|

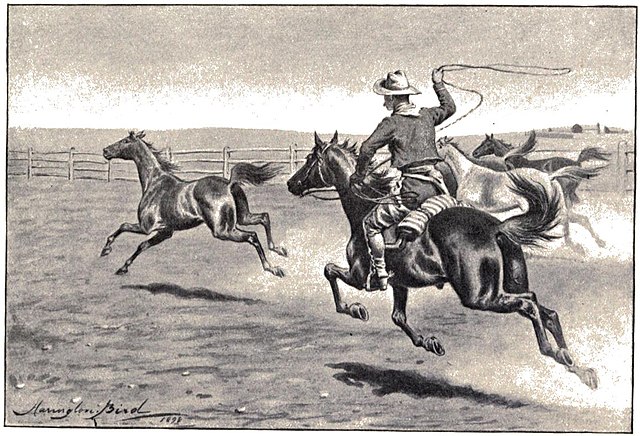

| Cowboy, 1898 |

The cowboy western originated with the dime novels of the nineteenth century. These were exaggerated tales of adventure in the Wild West. But when did cowboys first appear in mainstream popular fiction?

Vaqueros. In early examples, set in California, they

appear as vaqueros, and remind us that the actual horsemen who herded cattle in the frontier West were itinerant agricultural laborers. In Maria

Amparo Ruiz de Burton’s The Squatter and the Don (1885), a californio ranch owner has vaqueros among his employees.

They figure into the plot as a herd of cattle are driven through a winter storm

in the mountains above San Diego.

A foil to the central character of Gertrude Atherton’s Los

Cerritos (1890), Carlos Castro is the chief

vaquero at a neighboring ranch. He is a burly giant of a man, so full of energy

he is like a volcano waiting to erupt. His comrades adore him for his “enormous

vitality” and his “rude magnetism.” Though a horse thief, he is always acquitted

of any crime. He is opposed to americanos moving onto California rangeland, picks a fight with and

grievously wounds one of them, and sets fire to his ranch.

Ranch hands. English-speaking cowboys make an early appearance in Charles King’s Dunraven Ranch (1890). They are employed on a mysterious ranch

located near a cavalry outpost in Texas. Eager to solve the mystery, a young lieutenant

pays a call with several troopers, who are of Irish descent. The visit develops

into a donnybrook between the cavalrymen and the ranch hands, who are English.

Three ranch hands are minor characters in Marah Ellis Ryan’s

Told in the Hills (1890), set in western

Montana. Jim the youngest is an innocent, who gets excited when the cavalry

arrives to set up camp near the ranch. Another, Andrews, is occasionally sent

to the nearest settlement for the mail, but tends to stay overlong and come

home drunk.

Cowboys are a “wild combustible element” in Arthur

Paterson’s A Better Man (1890). They

gather in numbers in the saloon of a New Mexico frontier settlement. Some are

given to drunkenness and insulting women. The novel’s central character, a

rancher, assembles a small army of them to ride all day and night to rescue an

innocent man, who has been found guilty in a hurried trial and sentenced to be

hanged.

Cowboys. Owen Wister

may have popularized the cowboy, but in his early western stories written for Harper’s

and collected in Red Men and White (1896), they are dubious characters. Two crop up in “A Pilgrim on the Gila.”

The story’s narrator learns that one of them is avoiding a woman who is two

months shy of claiming him as a common-law husband. Later, the two cowboys are

among a dozen road agents who hold up an army paymaster and make off with the

strongbox.

|

| The Great K&A Train Robbery |

The cowboys in Paul Leicester Ford’s The Great K&A

Train Robbery (1897) talk in stereotypical

lingo. Asked if he is carrying a weapon, one responds, “Do I chaw terbaccy?”

Threatening another man, one calls him a “stinkin’ coyote” and tells him to

stay put “or I’ll blow yer so full of lead that yer couldn’t float in Salt

Lake.”

Colorful, yes, also ungovernable and potentially dangerous.

They are frequenters of saloons, eager to accept a wild rumor as fact, and

quick to rush a suspected wrongdoer to justice. Believing the young hero of the

novel to be a train robber, they try to lynch him from a telegraph pole.

Cowboys of a similar stripe appear in two of Cy Warman’s Frontier

Stories (1897). Given to gunplay and

playful troublemaking, they can easily find themselves on the wrong side of the

law. In one of them, several cowboys play a trick on a band of Indian cattle

thieves. Finding the cremated remains of one of them, they leave a handwritten

curse in the man’s skull that frightens the thieves away.

Warman’s “A Cowboy’s Funeral” starts out with some hijinks of a

half-dozen cowboys, who have ridden 200 miles to a town in Utah to mail a

letter. They get drunk and start firing their pistols until a bystander is

accidentally shot and killed. They make a hasty retreat into the desert, but

when the sheriff gives chase, one of them is shot dead.

When the cowboys put enough distance between themselves and

the law, they stop and make camp. There they pass the bottle before eventually

putting the dead man into a grave. One cowboy leads them in a version of “The

Streets of Laredo,” which the narrator describes as “plaintive and pleading—a

sort of mixture of negro minstrel and the old time Methodist revival song.”

Alfred Henry Lewis’ stories set in a fictional Arizona settlement, Wolfville, began as a series of newspaper sketches in 1890. In the first collection of them, Wolfville (1897), there are several who cowboy for a living. Their cattle do not much occupy them, except at spring roundup, when the men leave town to brand calves. One of these stories gives an account of Jaybird Bob, who gets shot dead for playing one too many practical jokes on a tenderfoot.

There is some mention of cowboys in Gwendolen Overton’s The

Heritage of Unrest (1901). When they

appear, they are likely to be “armed to the teeth” and a little dangerous. One

of them takes exception to a minister in a top hat and shoots at the lemon

sodas he orders in a saloon, the second time putting a bullet through the man’s

wrist.

There is some mention of cowboys in Gwendolen Overton’s The

Heritage of Unrest (1901). When they

appear, they are likely to be “armed to the teeth” and a little dangerous. One

of them takes exception to a minister in a top hat and shoots at the lemon

sodas he orders in a saloon, the second time putting a bullet through the man’s

wrist.

A nuisance to telegraphy, Overton notes, cowboys are given

to testing their marksmanship by shooting the insulators on telegraph poles.

Little more than a no-account drifter between occupations, the cowboy is

regarded as “vagrant and unsettled.”

Cowboys as

characters. One of the first full-fledged cowboy characters appears in Emma Ghent Curtis’ feminist novel The Fate of a Fool (1888). Set in Colorado, the story concerns a woman who is unhappily married.

The cowboy in the story, Frank Hutton, fits the stereotype: “I cuss and

drink and gamble and swear and carouse,” he admits, but he is not proud of the

fact. A frequenter of brothels from an early age, he has known poor health and fathered

a child out of wedlock. Wanting to reform, at the age of 29, he marries the

child’s mother and makes a home for both of them.

Marcus, one of Frank Norris’

characters in McTeague (1899), leaves San Francisco to become a cowboy in Southern California. There we find him “booted,

sombreroed, and revolvered, passing his days in the saddle and the better part

of his nights around the poker tables” in the saloons. Under the influence of

western dime novels, he’s proud to have lost two fingers in a gunfight.

Cowboy heroes. The

cowboy begins to take on the dimensions of a hero in Owen Wister’s Lin

McLean (1897). Wister casts McLean as a hard-working, fun-loving

“cowpuncher” on the Wyoming prairie, with maybe some bad habits and given to

the excesses of youth. Impulsive and not good at considering consequences, he

meets and marries a railroad restaurant waitress, or “biscuit shooter.” It’s a

bad match, and he soon repents his decision. Then he is saved by the discovery

that she’s already married to another man.

Cowboy heroes. The

cowboy begins to take on the dimensions of a hero in Owen Wister’s Lin

McLean (1897). Wister casts McLean as a hard-working, fun-loving

“cowpuncher” on the Wyoming prairie, with maybe some bad habits and given to

the excesses of youth. Impulsive and not good at considering consequences, he

meets and marries a railroad restaurant waitress, or “biscuit shooter.” It’s a

bad match, and he soon repents his decision. Then he is saved by the discovery

that she’s already married to another man.

Spending a lonely Christmas in Denver, he meets a bootblack,

Billy, who is a runaway from an abusive home. Concerned for the boy, he takes

him along back to Wyoming. The arrival of a pretty girl from Kentucky has

McLean considering marriage again. By novel’s end, the three of them are

becoming a family.

In Ralph Connor’s The Sky Pilot (1899), a novel set in Canada, we find a small

fraternity of men known as the Noble Seven, many of them remittance men. Among

them is a top-hand cowboy, Bronco Bill. Physically, he is true to type. He

moves with the “slow, careless indifference of a man sure of his position and

sure of his ability to maintain it.”

When the cowboys start making suggestive comments about a

young woman, he quickly scolds them for their disrespect. During a fund

drive to raise money for a church, he cleverly maneuvers a miserly Scotsman

into a wager that nets the church $700.

|

| Emerson Mead |

In Florence Finch Kelly’s With Hoops of Steel (1900), a young New Mexico rancher takes up a fight

against big rancher trying to grab up all of the range for himself. A man of

his word, Emerson Mead faces a murder trial rather than attempt to escape prosecution

for a crime he didn’t commit. Brave and confident almost to a fault, he freely

appears before a lynch mob to show that as an innocent man he has nothing to

fear.

A mutual respect for other men like himself keeps him from

yielding to the capitalist practices of moneyed interests who are taking over

the cattle industry and willfully destroying a way of life. His respect for

women also marks him as a man of some moral caliber.

The cowboy is cast as a romantic hero in Mary Etta Stickney’s

Brown of Lost River (1900). Working on a

ranch in Colorado, he is both handsome and an expert horseman. One rancher says

of Brown, “he’s every inch a man.” His employer agrees, “The fellow is simply a

perfect specimen of the human animal.”

When he falls in love with the pretty sister of the rancher’s

owner, she is too class conscious to consider him as more than a friend. But

against her will, she gradually gives in to feelings of attraction. It

helps that he has a Harvard education.

Wrapping up. The

year 1902 saw the publication of Wister’s The Virginian, a hugely

successful bestseller. That same year saw Frances McElrath’s The Rustler, in which a top-hand cowboy and ranch foreman

becomes a cattle thief and kidnaps a woman who has rejected him. Both novels were inspired by Wyoming’s Johnson County War.

Wrapping up. The

year 1902 saw the publication of Wister’s The Virginian, a hugely

successful bestseller. That same year saw Frances McElrath’s The Rustler, in which a top-hand cowboy and ranch foreman

becomes a cattle thief and kidnaps a woman who has rejected him. Both novels were inspired by Wyoming’s Johnson County War.The year also saw Henry Wallace Phillips’ Red Saunders, a collection of stories about an amiable, big-hearted, red-haired cowboy from the plains of North Dakota, with a fully developed sense of humor and a wry wit. He would appear again in two more collections of stories and a novel.

Over a period of two decades, the cowboy had evolved from a

minor but often troublesome character given to violence and gunplay. With the

turn of the century, he had become the central figure in stories of western

romance and adventure. In the following decades, a genre of frontier fiction,

the cowboy western, would evolve and flourish around him.

Image credit:

Book covers and illustrations from the novels

Drawing, John Alexander Harrington Bird (1846-1936), Wikimedia Commons

Coming up: Arthur Henry Paterson, The Better Man (1890)

Interesting early history of the genre. Thanks! I've been reading some early dime novels from my collection lately. While most aren't exactly what I'd call well-written, they are entertaining and give insight to bygone days. I'll have to look up some of these more serious attempts at literature.

ReplyDeleteI didn't know the Great K&K was a novel. I have the Tom Mix movie, whicj I found quite entertaining.

Ron, thanks for a timely and a terrific post. Timely because only last Sunday I bought an illustrated book about cowboys titled "The Old West: The Cowboys" published by Time-Life Books in 1973. It is a detailed pictorial history of the American cowboy whose high time, according to the book, "lasted a bare generation, from the end of the Civil War until the mid-1880s, when bad weather, poor range management and disaster cattle-market prices forced an end to the old freewheeling ways." It has some fantastic colour and black-and-white paintings and photographs of cowboys in action as well as drawings of a cowboy's attire. I didn't know they were called vaqueros derived from a Spanish word and influenced by Spanish California. I have just started reading the book and your narrative of early frontier fiction is going to add to the excitement of reading about this historical period in America.

ReplyDeleteYou got yourself a good reference book that should be full of good images. I believe that series was pretty dependable for historical information, too.

ReplyDeleteThere were two streams of cowboy traditions, the Texas cowboys, who learned about open-range cattle herding from the Mexican vaqueros. Then there were the California and Great Basin cowboys who preserved more of the style of their Mexican predecessors, especially in garb and gear. They came to be called "buckaroos," a corruption of "vaquero."

Ron, it is a good reference book and the Time-Life editors have credited dozens of writers and researchers as well as historical museums and societies for all the information it contains. Many of the books in the bibliography should be in public domain. I hope to write about the book soon, at least as soon as I get the essence of it.

ReplyDeleteMama don't let your babies grow up to be cowboys. :)

ReplyDelete