This is a kill-or-be-killed western with a very high body count. Something like 20 named characters die in one way or another, plus a lot of hostile Indians and all but

one of a troop of cavalrymen. Death comes in various ways, including fever,

infection, torture, and a grizzly attack. There are also flashbacks to Civil

War battlefields, carnage, and hand-to-hand combat.

The central

character is a veteran of that war. Having served as a young Confederate

colonel, he is too much his own man to endure taking orders and dealing with

fools in uniform. Along with the occasional PTSD-influenced dream, he has been

deeply affected by the war. He has learned more than a few survival skills, as

well as a coldly business-like way of distancing himself from death. You are a

hard man, someone tells him.

Plot. McKay takes a job on the frontier for the U.S.

cavalry, chasing down a gunrunner who has been selling war-surplus repeating

rifles to the Sioux. His pursuit takes him across the plains from Omaha to

Montana, then south to Missouri. Associated with him along the way are a

settler and his wife, a mountain man, an Indian, and a former slave. Given the

high-risk nature of McKay’s mission, only one of them survives.

The narrative shifts

between pursuer and pursued. The gunrunner is an unpleasant man named Wild

Bill. More than half afraid of the Sioux, he keeps them suitably intimidated by

demonstrating the killing power of a Gatling gun. When they see it used to wipe

out a bunch of mounted blucoats, the Sioux would love to get their hands on one

themselves.

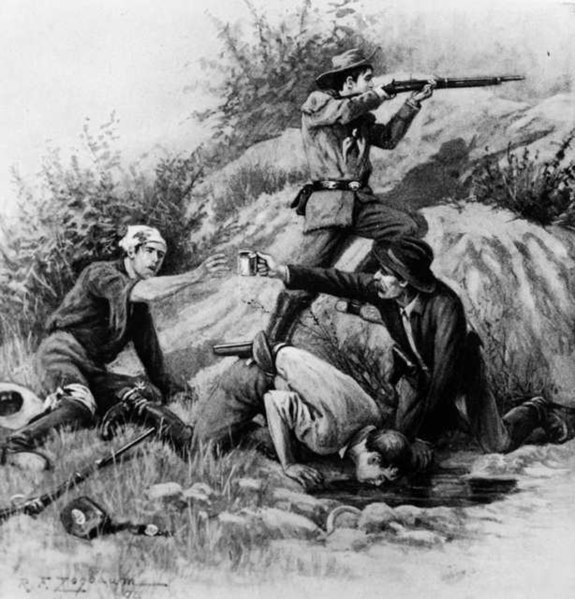

.jpg) |

| U. S. Cavalry, 1868 |

Character. McKay makes for an interesting blend of

frontier ethics. On the one hand, he is a survivalist. He knows how to treat

wounds, fevers, and snakebites, and he repeatedly advocates tireless vigilance

in the face of threats to life. Out here, he advises, you have to protect

yourself and family. Keep a gun handy, eyes open, and shoot to kill.

Meanwhile, he has a

live-and-let-live philosophy. He wastes no time dwelling on the past and bears

no grudges about the war. The Union was better organized and its troops better

supplied. End of story. Bury the dead and move on. He judges another man’s

worth regardless of race, creed, or color. Thus he counts Indians and a former

slave among the men he trusts.

Rarely moved to

emotion, he admits at one point that it hurts him to bury women and children.

And he laments the deaths of soldiers whose last days and whereabouts will

never be known by their loved ones. But dead colleagues who have risked danger

and fought side-by-side with him are buried with a few dry-eyed words said over

their graves. Period. No grief.

Women. McKay, we are told, is not used to being around

“womenfolk,” and they rarely appear in the story. Only one commands his

respect. She is tough and fearless, ready with a gun, determined to make good

on the frontier. But even with that strong hand, she is unable to stay in the

game.

|

| U. S. Cavalry, 1868 |

His only attachment

is to a young girl, for whom he buys candy. She has lost both parents and

foster parents, and McKay has promised to be her guardian. He would prefer to

be responsible only to himself, he says earlier in the novel, but he’s “not

that kind of man.”

Caveats. This novel is not for everyone. Readers will

enjoy it who (a) don’t care strongly about historical or geographic accuracy,

(b) aren’t put off by gruesomely graphic descriptions of torture and death, (c)

don’t mind a slower pace that allows for digressions and stories within

stories, and (d) don’t care whether characters speak in a modern-day

vernacular.

A firmer editorial

hand would have shortened this novel by 10% or more. Especially in the latter

half, when cutting to the chase would be more effective, the narrative tends to

get talky. Repetition is also a distraction. As one example, characters make an

unusual number of references to the human posterior. The search function on

kindle makes it easy to count them. The word “ass” crops up in conversation 47

times, “butt” 15 times, “rear” nine, “backside” seven, and “buns” once.

Wrapping up. Readers interested in survival skills will find

this novel of interest, and a glance at the author’s bio reveals that Benton is

well schooled in that discipline. As a veteran of many years active duty, he

also creates a believably realistic portrayal of a military setting, from

fumbling fresh recruits to commanding officers of various temperaments and

degrees of competence.

James McKay, U.

S. Army Scout was first

published in 2008, and the kindle edition was released in 2013.

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

Coming up: Quigley Down Under (1990)

well I tend to enjoy a high body count so this sounds interesting to me.

ReplyDeleteRon, the character of James McKay reminds me somewhat of the main character in Ed Gorman's "Cavalry Man: The Killing Machine," a Union investigator who goes in search of a Gatling gun stolen from the army. I wouldn't mind reading this novel in spite of the caveats; in fact, I want to read some modern-day westerns.

ReplyDeleteSounds like another "Edge" novel, i might read it?

ReplyDeleteHigh body counts usually indicate a badly written book, especially if the victims are nameless and not developed characters, so no reader cares about their deaths. Compare that to Shane, where the main characters are richly drawn, and the reader cares deeply about their survival.

ReplyDeleteCould not agree more.

Delete