Review and interview

Having grown up in Nebraska, I’m struck by two things whenever I return. It used to take years for whatever was new on either Coast to make its way there to the middle of the country. Now—whether smart phones or crystal meth—it makes the trip in a week or less. The other thing is that, despite all this constant change, the people who live there remain pretty much the same.

Richard Prosch captures this nicely in these stories set in 21st century Meadows Ford, his fictional small town on the lower Niobrara River. People gamely carry on, long used to playing catch-up with the rest of this crazy country. What they know is that out here the ripple effects from the Northeast Corridor in the East and Hollywood in the West more or less cancel each other out anyway.

My favorite stories in the collection focus on the MFPD, whose line of duty puts them where past and present have their way of colliding. A police chief’s old girlfriend shows up in town decades later driving a car he’d long thought had been junked. His memories of an accident while driving that car intermingle with the daily routine of protecting and serving. Meanwhile, a wind farm worker is found murdered and duct-taped to a tree.

Surely the strongest character in the stories is redheaded deputy Jennifer Rand, a decorated veteran from Afghanistan. Quick thinking, tough, serious, she gets the job done. More than a match for killers who get their loony ideas from bad TV, she’s not above dropping an armed assailant in a church basement.

|

| Bridge, built 1915; county road 552, Pearce County, Nebraska |

Actually, the past is often rearing its hoary head to disrupt the present. When a man finds an old high school keepsake near the scene of an unfortunate farm accident, he tries to find the owner and unravel a mystery. He learns too late that it would have been far better to forget the whole thing.

A man in a car follows a woman who once dumped him. That little display of male ego doesn’t end well either. In another story, there’s a big surprise in store when a contract killer comes back to town to do away with a man who’d once been a boyhood buddy.

A couple stories actually drift out of the distant past like ghostly memories of forgotten times. Anti-German sentiment during the Great War leads to the death of a young woman in a barn fire. The drunken owner of a threshing machine reaches the limits of his neighbors’ patience. In another favorite story, an alcoholic in a rusty pickup befriends and entertains a young girl with an oral history of violent deaths he’s witnessed.

Richard Prosch has a way of telling a story that’s all his own. Out here in his Nebraska, the snow flies and the big sky comes down like a cast-iron lid on the flat horizon. Meanwhile, his rural people live small-town lives where ironies and surprises wait sometimes decades to overtake them.

Meadows Ford Blues is currently available as an ebook at amazon.

|

| Richard Prosch |

Interview

Richard has agreed to be here at BITS today to offer his thoughts on several topics, and we happily turn the rest of this page over to him.

Richard, another Midwestern writer, Nelson Algren, said that ruthlessness and a sense of alienation from society are as essential to creative thinking as they are to armed robbery. Has that been your experience?

Oh, yeah, absolutely. Growing up on the prairie, a thousand miles from all the places we heard about or read about in the media certainly alienated us from the larger culture.

But the paradox is that my personal response to that alienation, my attempts to reach farther, seek harder, find better answers, also then alienated me from the already alienated locals. Tom Brokaw, who grew up in South Dakota said of the Midwest, “there is so little around you intellectually that you reach out for broader source material.” That’s definitely my experience.

As for being ruthless, well, you can’t get too comfortable in your social circle, can you? I think Algren also said something about being a good bell-hop: that’s not the writer who will be remembered. I’m skeptical of writers who too much love the crowd.

What would be lost in these stories if they were set in some other place?

A few of them could be set in any small town in rural America. I’ve lived in the South Carolina sticks and “Just Pretending” or “Fool Me Twice” could work there just as well as Nebraska.

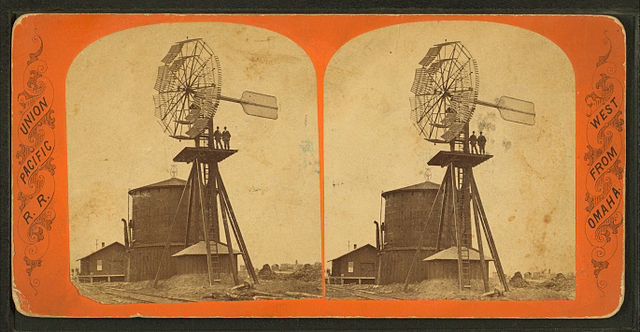

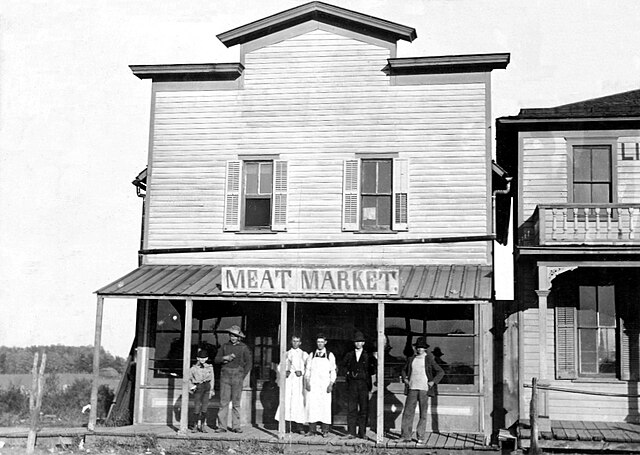

When I was a kid, and certainly when my parents were kids, each of the small towns I knew had its own identity. They were hubs of commerce, sometimes with a railroad station or the perfect stop over on the Meridian and Lincoln highways. And each possessed an ethnicity that revealed its origins.

Once the routes changed and the farms consolidated, those towns had no real reason to exist. What purpose do they serve now beyond housing the old folks that once worked there? So I think there’s a sense of loss (of history, of relevance, of the next generation) and in equal parts, an urgency for the future to define itself one way or other. The stories that couldn’t work anywhere else are involved with that dilemma, and here I’d include the MFPD stories, dealing with past and future, facing change at a mind boggling rate.

How did you settle on the title for the book?

When I lived in South Carolina, I listened to a lot of blues. That sense of loss, of irrelevance, of losing the next generation seemed really strong in the culture around me, in both the white and African-American communities. The New South happened, for better or worse, and the blues lived on. Contrast that with growing up in Nebraska, where nobody I knew (with one or two exceptions) listened to black music. But the music they did listen to, the old country and gospel tunes, were and are well-informed by the same human emotions. So blues just seemed to fit.

Talk about the creative decisions that went into choosing the cover.

Two words. Label tape. One day it just showed up everywhere on farm machinery and pickup dashboards. It went away just as fast, but not before becoming an icon for me, the definition of DIY rural America.

Which of these stories would you consider expanding into a novel?

Novel-wise there’s no competition for the title story, “Meadows Ford Blues.” This was called “Rock and Roll Woman” right up until the final epub files, but took the title spot because it evokes everything I was trying to say with the other stories: the small town sense of family-community, the change and loss, hedonistic nostalgia.

I think MFPD Chief Lyle is a guy who’s ended up cutting off parts of himself in order to stay at home and carry on some kind of imagined tradition. There’s still a lot to explore there with him and his friends. Why do they stay? Why is Jennifer there? How do they confront the ever-encroaching outside world?

Which of them would you like to see made into a movie or TV series?

The MFPD stories. Small town Nebraska has a never-ending pool of interesting characters and situations.

Many of these stories take place in cold weather or snow. Any reason for that?

In my memories it’s always winter in Nebraska. When I grew up on the farm, winter complicated everyday life in unbelievable ways. Blizzards would come and go, knocking out the phone or lights literally for days. Digging through drifts to get to the road, thawing out stock tanks and drinkers, pushing on with chores into the early night time darkness: these things I remember vividly.

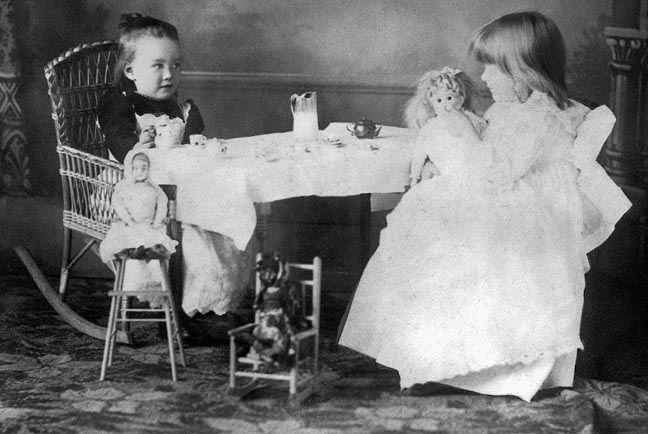

But there are some good memories too, like the wintertime Saturday showings at the little Star movie theater, or shopping for comics and paperbacks late at night because all the stores stayed open. Those times were magic.

You use dialogue and body language vividly to realize many of your characters. Chester Dokes, the title character of the last story, is an example. Talk about how a character like that comes to be for you.

I try to listen a lot to the way people actually talk, to watch the way they really move around –as opposed to the way they appear in TV and movies. As an only child I spent countless hours sitting around waiting for the grown-ups to stop talking. I’d lose track of what they were saying, but not how. Characters like Chester or the men in “Jolly’s Boy” are amalgamations of voices from that past.

You also write western stories set in this same part of Nebraska. Is the creative experience the same for both kinds of story or very different for you?

I told Matt Pizzolato that westerns, for me, are often about the dictates of geography. That’s still the case when I write about contemporary small town Nebraska. It’s hard to believe people still live in a place where, if you crave a Big Mac, you have to drive an hour to get one. But yes, the creative process is the same.

What do you learn from your readers?

I’ve learned to focus. During the past twenty years, I’ve written everything from corporate style guides to romance confessionals to cheesy biographies for kids. Turning to adult fiction, I’ve struggled to stay on topic, maybe on-brand is a better way to put it. But the readers help you do that. Without you guys, I might be writing music reviews.

What can readers look for from you next?

I’ve got a standalone western novella set again in Nebraska to epublish early this summer. And there’s another dozen or so short stories here. Some will see the light of day one way or another before Christmas.

Anything you would like to add that we didn’t cover?

I’m grateful you didn’t venture into digital versus traditional publishing. I’m touching on it here only to say that I think too many good writers are burning daylight over the topic. It is what it is. At the end of the day, how it gets out isn’t as important as what you have to say.

Thanks, Richard, for being here today. Every success.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Coming up: Elisabeth Higgins, Out of the West (1902)