft leads to the undoing of the thief.

The outlaw Bill Ewing comes closest to being the center

thread in the novel. Yet Mitten breaks with convention by making him neither a

truly bad man nor a good-bad man. Other men in the novel are more vicious,

cold-blooded, or mean, but Bill has no particular saving grace either. In the

end, he gets what he deserves.

Sipping Whiskey in a Shallow Grave is Mark Mitten’s first novel. It is currently

available in paper and ebook formats at amazon and Barnes&Noble.

Mark is also a musician and has worked professionally with

horses. Until recently a resident of Colorado, he now lives in Minnesota. Mark

is a member of Western Writers of America and Western Fictioneers. His novel Sipping

Whiskey in a Shallow Grave was nominated

for a Peacemaker Award. Mark has agreed to spend some time at BITS today to

talk about writing and the writing of Sipping Whiskey. It’s a pleasure to have him here.

Mark, talk about how the idea

for this novel suggested itself to you.

I’ve spent most of my life in

Colorado, and a lot of time in the mountain towns. Much of the history of the

state is grounded in the same time period as the novel, the mid to late 1800s,

and there is still an Old West vibe in many of those towns. I love the

Victorian architecture, which is often maintained.

A few years ago, when I first

started writing Sipping Whiskey in a Shallow Grave, I was spending some time up in Leadville (a town that

sits at 10,000 feet in elevation). Leadville used to rival Denver in size,

during the silver boom. There are still a lot of old mines up there, and

evidence of that boom is everywhere you look. The history is very present and

it was very inspiring to me as a writer.

I also enjoy reading historical

books about that time period. Several books really fueled the cause:

Bob

Fudge: Texas Trail Driver

6000 Mile

of Fence: Life on the XIT Ranch of Texas

The Negro

Cowboys

One more thing. I have worked in

the horse industry off and on over the years. Of course, there are two main

branches of horsemanship: Western and English. The Western style is

inextricably linked to the American West, and I’ve always been impressed by the

working cowboy. There is a something about the ethos, identity, and connection

to the outdoors that defines the working cowboy—and it really appeals to me.

So, as a creative person, it is no surprise that my imagination took me in the

direction of a western novel set in Colorado.

Did the story come to you all

at once or was that a more complex part of the process?

It was certainly a process. From

concept to manuscript completion, it took me three years. In the early stages,

it actually began as a screenplay. One of my creative outlets is acting (in

independent films, by Colorado filmmakers). I had played roles in several

westerns, and the experience made me want to write my own film.

That’s where it began—but once I

tried shopping it around, I realized that indie filmmakers usually stick with

their own original storylines. So I realized the best way to get the story out

was to turn it into a novel. And once I shifted the story into a novel format,

it opened up the doors creatively to take the characters in directions you

simply cannot go on film. A novel allows for character development in deeper ways

that a visual medium is not suited for.

Talk a bit about editing and

revising. After completing a first draft, did it go through any key changes?

By the time I completed the final

chapter, I realized that my writing style had matured since I first began. One

key change, was that I scrapped the first few chapters and literally re-wrote

them. I wanted continuity in tone and quality. I also went on through each

chapter and revised, revised, revised. Especially after having gotten to the

end, I felt I was in a position to go back through and re-write anything that I

felt was inferior.

A critical step for me was having

a friend proof-read the manuscript. At this point, after pouring over each

chapter, sentence by sentence, I felt I had done all I could with it. Having a

fresh set of eyes work it over helped weed out further grammatical errors that

I had missed. Once I found a publisher, there were hardly any editorial

notations. I credit that to my proof-reader (thanks, Mark Spellman!)

Did anything about the story or

characters surprise you as you were writing?

The book is divided into three

parts (and a short epilogue). The first part was partly mapped out, having been

based loosely on the screenplay. But once I got into part 2, I was into new

territory. I still had several unresolved character arcs and I knew where they

were going. But I felt a renewed sense of creativity as I moved into the

unknown.

In many cases, I had no plan going

in. No story threads mapped out on a dry erase board. I mainly relied on

intuition and research to carry on. In some cases (like the XIT Ranch

storyline), the story was heavily based on actual historical events and people.

It was a matter of fleshing out the scenarios. Other storylines, like Casey and

LG, and Bill Ewing, were far more intuitive. It was also fun weaving in some

historical figures into the mix, giving them personality and storyline impact.

It was continually rewarding to draw from history to lend authenticity to the

narrative and dialogue.

The cowboy Casey and the outlaw

Bill are both strongly drawn characters. Talk a bit about where they came from.

If a reader is looking for a

distinct protagonist and a distinct antagonist, you’ll realize that with such

an ensemble of characters it’s hard to identify any easy picks. But Casey and

Bill are top contenders. Casey is clearly a good man, wrestling with a broken

spirit. His life becomes about picking up the pieces and carrying on. He

wrestles with guilt, confusion and abandonment. Bill is ostensibly the bad guy.

But as we get to know him, it gets harder and harder to despise him. We come to

understand that everyone has a story—even the worst people we meet.

Sipping Whiskey is a character-driven story. It is my hope that the reader

will close the book feeling a rich sense of closure and satisfaction. After

immersing yourself in the lives of all these people, you feel their angst,

share in their sense of consummation, and walk away feeling that, whether good

or bad, “this too shall pass.” And ultimately, it is goodness that is the most

worthwhile pursuit in a world of social injustice and unfairness.

In Sipping Whiskey, there are people who have experienced being wronged, and

do not realize that some form of justice has indeed been pronounced (somewhere,

somehow). But they carry on. Some

forgive, some don’t. Some fall prey to bitterness, others move on in goodness.

There are also people who do the wronging. Some have a scalded conscience and

don’t give a second thought, while others struggle with shades of regret and

conviction.

Casey and Bill’s storylines do

stand out, and convey this sense of life’s circumvections. Especially in a

story with a good number of characters weaving in and out amongst each other,

these are two strong threads.

How much consideration did you give

to recreating the vernacular of the day?

Quite a lot! I deliberately sought

out nonfiction firsthand accounts from that time period to make it as authentic

as possible. I wanted it to seem like you are listening in on actual

conversations, steeped in their original historical context—which means that a

phrase or term is sometimes unfamiliar to the 21st century reader,

and it might go unexplained. And that’s okay.

I’ve noticed that some westerns,

both book and film, can fall into the trap of western-lingo caricature: “Draw, pardner!” Sometimes, though an

author may be well-meaning, the western genre can lend itself to a rhythm of

language that seems more like parody than period dialogue. I wanted from the outset

to consciously avoid any paint-by-numbers dialogue.

If the novel were made into a

movie, whom would you like to see in the cast?

Tricky question.

Not too long ago, I read an

article about the hypothetical casting of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. Like anyone who has read the novel, there is a great

sense of mystery in who these characters are. Names even seem to be avoided for

key characters, like the kid and the judge. The article threw out some names:

Liam Neeson? As the judge? You gotta be kiddin’ me. It was somehow deflating to

even consider popular actors (regardless of how good they are) to portray these

timeless characters that my imagination had already assigned a somewhat

anonymous vibe to. What about casting it with “unknown” actors, so the film has

a clean slate and the audience has no preconceptions?

Not to say that there aren’t some

amazing western films, because there certainly are—it’s just that it’s hard to

go from a book you’ve read to seeing a film version.

So what to do with Sipping

Whiskey? Of course my gut reaction is to

think that, if Hollywood were to come calling, a big part of me would be

excited and honored. And yet another part of me would be worried about the end

product. When I think about western books being turned into film, few seem to

hold up in my opinion.

Perhaps one must consciously

compartmentalize the book from the film as completely separate entities, and

refrain from comparisons, in order to keep oneself from a sense of proprietary

indignation. And really, art should not be proprietary…once it’s out there and

subject to each audience’s interpretation and reaction. Even the artist (in

this case, author) might find it wiser to disassociate ownership once it is

catapulted beyond reach. Let it become what it becomes, and weigh it on its own

terms.

At this point, after considering

these angles, I think the characters in Sipping Whiskey should stay in the realm of the reader’s imagination. I

had no actors in mind when I created them, and perhaps it should remain that

way—for now.

Is your style of storytelling

influenced in any way by movie westerns?

No. I have seen many western

films, and recognize a variety of storytelling approaches. But when I wrote the

novel, I didn’t have any movie styles in mind. Probably the reason for this is

that my novel (while containing its share of action) is heavily interested in

character development. I believe the narrative shines brightest when it

explores the minds and motives, the dialogue and interaction, of the characters

on a human level. Many western films are the opposite: action driven. Gunfights

and hangin’s.

When I first began, it all started

with a date. I chose a year (1887), and then began diving into research. What

was the historical context? What was happening that year? What happened the

year before? And I asked, who were the prominent figures of the day? Which led

me to Doc Holliday and Soapy Smith. As well as several others, who are lesser

known, but history buffs will enjoy encountering these characters, as well.

(Horace and Baby Doe Tabor; Big Ed Burns; Charley Crouse; most of the XIT crew;

even Kare Kremmling and the Kinsey brothers of Kinsey City.)

There are frequent shifts of

point of view in the novel. Talk a bit about your decision to do that.

Great question, and good eye for

catching on. I did incorporate shifting POV as a deliberate tactic. One main

goal in writing this novel was to create a character-driven story. I wanted to

embrace the freedom of crossing into character minds. Characters' perspectives

can be diverse, just like the people around us.

Somewhere along the line,

single-POV became a red flag in some circles. I'd call the single-POV literary

rule a tenet of conventional wisdom, and in my experience it’s usually other

writers who cry foul—and not non-writing readers. And I do understand the

rationale…if the narrative is hindered by shifting POV, I would agree. But I do

believe shifting POV is not automatically a bad thing. It should depend on its

use and effect on the story, and not simply on its employment. If I’m honest, I am not a big fan of

conventional wisdom—I think it can limit creativity! As an artist, I believe in

coloring outside the lines.

How did you go about deciding

on the novel’s title?

Originally, the working title was

simply The B-Cross. As the story grew

in the telling, I knew that title was going to be inadequate. Once I got to the

point in the storyline where Bill was digging a grave, I knew I had it. But I

saved the exact phrasing for the end of the story, and wove it into the

narrative in a very rewarding moment. I hope, when the reader gets to that

point, it will bring a smile and a nod of appreciation.

What were the creative

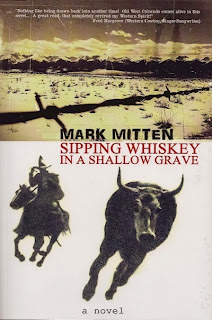

decisions that went into the novel’s cover?

Before I found a publisher, I

first tried self-publishing via Amazon’s Kindle. The cover art was my own

creation.

I took a drive in the mountains

one day, heading to Westcliffe—a beautiful town with the Sangre de Cristo

mountains rising above the valley. It was winter, and I literally parked on the

side of the road, crossed over to a barbed wire fence, and took the shot. Then

I touched it up with a photo editing program to age the picture and alter the

color.

I also decided to create several

pencil drawings for the book. The drawing on the cover is based on an old photo

of a cowboy roping a cow. (In addition to this, I drew an old western saddle

and a bronc rider—which are also included in the book.) The cover was designed

to convey the book’s main subject: Colorado cowboys. I also included a quote on

the front from a present-day cowboy singer who lives in Colorado (Fred

Hargrove), who had written a recommendation for the novel. Fred’s quote lends

it some “street cred” that western readers will appreciate, plus a sense of

professionalism.

When I found a publisher (Sunbury

Press), I simply asked if I could retain my original cover art…and they agreed.

Most of the books that Sunbury publishes have cover art which they make

themselves. And in fact, they chose the image for the rear cover (which is a

black & white depiction of cowboys playing cards.) Turned out perfect.

What have been the most

interesting reactions of readers to the novel?

The only critical thing I’ve

really heard, is that there are a lot of characters. This is true, and I hope it

doesn’t intimidate readers. I would simply say that Sipping Whiskey in a

Shallow Grave is not a “quick” read with

one good guy and one bad guy…like Louis L’Amour or Robert Parker. Instead, go

in thinking of it like some of these TV shows or movies you’ve seen, with an

ensemble cast. You get to know them as you go along, and as they relate to each

other. And the story is more meaningful as a result, with more depth.

What are you reading now?

I just finished Shot All to

Hell: Jesse James, the Northfield Raid,

and the Wild West's Greatest Escape, by

Mark Lee Gardner. The author lives in Cascade, Colorado (a town I know well).

Plus, the book is about the James-Younger gang robbing a Minnesota bank. This

really appealed to me, since I recently moved from Colorado to Minnesota. I’m

also halfway through Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing.

What can your readers expect

from you next?

A sequel is in the works right

now. It is set in the year 1893, about six years after Sipping Whiskey. I’ve

done the research, and I’m about a dozen chapters in.

For readers who like your work,

which other writers would you recommend to them?

For westerns, I would point them

to Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove

series, of course. And one of my favorite authors is Per Petterson—a Norwegian

writer. He has five novels out which have been translated, and they are all

very good. His books are set in various periods in Norwegian history, and his

writing style is very “interior.” Start with Out Stealing Horses…which is not a western at all, but it is an excellent

book.

Anything we didn’t cover you’d

like to comment on?

Promoting Sipping Whiskey is a grassroots effort. My goal is to reach out to the

western and horse community. So getting this opportunity on “Buddies in the

Saddle” is an honor, and a big help.

I wanted to thank you, Ron, for

your time and thoughtful book review. It’s clear to me that you read the novel

closely, got to know the characters well, and really engaged with the story.

That means a lot to me right there. And of course, I appreciate the positive

book review a great deal. The whole point of writing a novel is to connect with

readers. And I am hoping your own blog readers might pick up a copy after

reading about it. By the way, for anyone living in Colorado, Sipping Whiskey

in a Shallow Grave is available at almost

every library in the state. Thanks again, Ron! For supporting the western

community, and western authors.

Thanks, Mark. Every success.

Image credits:

Author’s photo, goodreads.com

Wikimedia Commons

Coming up: James Stewart, The Far Country (1954)

Excellent, thoughtful review that does justice to the novel. Great interview, too. I'm looking forward to the sequel.

ReplyDeleteDefinitely sounds like an unusual story pattern, and I love that title. Great interview. I've not read Mitten so I'll have to give it a look see.

ReplyDeleteGreat interview of a fine author and review of an obviously fine novel. This gives me hope.

ReplyDeleteI love the title. This looks great,Ron and nice interview.

ReplyDeleteRon, thanks for an excellent review of "Sipping Whiskey in a Shallow Grave" by Mark Mitten and the interview with the author. I also liked the unusual title and cover art. The question and answer on shifting point of view was interesting.

ReplyDeleteOne of my all time favorite titles.

ReplyDelete