Review and interview

Review and interview

Some make a killing

while some just get killed in this western mystery set in Leadville, Colorado,

during the silver rush of 1879-1880. And the mysteries multiply after the

novel’s central character, a saloon owner, finds there’s a body in the frozen

mud outside her alley door.

In the pages of this

novel, author Ann Parker has persuasively created a whole social world sprung

into being by the discovery of silver in the Rocky Mountains. Inez Stannert and

her partner, Abe Jackson, keep the beer and whiskey flowing at the Silver Queen

for everyone from the silver barons to the Cornish miners who labor

underground.

At the novel’s

start, Bridgette O’Malley is the cook in the kitchen supplying bread and stew. And

on Saturday nights, the town’s leading citizens gather for a game of

high-stakes poker, with Inez dealing the cards. However, a third partner in the

business, Inez’ husband, has gone missing for most of a year.

|

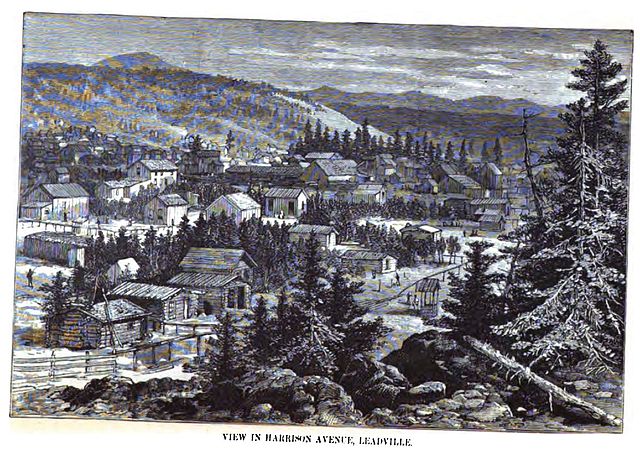

| Leadville, Colorado, c1880 |

Plot. The death of an apparently decent and trustworthy

assayer is passed off as an accident by the town’s truculent marshal. But it

leaves Inez more than a little curious, especially when the man’s office has

been broken into and ransacked. Something suspicious is going on in town, and

she is determined to find out how it came to have fatal consequences for the

assayer.

The mystery deepens

as we meet more characters. A newcomer to town, the Reverend J. B. Sands,

raises a number of questions as he seems unusually worldly for a man of the

cloth. Thoroughly handsome, he is also something of a lady-killer, and Inez

finds herself being romanced by the man.

Romance. Male readers unused to romance fiction will

find the story shifting into quite another key as Rev. Sands and Inez flirt

with intimacy and then yield to it. Love scenes are way different when told

from a woman’s point of view. There’s maybe nothing in fiction more revealing

of the gender gap.

For one thing,

romance emerges from a field of sexual politics in which men are used to

dominating and—especially in the frontier West—outnumbering women. Hollis, the

town marshal, is an extreme example, openly hostile to women. Sands, by

contrast, is a smooth operator, and there’s some question whether his real

motives might be sharply at variance with his polished manner.

Intimacy requires

both trust and surrender. When it leads to unmet expectations and fear of

betrayal, there is a heavy debt of injured pride. That leads to stormy scenes

between mismatched lovers, and this novel has its share of them.

|

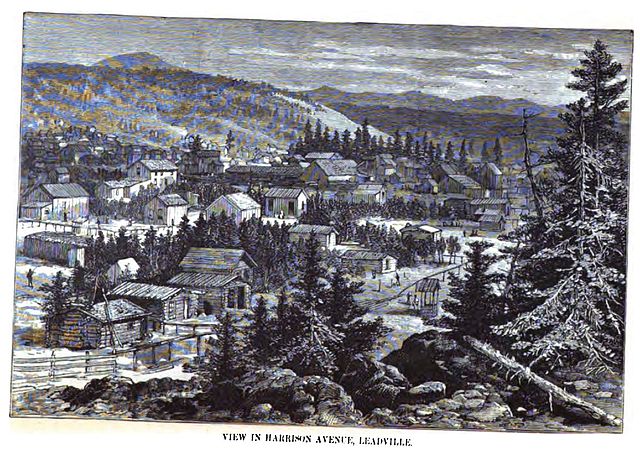

| Street scene, Leadville |

Themes. Injured pride may well have been the title of

the novel, as it runs as a theme from beginning to end. Discussing Milton’s Paradise

Lost, one character describes

the fallen angel, Lucifer, as the victim of it. And injured pride is a

condition that sooner or later gets most of the novel’s characters into

difficulty, including Inez.

The wintry weather

is another constant theme in the novel, as characters trudge through the town’s

frozen streets. Snow is forever falling, and we are often reminded of the cost

to the hems of full-length skirts as women navigate the sludge and mud-caked

walks.

An after-Christmas

soiree at one of the town’s hotels offers a welcome reprieve from the weather.

The chapters describing this elegant event are a genuine pleasure, from the

Eden-like greenery and the invited guests in evening dress to the string

quartet enthusiastically mangling Vivaldi and Mozart. For contrast, there’s the

overheated and dimly lit interior of the town’s high-class whorehouse.

|

| Snow, Leadville, August 1882 |

Women. Parker picks as a point of view character a

woman who would have the freedom and independence of few other women on the

frontier. As a saloon owner, she is freer to mingle with the rougher elements

of town and much less constrained by the requirements of respectability.

Still, as a woman,

she deals with being openly stared at by ill-mannered men, and she is also

vulnerable on the worst streets of town. Thus, she carries firearms, sometimes

concealed, sometimes not. For anonymity, she sometimes dresses as a man. This

gets her access at night to a whorehouse, where she is in search of information

from one of the prostitutes.

She is also not

answerable to the most exacting dictates of Victorian morality. Having Abe

Jackson, a black man, as a business partner would have raised eyebrows among

readers of frontier fiction 100 years ago. Her affair with Rev. Sands would

have absolutely shocked them. A married woman tempted to extramarital sex—and

with a man of God—would have branded her as a “fallen woman.” The thrills she

feels when being touched by him and her awareness of his body in and out of his

clothes would have branded her as wanton.

On a scale of

relative iniquity, however, Parker places her heroine well above the brazen

madam of the town’s classiest “parlor house.” She also ranks above the coolly

arch proprietor of yet another whorehouse, in Denver, who smokes cigarettes as

she discusses the finer points of her trade and her customers.

|

| Prospectors crossing a stream |

Style. The tone is straightforward throughout, with

an undercurrent of suspense, as the stakes rise and the threat of malice

escalates. Now and again there comes an outburst of graphic violence. In the

end, as an element of psychopathology is unmasked and takes over, the violence

gets pretty nasty.

The novel has a

Dickensian cast of characters, including the surprising appearance of none

other than Bat Masterson. There are a couple moments of humor, as when the Rev.

Sands enters the saloon and Inez hears the newly hired piano player segue into

“What a Friend We Have in Jesus.” And one of her employees, a back-bar flunky

named Ulysses, is called “Useless” by everyone.

The mystery itself

is densely plotted, and so many unanswered questions and speculations crop up

that even a seasoned mystery reader may well feel bewildered. At the end, a life-threatening

crisis takes the focus, leaving several details unexplained. Finally, there’s

been so much going on that it takes a couple of chapters of denouement to sum

it all up, including the romantic subplot.

Wrapping up. Overall, Silver Lies is enjoyable on many levels, particularly for

its portrayal of a booming frontier mining town, crawling with life 24 hours of

the day. It was first published in 2003 by Poisoned Pen Press and has recently

been released as an ebook. It is currently available at amazon and

Barnes&Noble for kindle and the nook, also at Powell's Books and Abebooks. You can visit Ann Parker’s website here.

Interview

|

| Ann Parker, Photo by Charles Lucke |

Ann Parker has generously agreed to spend some time at BITS today answering questions about the writing of Silver Lies. I'm happy to turn the rest of this post over to her.

Talk about how the idea for this novel suggested itself

to you.

Silver Lies, and

indeed all the novels that follow, evolved out of a desire to explore this

particular area of Colorado—Leadville in particular—during a specific time—the

boom years of the Colorado Silver Rush. When I first became interested in this

timeframe of Colorado history, we were deep into the dot-com boom here in

California, and I was intrigued by the psychological and economic parallels

between these particular “get-rich-quick” times of vast enthusiasms and

optimism that, to some extent, flies in the face of reality.

Only a few ever rise from rags to riches in any given

boom… but many who fall under the spell of overnight success get swept up in

the hope that, despite the numbers to the contrary, THEY will be one of the

lucky ones. Then, there are the pragmatic types who see the golden opportunity

in feeding the dreams… The folks in Leadville, for example, who “mined the

miners.”

Did the story come to you all at once or was that a more

complex part of the process?

The story evolved as I wrote the first draft. When I

pondered the possibility of writing a book, the opening scene came to me in a

flash and with a feel in my gut: Here is the beginning. I had no idea why

assayer Joe Rose was in such a fix or what he was doing in one of the nastiest

back street alleys in Leadville’s red-light district in the darkest hour of a

cold winter night, nor who was out to get him.

My writing process… particularly for this first book… was

akin to driving in the night with the headlights on. Every chapter I wrote

illuminated the next. It wasn’t until the final third of the book that I could

see to “the end.” At that point, I grabbed a little yellow sticky note—about

two inches square—and scribbled down a handful of key scenes I needed to finish

the story. That was as close to an outline as I got for Silver Lies.

Talk a bit about editing and revising. After completing

a first draft, did it go through any key changes?

Oh my yes. Since my initial writing process was one of

discovery and I wasn’t following a pre-set outline or story arc, my first draft

was massive: about 160,000 words (600+ pages). I was told that, for it to be

marketable, I had to shrink it down. A lot.

I threw out subplots, stripped out characters that didn’t

forward the story, and added another suspect or two (because, despite its

length, I really didn’t have enough suspects). I also worked on paring down the

language. I tend to be very wordy in my first drafts—channeling the 19th

century, perhaps. Even after all this, the end result is still pretty long as

far as first novels go: over 110,000 words.