There’s surely as much western frontier north of the 49th parallel as there is south, and Canada has had numerous writers setting their stories there. During the years

1880-1915, a dozen or more of them appeared to write from the mountains and timberland of BC, to the prairie, the border country

straddling the international boundary with Montana, all the way to the frozen Yukon.

|

| Ralph Connor |

Ralph Connor

was the pen name of Charles William Gordon (1860–1937), a Presbyterian minister

of some prominence in Canada. The Sky

Pilot (1899) was the novel that made him

famous, selling over a million copies. It is set in a frontier community, Swan

Creek, in the foothills of the Rockies, west of Calgary.

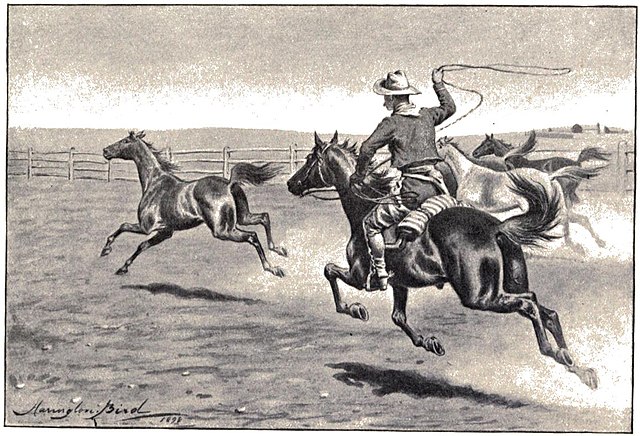

Its characters are early settlers, ranchers, and cowboys,

and at the center of them is a church missionary, Arthur Wellington Moore, who

has been dubbed “the sky pilot.” Connor served 40 years as a minister at a

single parish in Winnipeg, Manitoba. In 1972 his Works, containing 43 titles, were published by the National

Library of Canada.

Bertrand Sinclair

(1881-1972) was born in Scotland and came to North America in 1889. He was a

young cowpuncher living in Montana when he wrote Raw Gold (1908)

set north of the border in the southern corners of what is now Alberta and

Saskatchewan.

The time is shortly after the arrival of the North-West Mounted

Police, and the entire story takes place within one or two days’ riding of Fort

Walsh in the Cypress Hills. We get the wide-open frontier of the 1870s with outlaws and

lawmen, stolen money, and an innocent fugitive wrongly accused of a crime.

After a brief marriage to western writer B. M. Bower, Sinclair settled in

British Columbia, where he continued to write.

.jpg)

.jpg/256px-The_Widow_(Boston_Public_Library).jpg)

.jpg/613px-Sauromalus_varius_(3).jpg)

.jpg)