This is an as-told-to memoir of the early years of a cowboy who was born in England and grew up in Nebraska. E. C. "Teddy Blue" Abbott (1860-1939) drove cattle along the western trails into Montana, eventually settling there, and worked for several cattle owners, all during the 1870s and 1880s.

His story covers that brief period of time when the West was open range, before settlers began putting up fences. It's a story told in the 1930s by an old man to a woman from the East, Helena Huntington Smith, who had the presence of mind to capture his life in the printed word before his generation had passed completely.

Teddy Blue, as he was called, was something of a rip-tearer in his youth, living up to the wilder stereotype of rangeland cowboys, by his own account. On the one hand, there is the fierce recklessness of herding cattle, which through accident and various mishaps took the lives of many young men. And then there is his life in town, befriending prostitutes, drinking hard, shooting up saloons, and on occasion riding his horse indoors.

His favorite job is working as a "rep" for cattle-owners, going to the regular roundups where cattle were sorted and branded, requiring him to retain a vast knowledge of brands used on the range and other markings. For a while, he works for stockman Granville Stuart, who headed up a vigilante effort that significantly reduced the number of active cattle rustlers in Montana. Stuart eventually becomes Abbott's reluctant father-in-law, after the young penniless cowboy takes a shine to one of his daughters.

The book rambles back and forth in time as Abbott more or less free-associates for Smith. And while scholars may question the accuracy of his memory at points, he was easily one of the more widely known figures of the old West for his personality and antics, not to mention having befriended the likes of cowboy artist and writer Charlie Russell, as well as Calamity Jane. He even crossed paths with Teddy Roosevelt.

His story makes an enjoyable read and evokes with feeling those early "innocent" days of an adventurous youth lived when the West was young as he was. His admiration for the Cheyenne Indians is, he admits, unusual for a white man of the times. And though they were both the best and worst of times (e.g., the crippling winter of 1886-87), he shares with Charlie Russell a nostalgic belief that they were the good old days, the likes of which haven't been seen since.

A classic cowboy memoir, full of stories and yarns, social history, frontier customs and mores that make that time come alive with an immediacy and intimacy that are seldom found in records of the period.

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

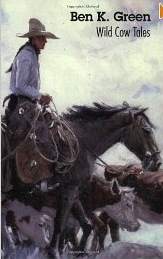

Ben K. Green, Wild Cow Tales

Today I'm beginning a series of what I'm calling cowboy memoirs. These are books written by or about cowboys describing their lives and their work. This is one of several by Texas writer Ben K. Green (1912-1974), who in the later years of his life wrote of his experiences in much younger days. Wild Cow Tales was published in 1967.

Wild cows, as he explains, are just plain ornery, uncooperative cattle that resist all efforts to be rounded up. As a young Texas cowboy in the 1920s and 30s, Green made a living going after these hard-to-catch cattle, and this book is a collection of accounts of his successes (if he ever missed any, he doesn't mention it).

Usually he works alone, on horseback, gathering up cows a few at a time and driving them to the nearest train station where they can be shipped to market. Typically he has worked a deal with the owner, buying them "range delivery," and spending sometimes many weeks to outsmart the critters, often one by one, to get them roped, corralled, or whatever it takes.

A young, tough, wild cowboy, as he often refers to himself, he has more than his share of hot, sweaty work, getting bunged up, frustrated, and frequently outmaneuvered. On one job, he's also shunned by a whole community of folk who regard him with disdain as he works to gather up a herd of cows for a bank collecting a bad debt. Each account is different, presenting a very different situation, and Green takes the reader along as he mulls over the problem, tries this and then that, eventually finding a solution.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It's a departure from other books about cowboying, and it gets very much into cowboy psychology and the wealth of knowledge acquired in dealing daily with cattle. Green writes in a conversational style, with dry humor and a leisurely way of setting scenes and describing action, meanwhile building a kind of suspense as he figures out each time how to outsmart his "wild cows."

Thanks to the University of Nebraska Press for reprinting this and many other classics of western literature. Western illustrator Lorence Bjorklund provides many fine drawings, and with the cover design from a painting by W.H.D. Koerner they nicely capture the spirit of this book.

Coming up: Charles Alden Seltzer, The Coming of the Law (1912)

Wild cows, as he explains, are just plain ornery, uncooperative cattle that resist all efforts to be rounded up. As a young Texas cowboy in the 1920s and 30s, Green made a living going after these hard-to-catch cattle, and this book is a collection of accounts of his successes (if he ever missed any, he doesn't mention it).

Usually he works alone, on horseback, gathering up cows a few at a time and driving them to the nearest train station where they can be shipped to market. Typically he has worked a deal with the owner, buying them "range delivery," and spending sometimes many weeks to outsmart the critters, often one by one, to get them roped, corralled, or whatever it takes.

A young, tough, wild cowboy, as he often refers to himself, he has more than his share of hot, sweaty work, getting bunged up, frustrated, and frequently outmaneuvered. On one job, he's also shunned by a whole community of folk who regard him with disdain as he works to gather up a herd of cows for a bank collecting a bad debt. Each account is different, presenting a very different situation, and Green takes the reader along as he mulls over the problem, tries this and then that, eventually finding a solution.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It's a departure from other books about cowboying, and it gets very much into cowboy psychology and the wealth of knowledge acquired in dealing daily with cattle. Green writes in a conversational style, with dry humor and a leisurely way of setting scenes and describing action, meanwhile building a kind of suspense as he figures out each time how to outsmart his "wild cows."

Thanks to the University of Nebraska Press for reprinting this and many other classics of western literature. Western illustrator Lorence Bjorklund provides many fine drawings, and with the cover design from a painting by W.H.D. Koerner they nicely capture the spirit of this book.

Coming up: Charles Alden Seltzer, The Coming of the Law (1912)

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Book: The Westerners (1901)

While the title of this novel has “cowboy” written all over it, not a single man of that breed appears between its covers. The Westerners was Stewart Edward White’s first novel. Before publication as a book by Grosset & Dunlap, it was serialized in eight parts in The Junior Munsey in 1900-1901.

|

| 1901 edition |

White was all of 26 years old at the time, and it shows. The book is more interested in character and relationships than story, and it probably should have been the other way around. Still, the central plot when told in a few paragraphs shows promise.

The story. The setting is the Dakota Territory of the Old West, and it takes place mostly in a mining camp called Copper Creek in the Black Hills. A half-breed by the name of Lafond has a hate on for a white man, Billy Knapp, that goes back 20-plus years. Because of Lafond’s mixed race, Knapp once refused to let him join a wagon train.

After that long-ago incident, we learn that Lafond “went native” for a while, joining a hostile band of Sioux. Then after the Battle of Little Bighorn – in which Lafond kills Custer (now you know) – he became a successful entrepreneur in the white man’s world. He has built a saloon and dancehall franchise, setting up wherever there are mining camps.

He finds Knapp, a prospector in Copper Creek, and hatches a scheme to bring the man down. A trio of venture capitalists from Chicago gives Knapp a bundle of money to develop a proper mine, and like a dot com startup, he overspends and goes bust. Meanwhile, Lafond has worked out a deal with the investors to take ownership of the mine for himself.

Knapp loses everything and is supposed to leave town a broken man. But he is too tough to break. Instead, he rides off into the sunset with a prospector buddy from younger days who has made a fortune in Wyoming.

Lafond meets his end when he is captured by the Sioux tribe he deserted all those years before. They hold a tribunal during which he is found guilty of a crime he didn’t actually commit. Some irony there. And he is tortured to death. (Yeah, you read that right.)

|

| Mining camp, 1890 |

What I left out. This actually gets interesting, because White creates a female character who dominates much of the novel – something we haven’t seen much of. There’s B. M. Bower’s ranch romance, Chip of the Flying U, which comes along six years later, but this is no ranch romance. It would not even qualify as a love story.

Molly is a young woman who believes Lafond is her father. She doesn’t know that he not only kidnapped her as a toddler but killed and scalped her real mother in an Indian raid. (Yeah, you read that right, too.) Raised by a white family, she is pretty, smart, and adventurous. Lafond brings her to Copper Creek.

There she is the first woman in camp and becomes the center of every man’s attention and a favorite. She discovers she has a natural talent for manipulating men and gets involved with two of them: Jack Graham, a thoughtful book-reader who respects her, and Cheyenne Harry, who does not.

She tires of discussing philosophy with Graham and “loses her reputation” by hooking up with Harry. The villainous Lafond delights in this development, apparently out of sheer meanness. When a shameless dancehall queen in the form of Bismarck Anne (cf. Calamity Jane) shows up in Copper Creek, Molly sees what fate has in store for her as a good-time girl and fallen woman.

Riddled by humiliation and in the grip of hysteria, she wants to commit suicide by jumping off a cliff. Graham, decent man that he is, saves her from that, and when she regains her wits, she declares, “I will go with you, Jack, forever, to the end of the world.”

Labels:

book review,

dakota,

stewart edward white,

western fiction

Monday, September 27, 2010

Republic Pictures 75th Anniversary, part 2

OK, today is the second installment of my day at the Republic Pictures Anniversary at CBS Studios over in Studio City, California. A few more photos this time, and maybe a little less talk. First a logo:

There were two performance areas, each with singers and musicians from the Western Music Association. Here are Jason "Buck" Corbett and some of the boys:

A number of those present were in period costumes. Here's a guy taking advantage of a photo op with someone who could have just walked out of the Longbranch Saloon. Notice how she thoughtfully uses her fan to cover his midrift.

It was a work day at the studios, and over on Mary Tyler Moore Avenue, in the shadow of the sound stages, a piece of scenery was on the move:

Over on St. Elsewhere Street, there was a big room filled with autograph tables and people gathering around old movie actors or their descendants. Here an elderly celebrity in cowboy outfit and six-gun was entertaining a gathering of fans.

At the corner of St. Elsewhere and Mack Sennett Avenue, Nudie had parked his Bonneville. It gleamed in the sun. Notice the horseshoes and revolvers over the headlights. Behind is a little covered wagon with costumes made for Roy Rogers and Dale Evans.

Here's the commissary where Laurie and I braved the hungry hordes for burgers and fries. This guy had the grill fired up like a flame thrower. Notice the misters overhead.

A bunch of folks from as far away as Maryland were together at a table of Roy Rogers fans, including these look-alikes of Gabby Hayes and a latter day Dale Evans.

Back on Gunsmoke Ave, a gang in period garb (except for the one on the left, who's from another period) were gathered for a group photo. The ones in the black hats had been lingering in the shade of a tree most of the day and from a distance looked like a congregation of Wyatt Earps.

The guy in front with the six-shooter was doing a dance to a rap song as I arrived in the morning. It gave an anything-goes twist to the spirit of the day. Anyway, Republic Pictures wasn't exactly known for its high seriousness. On the way out, I found John Bergstrom closing out a set of his songs. Here he is singing "Throw Down the Box" from his new CD.

It's a fine little song with a refrain that recalls a line from countless B-westerns with stage hold-ups. The sentiment in the song was authentic, by the way, and so were the straw bales in the foreground.

Thanks for coming along.

Coming up: Stewart Edward White's The Westerners (1901)

There were two performance areas, each with singers and musicians from the Western Music Association. Here are Jason "Buck" Corbett and some of the boys:

|

| Jason "Buck" Corbett |

|

| Photo op with a Miss Kitty |

|

| Here it is coming . . . |

|

| There it is going . . . |

|

| Autograph hunters |

|

| Nudie's Bonneville |

| ||

| The grill cook assembling Laurie's burger |

|

| Roy Rogers fans |

|

| Ready to put the wild back in Wild West |

|

| John Bergstrom singing his western songs |

Thanks for coming along.

Coming up: Stewart Edward White's The Westerners (1901)

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Republic Pictures 75th Anniversary

This is a special edition of Buddies in the Saddle with pictures from a day at the Republic Pictures 75th Anniversary at CBS Studios in Studio City, California. Studio City is a short hop over the Sepulveda Pass to the San Fernando Valley from where I live on the Westside. (Short hop, that is, if the traffic is moving on the 405 and 101 freeways.)

It's a big operation covering an area of many city blocks. It's located in a residential neighborhood and bounded by the Los Angeles "River" on one side and busy Ventura Boulevard on another, where Laurel Canyon comes down out of the Santa Monica Mountains.

Inside the gates, there are huge sound stages and a small cluster of tree-lined streets with names like My Three Sons (see map). Someone with a knowledge of movie history could probably tell you what movies and TV series the houses there have appeared in.

I arrived not long after 11:00 a.m. when the gates opened. By that time there was already a long line waiting to get through security. It could have been LAX, but few people had any "carry-on" so it wasn't a long wait. People, many of them, came dressed for the occasion in cowboy hats and western gear. Emerging from the parking garage, we found ourselves on Gunsmoke Avenue, where the vendors were lined up.

It may look like a warm southern California morning, but it was actually already hot. We're currently in the midst of socal's version of Indian summer - triple-digit highs. Walking on I found one of the several outdoor demos. This is stuntman and horse trainer Jay Rockwell and one of his horses, Bodie.

Jay and his wife Maria (who, they say, met on the set of Deadwood) run Hollywood Trick Horses. Next up the way was a trick gunslinger, Joey Dillon, with a routine that had a big crowd laughing and applauding. Clearly an example of someone who as a young man had too much time on his hands. (See Bobbie's comment below for more info about him.)

The banner across the back of the photo is for the Museum of the San Fernando Valley, one of the sponsors of the event. Incorporated in 2005, the museum has set for itself an energetic objective, to preserve the culture of a geographical area with a population that would make it the fifth largest city in the U.S. - if it were not already part of another city, Los Angeles.

Opposite the performance areas were several structures looking like houses in Anytown, USA. Here a security guard is stationed to discourage visitors from looking inside for one of their favorite TV families.

By now I'd begun finding people to talk to. A conversation started with Ed Boyle below who was putting on one of the finest pairs of high-top cowboy boots I'd seen in a long time. Calling himself, "just a cowboy," he spoke of growing up on a family ranch in southern California, riding rough stock in rodeos (where he knew Slim Pickens), and working in western movies as a cowboy extra.

Says he rarely had lines in Hollywood movies, but after being featured in a commericial shot in Spain, he is famous in Europe - now known there as Cash Cow Hank, who's learned that online investing is more profitable than rustling cattle. Here he is with his wife Jo, who runs a mobile western wear shop that sets up at events like this one.

Next door to them I found none other than Laurie Powers of Laurie's Wild West, who was sharing space in Bobbi Jean and Jim Bell's booth. Their western gear store Out West is located in Newhall, California, and they also have an online store. Here are Laurie and Bobbi.

Bobbi had some featured guests from the entertainment world, including these two guys, Troy Andrew Smith and John Bergstrom.

Troy is a western writer. His new book, Radersburg Gold, is set during the gold rush in Montana. He's from Acton, California, and you can find out more about him at his website. John Bergstrom is a western singer-composer from Saugus, California. He's with the Western Music Association, who also had a booth at the event. I got to hear John sing later in the day. He has a nice feel for the tradition of western song. Here's more about John.

Someone I knew from the movies was also at the Bell's Out West, actor Peter Sherayko. Here he is taking advantage of the shade and striking a pose with a cigar .

He was signing autographs on 8x10 glossies of himself as Texas Jack Vermillion in Tombstone. It's a wonderful performance in a great role, and I've read somewhere that much of the part was cut to reduce the film's length. Still very much involved in movie production, he runs his own company Caravan West. His website, by the way, is chock full of historical information about the Old West.

OK, that's probably enough for today. I'll finish up next time.

It's a big operation covering an area of many city blocks. It's located in a residential neighborhood and bounded by the Los Angeles "River" on one side and busy Ventura Boulevard on another, where Laurel Canyon comes down out of the Santa Monica Mountains.

Inside the gates, there are huge sound stages and a small cluster of tree-lined streets with names like My Three Sons (see map). Someone with a knowledge of movie history could probably tell you what movies and TV series the houses there have appeared in.

I arrived not long after 11:00 a.m. when the gates opened. By that time there was already a long line waiting to get through security. It could have been LAX, but few people had any "carry-on" so it wasn't a long wait. People, many of them, came dressed for the occasion in cowboy hats and western gear. Emerging from the parking garage, we found ourselves on Gunsmoke Avenue, where the vendors were lined up.

|

| Gunsmoke Avenue |

|

| Jay Rockwell and Bodie |

|

| Stand-up trick gunslinger |

Opposite the performance areas were several structures looking like houses in Anytown, USA. Here a security guard is stationed to discourage visitors from looking inside for one of their favorite TV families.

|

| All quiet on My Three Sons Avenue |

By now I'd begun finding people to talk to. A conversation started with Ed Boyle below who was putting on one of the finest pairs of high-top cowboy boots I'd seen in a long time. Calling himself, "just a cowboy," he spoke of growing up on a family ranch in southern California, riding rough stock in rodeos (where he knew Slim Pickens), and working in western movies as a cowboy extra.

Says he rarely had lines in Hollywood movies, but after being featured in a commericial shot in Spain, he is famous in Europe - now known there as Cash Cow Hank, who's learned that online investing is more profitable than rustling cattle. Here he is with his wife Jo, who runs a mobile western wear shop that sets up at events like this one.

|

| Jo Pavlina and Ed Boyle |

|

| Laurie Powers and Bobbi Jean Bell |

|

| Troy Andrew Smith and John Bergstrom |

Someone I knew from the movies was also at the Bell's Out West, actor Peter Sherayko. Here he is taking advantage of the shade and striking a pose with a cigar .

|

| Actor, Peter Sherayko |

OK, that's probably enough for today. I'll finish up next time.

Friday, September 24, 2010

First westerns: Cecil B. DeMille and John Ford

Let's wrap up the survey of the earliest western filmmakers with a look at two directors - Cecil B. DeMille and the young John Ford - and the cowboy actors who starred in their pictures: Dustin Farnum, Harry Carey, and Hoot Gibson.

|

| Cecil B. DeMille |

Jesse Lasky and Cecil B. DeMille. These two partners made the first feature-length western, The Squaw Man (1914), based on the Broadway play of the same name. It was their first picture, and they shot it working out of a barn on Vine Street in Hollywood.

It starred New York actor Dustin Farnum, who had gained fame in the lead role of another Broadway play, adapted from Owen Wister’s The Virginian. Here is a clip that comes about 20 minutes into The Squaw Man. Farnum is Bill Carston, an upper-class Englishman believed wrongly to have stolen money from a fund for orphans.

He comes to America and eventually finds his way out West, where he buys a ranch. In the opening scene below, he stops a pickpocket from robbing a man in an upscale New York café. Together the two new friends leave town, and we are quickly in the land of cowboys, cattle, saloons, and Indians.

The success of this film was quickly followed by Lasky and DeMille's filming of The Virginian (1914), with Dustin Farnum again in the lead role. The film version follows the stage version of the play, which eliminates the novel’s narrator and focuses on the key scenes.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Winter in the Blood - the Movie

|

| Northern Montana, near Havre. Photo by Matt Lavin |

The review. James Welch is probably Montana's foremost Native American writer, and this wonderful novella is evidence of his considerable talent. Published 36 years ago (1974), it takes place in the shadow that was cast by the nation's approaching bicentennial. While neither bitter nor angry, it manages anyway to portray a country that has little to show for itself but "greed and stupidity." The values the book embraces are finally those available to every American, native or otherwise - compassion and respect for life and the living.

The story concerns a few days in the life of a 32-year-old man, descendant of Indians and living in two worlds, his mother's home on the reservation and the dreary bars and hotels of nearby Havre and Malta, Montana. His days and nights blending together in an alcoholic haze, he meets a deranged white man, picks up women and gets punched in the nose.

Meanwhile, he is haunted by a past that includes the death of an older brother and an injury to his knee that multiple operations have not remedied. Out of these unpromising circumstances, Welch finds the beginnings of a kind of personal salvation. By reaching back through the memory of a blind old man's act of charity, he restores the younger man's vision of himself.

Among the ranks of modern Native American writers, such as Louise Erdrich, Welch opens up a world for non-Indian readers that goes well beyond the usual stereotypes. His Indians are strikingly individual, absorbed in the everyday, motivated as much by self-interest and cock-eyed notions as their white counterparts. In Welch's hands, a conversation among five of them can be as comic and absurd as Ionesco. Meanwhile, the Native American past is there to ground a person with a sense of purpose and identity. For all its sorrows, Welch's story is finally a joy to read.

Photo credit:

Photo of northern Montana, near Havre, wikimedia.org

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Book: Arizona Nights (1907)

Reaching way back again into EPH (Early Pulp History), I’m talking today about another western writer, Stewart Edward White (1873-1946). Arizona Nights was not his first book, but it’s said by some to be his best. His first novel was The Westerners (1901), which I plan to get to next.

|

| 1907 edition, cover by N.C.Wyeth |

White started out as a Midwesterner, growing up and getting his education in Michigan. But he spent time in Arizona in 1904 and eventually settled in California. Arizona Nights includes a novel-length story by the same name, plus two shorter stories published earlier in magazines. “The Rawhide” appeared in McClure’s in 1904, and “The Two-Gun Man” followed in Collier’s in 1905.

“Arizona Nights.” This is actually not a novel. It’s a bunch of campfire stories told by several cowboys who work together for a ranch owner in southeast Arizona. The stories are of various kinds, ranging from personal experiences to tall tales to a real pulp-style adventure.

Linking them together are descriptions of the Arizona desert, a couple of cloudbursts, a night spent out of the weather in a cave, and then a long, detailed description of an open range roundup. I’ve read several accounts of roundups, and this is one of the best, told from the point of view of an unnamed cowboy narrator. He captures the rhythm of the work and the feelings that go along with it – the excitement, the exertion, the exhaustion, the camaraderie.

|

| Stewart Edward White, 1912 |

“The Two-Gun Man.” This short story takes place in the same part of southeast Arizona, on the same ranch. Rustlers have been making off with cattle, but pursuit across Apache Territory and into Mexico is dangerous. The ranch owner sends his foreman to find someone willing to take the risk.

The foreman invents a novel way to find the man for the job. In a town full of desperados he challenges anyone there to a knife fight – the two of them holding a bandana between them in their teeth. (Only time I ever came across this before was in the movie The Long Riders.) The foreman then hires the first man who offers to fight him, and goes back to the ranch with the “two-gun man” of the title.

The man agrees, for a big reward, to return with the cattle and the man who took them. And after ten days, he shows up with the cattle, but no man. Then, drawing both guns, he takes the money and reveals that he’s the rustler who took them in the first place, and he is off into the night.

Labels:

arizona,

book review,

stewart edward white,

western fiction

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Four Faces West (1948)

This is the film based on Eugene Manlove Rhodes’ novel Pasó Por Aquí, first published in 1926. In that novel, a young man robs a storekeeper and while on the run finds a Mexican family dying of diphtheria in an isolated cabin. He nurses them back to health and is found there by Pat Garrett.

The film is an interesting example of how a story that originates in print is bent to fit the expectations of a Hollywood audience. You can begin with the title. It morphs from Spanish to English, and it’s not even an attempt at translation. Meanwhile, Four Faces West is a generic title that doesn’t fit the story. There are several possible combinations of four characters in the film, and they’re all heading south, not west.

The hero. Made today, the film would star a younger actor as the central character, Ross McEwen. Which would be a lot closer to what Rhodes had in mind. His McEwen has a young man’s impulsiveness and high-risk resourcefulness. He robs the storekeeper because he needs the money, but he throws it all away when the posse is about to nab him. That he has the moral integrity to stop and help this sick family has to come as a surprise.

Joel McCrae’s portrayal is more in keeping with a 1940s Hollywood cowboy stereotype. At 43, McCrae plays him as a sincere guy, down on his luck. He robs a bank to get a $2000 “loan” to send to his father. We are to recognize him as a basically good man driven to a desperate act. Later, when he wins money playing cards, he wants to begin repaying the “loan.”

The film’s outcome depends on whether he stops running from the law and turns himself in. This would prove that he’s not a coward and not a criminal. In Rhodes story, on the other hand, he’s already proven this by giving up his run for the border to save the Mexican family.

He has no further debt to pay society, and Pat Garrett as the moral center in the story, recognizes this. While the film ends with Garrett (Charles Bickford) taking McEwen into custody, the original story ends with the two men gathering firewood together and not acknowledging each other’s true identity. A nurse from the East learns that this is the way of the West.

Romance. Hollywood likes a love story, and the writers have injected one here. The nurse Jay (called Fay in the movie) who appears only at the beginning and end of Rhodes novel, becomes a central character in the screen version. She is played by Frances Dee, Joel McCrae’s wife in real life. Bitten by a rattlesnake before jumping on a train bound for El Paso, McEwen is treated by Fay. And the screenwriters have them travel to Alamogordo together.

Along the way, she gets to like him but begins to suspect that he is the man wanted for bank robbery. There’s a big reward out for his capture, dead or alive. In true Hollywood style, his attraction to her keeps him from hurrying on to safety in Mexico. He stops for a time in Alamogordo, but Pat Garrett and the rest of the posse eventually track him there.

Labels:

eugene manlove rhodes,

joel mccrae,

new mexico,

western movies,

westerns

Monday, September 20, 2010

Rex Beach, part 2

Last week I started talking about the short story collection Pardners (1906) by Rex Beach. It’s a mix of stories, some set in the West and some in Alaska, where Beach prospected for gold. I’m sticking with the western stories, since that’s been the focus here so far.

|

| Rex Beach, wearing a Stetson |

I actually don’t know whether Beach knew from experience the West he’s writing about. He spent his early and later years in Florida. We can wonder how much he was influenced by reading stories set in the West. Maybe I’ll find out more as I go along.

“The Shyness of Shorty.” This has to be a one-of-kind story. I’ll come back and change this if I ever find another one like it. The central character is a cowboy dwarf. No comic figure by a long shot, he has compensated for his height by being one tough son-of-a-gun.

Show any sign of amusement in his presence, and you’re looking down the barrel of one or both six-guns. He’s also physically strong and a fierce fighter, with the deepest voice of any man in the room. He is so rounded as a character and so not stereotypical, you have to believe Beach knew someone like him.

The story takes place at a roadside inn, where the innkeeper is friendly with a local gang of brigands. A new sheriff has sworn to bring the gang to justice, and as it happens all of the aforementioned characters converge the same night at the inn – including the sheriff’s new bride.

The bride, nonplussed by Shorty’s size, treats him with the kind regard she seems to have for every living thing. He is utterly disarmed by her and nearly unable to speak above a wheeze. Here at last is his Achilles heel.

Friday, September 17, 2010

First westerns: D. W. Griffith and Tom Mix

It's Friday again and time to continue our little survey of the first western movies. This time, two other major figures in Hollywood. One came from New York as a director with a long list of film credits. The other was a jack of various trades living in Oklahoma. By 1920, the first had already made the one great film he'd be remembered for. The other was on his way to becoming one of the biggest cowboy stars of all time.

D. W. Griffith.

|

| D. W. Griffith, c1925 |

The first is set in Dakota Territory and concerns an Indian attack on a settler's cabin. The second tells of a wagon train, facing various perils, including another Indian attack and running out of water. In a melodramatic resolution of this latter problem, one man dies and is left behind.

|

| Directed by D. W. Griffith, 1914 |

His final film before leaving Biograph was a two-reeler western, The Battle of Elderbush Gulch (1914). This film featured yet another Indian attack and rescue by the cavalry. It starred Mae Marsh and Lillian Gish.

After that, given the freedom to make the monumental feature-length films he had in mind, D. W. had bigger fish to fry. But before the end of the decade, after the success of Birth of a Nation (1915) and the failure of Intolerance (1916), it was all over.

According to film historian Jon Tuska, what Griffith brought to the western were filming and editing techniques that would make the story more exciting for the audience. As one example, he advanced the art of crosscutting, taking us back and forth between two different threads of action – the embattled settlers and the cavalry racing to the rescue. These techniques he continued to perfect in his feature-length films.

You can see the entire Battle of Elderbush Gulch below. The film's scope is ambitious for a two-reeler, especially as the screen fills with large numbers of Indians and settlers in hand-to-hand combat, horses milling among them, and dust flying.

You can see the entire Battle of Elderbush Gulch below. The film's scope is ambitious for a two-reeler, especially as the screen fills with large numbers of Indians and settlers in hand-to-hand combat, horses milling among them, and dust flying.

|

| Tom Mix, 1919 |

Tom Mix.

Filming on location in Oklahoma, director Francis Boggs found him working as a local deputy sheriff and hired him to handle stock. Asking for a part in the picture, Mix got a scene as a bronc rider in a rodeo sequence. Later the same year, he was starring in a two-reeler, The Range Rider, shot in Missouri.

|

| Released 1920 |

By 1920, when he surpassed William S. Hart in popularity, Mix had accumulated acting credits in something like 235 films, most of them shorts. Of these he’d directed over 100. Like William S. Hart he’d begun featuring his horse, Tony, in the credits.

But unlike the high seriousness of Hart, Mix had a high-spirited, show-business persona. Gone was the realism and sentimentality of Hart’s post-Victorian portrayals. Comparing the two cowboy stars, you see a major cultural shift happening in almost the blink of an eye.

Source: Jon Tuska, The Filming of the West, New York: Doubleday, 1976.

Picture credits:

All images from wikimedia.org

Coming up: More on Rex Beach

Labels:

d. w. griffith,

tom mix,

western movies,

westerns

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Rex Beach

Rex Beach (1877–1949) has been an enjoyable discovery. I’ve started with a collection of his short stories, Pardners, published in 1906. Four of them had already appeared in McClure’s and one in Everybody’s Magazine.

|

| 1906 edition |

Beach was college-educated and an adventurer. He was preparing for a law career in Chicago when he raced off to the Klondike for five years. He never struck it rich as a prospector, but he turned the experience into a best-selling novel The Spoilers, which became a play and then a film. In his time, he was a big deal.

“Pardners.” The title story in this collection takes place in the Alaska gold fields and Seattle. The narrator is a big, rough bruiser, Bill Joyce, who tells of taking a young tenderfoot under his wing. They have mixed fortunes as prospectors, but the real drama involves the young man’s wife back home.

When she won’t answer his letters, he gets so heartsick the two men return to the States. In Seattle, they find her singing in a variety show. She considers the marriage over because of some unflattering photos she’s seen of her husband in the newspaper. In doing a photo feature on life up north, some yellow journalist has made him out to be a carouser and womanizer. Eventually, Bill does his part to reunite man and wife in wedded bliss.

|

| Illustration for the story "Pardners" |

The plot may or may not hold your interest, but the character of Bill Joyce as he tells the story is priceless. Like the Old Cattleman of Alfred Henry Lewis’ Wolfville stories, he is an unfailingly entertaining and colorful yarn spinner.

“Pardners” was made into an Edwin S. Porter film in 1910. It was the first of many of Rex Beach’s stories and novels to be adapted to the screen. The Spoilers appeared first in 1914 and was remade four more times, once with Gary Cooper (1930) and once with John Wayne (1942). Altogether, Beach has 52 writing credits at imdb.com.

“The Mule Driver and the Garrulous Mute.” This is one of four stories in the collection that qualify as westerns. The storyteller again is Bill Joyce. This time he recalls a time prospecting with a different partner, called Kink, in Arizona. The plot is quickly set in motion when Kink happens to shoot and kill an Indian.

Long past the time when this became a criminal offense, Kink evades arrest by making a run for the Mexican border. When soldiers from a nearby fort show up looking for him, Bill covers for his partner by pretending to be mute and mentally deficient.

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

Book: Pasó Por Aquí

There’s a playful mood throughout Eugene Manlove Rhodes’ Good Men and True and Bransford of Rainbow Range. This novel, Pasó Por Aquí is pretty thoroughly serious.

|

| Adobe Church, Cordelia Wilson, New Mexico, c1920 |

It is a study in qualities of character, as it seems to have been understood in the West. And it boils down simply to the Golden Rule. Do unto others. This is Rhodes’ story most often regarded as his best. Though not his last work (it was first published in February 1926 in Saturday Evening Post), it feels like a writer in middle-age looking back over his career.

In 1926, Rhodes was 57 and returning to New Mexico after an absence of twenty years. It’s said that coming back was a disappointment for him. The New Mexico he’d known was gone – gone with Pat Garrett, killed on a lonely road in 1908.

The story. There are familiar Rhodes elements in this story – a man being pursued by the law, detailed descriptions of long rides on horseback, an intelligent and articulate woman, and characters pretending to be someone else, with an assumed name. The location is also familiar, the Tularosa Valley.

|

| Main Street, Hope, New Mexico, c1900 |

Like Good Men and True and Bransford of Rainbow Range, the novel starts with a conversation. This time it’s a scene of idle badinage between a young woman and a young man who is trying to court her. She is a nurse at the Alamogordo Hospital. He is an Easterner, of no particular talent and subscribing to no particular work ethic.

They learn of a robbery that has taken place in Belen, far off in central New Mexico, near Albuquerque. The robber held up a storekeeper at the point of a shotgun, which later turned out to be not loaded. About to be apprehended by a posse, he threw down the money he’d taken and escaped again.

The hero. There’s a comic touch to all this, but the tone turns more serious as the point of view shifts to the young man on the run. His name is Ross McEwen and he’s riding, riding, riding south, until he’s passing through the Tularosa Valley on his way to Mexico.

|

| Yucca, White Sands, New Mexico |

It’s not easy going because the valley has become settled with ranches. He marks his progress by the windmills he steers clear of, staying out of sight of riders he sees in the distance.

He’s hungry and thirsty and his horse is wearing out from the long ride. Eventually, he ends up on foot, crossing the White Sands. There he comes upon an isolated cabin where a Mexican family has fallen sick with diphtheria. And without a second thought, he stays with them, tending to them in a desperate and exhausting attempt to keep them alive.

|

| Pat Garrett |

A signal fire eventually draws to them none other than Sheriff Pat Garrett, who sends his deputy to Alamogordo for food, water, and medical help. Seeing the exhausted young man, he tells him to get some sleep. Though the young man calls himself by another name, it’s clear Garrett knows who he is.

The story resolves itself (again, no spoilers; read it) in a way that’s a lesson in integrity. The black-and-white world of standard brand morality loses traction out here in the West. What we get is a man on the wrong side of the law who behaves heroically, while a law-abiding one (the Easterner) is little better than a jerk.

Western melancholy. Reading about the West, you often find under the can-do surface a deep current of melancholy – a sense of loss. It takes many forms. For some it is about promises unfulfilled, and the West has surely seen as many dreams dashed as fulfilled. Maybe more.

Long before there were environmentalists, westerners lamented the loss of the wilderness, the demise of the buffalo and other wildlife, the loss of the open range and the freedom of the frontier.

It was said of Rhodes that he was a melancholy man himself. It’s not hard to think of reasons. His life was not easy. As the oldest of his siblings, he went to work at an early age. And while people remembered him fondly, he was the kind of person who found solace in books. One gathers that he would have gladly stayed on in college to complete his education if there’d been the money.

|

| After the Snowfall, Cordelia Wilson, New Mexico, c1920 |

In his novels, he seems to create a hero like himself, but who lives in a world cut more to his size. It’s filled with loyal friends, and when he falls in love, the girl has a temperament that suits him, and she loves him back. It’s a comic world, where difficulties are overcome with wit and intelligence. And all is grounded in the New Mexican landscape that he loved.

The melancholy, alas, emerges in Pasó Por Aquí. What is past beyond retrieving, Rhodes seems to be saying, is the West where a person’s character counted. Like Wister in The Virginian, he puzzles over what makes a person “good.” But he comes up with another answer.

In this novel, self-sacrifice while coming to the aid of the undefended is the evidence of true worth in an individual. To give all where it’s needed is the true test of moral integrity. It matters more than reputation, which may be either good or bad, and it outweighs any misdeeds that may get someone into trouble. What this resembles is the unwritten Code of the West, which existed before the arrival of the law.

Maybe it’s a sentimental view – the good-bad man we often find in westerns. But Rhodes frames it in a much larger vision. The perspective is that of not just a single lifetime but of time itself. Surely the vastness of the western landscape invites this point of view.

|

| El Morro, western New Mexico |

Summing up. The title of the book, as one of the characters explains, can be found among the inscriptions on a sandstone bluff in western New Mexico. Since Spanish colonial times, it’s been known as El Morro (The Headland). It stands today on the Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation.

|

| Inscription, El Morro, 1709 |

For centuries, travelers who have stopped there for water have left their mark on the stone. Pasó por aquí. I passed by here. In the novel the phrase becomes the summing up of a life. Everything we do adds up to this simple fact. We come, we go, and in the meantime, while we are here, we can choose to give more than we take.

Rhodes lived only a few years in New Mexico and then moved on with his wife to Pacific Beach, California, near San Diego, where he died in 1934. He had been in poor health and was penniless. At his request, he was buried on the site of his old ranch in the San Andres Mountains. On his gravestone are the words, Pasó por aquí.

A few of Rhodes stories were made into films. This novel was adapted and released in 1948 as Four Faces West, with Joel McCrae as Ross McEwen and Charles Bickford as Pat Garrett. I'll be getting back to this story when I've had a chance to see it.

Meanwhile, anyone wishing to do some in-depth research on this well-deserving western writer will find what sounds like a truckload of his papers, letters, photos, and manuscripts at the Huntington Library in San Morino, California. The catalog mentions seven boxes of material, with a total of 1,433 items.

Meanwhile, anyone wishing to do some in-depth research on this well-deserving western writer will find what sounds like a truckload of his papers, letters, photos, and manuscripts at the Huntington Library in San Morino, California. The catalog mentions seven boxes of material, with a total of 1,433 items.

Further reading:

WPA interviews with people who knew Rhodes as a young man

WPA interviews with people who knew Rhodes as a young man

Picture credits:

1) Adobe Church, Cordelia Wilson, New Mexico, c1920

2) Hope, New Mexico, c1900, freepages.family.rootsweb.ancestry.com

3) Yucca, White Sands, wikimedia.org

4) Pat Garrett, wikimedia.org

5) After the Snowfall, Cordelia Wilson, New Mexico, c1920, wikimedia.org

6) El Morro National Monument, Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation, NM, wikimedia.org

7) Inscription at El Morro, nps.gov/elmo

Coming up: Rex Beach's story collection, Pardners (1906)

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Bransford of Rainbow Range, part 2

Rhodes' novel first appeared as a five-part serial called "The Little Eohippus" in the November and December 1912 issues of Saturday Evening Post. When it was published in book form the following year, it went by the title Bransford in Arcadia, or The Little Eohippus. Arcadia is the name of a town where some of the story takes place. The eohippus is the name given to the ancestor of the horse. It was a small mammal with toes instead of hooves.

I’ve got a bunch more post-its sticking out of my copy of this novel for details that want to be included here, but I’ll end with this one. I think it sums up Rhodes perfectly. As Jeff is crossing the Rio Grande, he takes a book from his pocket and puts it under his hat, to keep it dry. The book is Alice in Wonderland.

I’ve got a bunch more post-its sticking out of my copy of this novel for details that want to be included here, but I’ll end with this one. I think it sums up Rhodes perfectly. As Jeff is crossing the Rio Grande, he takes a book from his pocket and puts it under his hat, to keep it dry. The book is Alice in Wonderland.

|

| Charlotte Perkins Gilman, c1900 |

It plays a part in the plot as a pocket-size turquoise figurine carried by Jeff Bransford. Its role is occasion for a verse that gets quoted in the novel:

Said the little Eohippus;

“I’m going to be a horse!

And on my middle fingernails

To run my earthly course!”

The lines are from a poem, “Similar Cases,” by American sociologist and writer, Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860-1935), an early feminist.

You can make a little or a lot out of all this. The oddness of a small horse with toes reflects something of Rhodes himself, the book-reading cowboy with two years of college and a head full of ideas. He also shows no discomfort putting the words of a feminist writer into the mouth of his cowboy hero.

Romance. All of which brings us to the role played by Ellinor Hoffman, the young woman who falls for him and gets him into so much trouble. Of all the early western fiction I’ve read so far (and I’ve still got a ways to go), Ellinor fits most easily into a cowboy world.

|

| Young Woman in Green, William Glackens, c1915 |

She is intelligent and resourceful – in ways we don’t fully appreciate until the end of the novel. She’s also “finished,” in the way that word used to mean. Pretty as a picture, clever, witty, and a match for Bransford. She falls in love with him at first sight, as he does with her.

The nearest thing like them is B. M. Bower’s two sweethearts in her Chip of the Flying U. Only her story is more of a ranch romance. Bertrand Sinclair, in Wild West, also has this kind of love-story somewhere in mind, but the sweetheart of his cowboy hero is a marginal character. Added value, but not central to the story.

Owen Wister may also have been trying for this kind of romance. The Virginian has a similar chivalrous respect for a woman’s honor. Just as he lights into Trampas for an ungentlemanly remark about the schoolmarm, Jeff defends Ellinor. After an ungracious remark by a companion, he says, “If you slur that girl again I’ll not shoot you – I’ll naturally wear you out with this belt.”

But Wister’s romance is weighed down under class differences and the old East vs. West debate. His schoolmarm Molly is hard to like, and the Virginian’s affection for her hard to fathom. When she finally agrees to marry him, it’s only after he’s exhausted all her defenses.

I’m guessing we’re seeing two influential women from Rhodes’ life in his fictional Ellinor. One is his mother, a woman well educated by nineteenth-century standards and something of a free-thinking activist during her lifetime. The other was his wife, a widow with two sons, who first came to know him through his poetry.

|

| The Real Thing, 1900 |

They fell in love at long distance through the U.S. mail. From the evidence, she was also no shrinking violet, but a force in his life that got him to leave New Mexico to live near her family in upstate New York. She also stood by him through what must have been difficult years of marriage – Rhodes was no great provider. And she’s remembered as a generous keeper of his literary legacy after his death.

The romance between Bransford and Ellinor is greatly idealized, but it reveals a lot about Rhodes’ view of women. They can be both disarming and irresistible, yes, but Rhodes doesn’t just idealize them. If Ellinor is any example, they are easily the equal of men in intelligence and courage. Maybe even a little more than equal.

More fun. Rhodes apparently has long had a following among readers familiar with the cowboy West. Hard to put your finger on it, but it surely has something to do with his kind of ironic, tongue-in-cheek humor. With his love of language, he can surprise you with where he’s going with a sentence.

When Jeff and Ellinor first meet, the “delicious intimacy” quickens his pulses “to a pleasant flutter” and causes “a certain tough and powerful muscle to thump foolishly at his ribs.” The organ under question goes unnamed there, but you understand that his physical reaction affects not just his heart.

|

| Photo by Erwin Smith, 1909 |

Rhodes’ narrator occasionally interrupts the telling of the story to chime in, reminding us of ourselves, his readers. After Jeff persuades her to sing him a song, Rhodes declines to describe the sound of it:

No, you shall not be told of her voice. Perhaps there is a voice that you remember, that echoes to you through the dusty years. How would you like to describe that?

By that question, I think we are invited to participate in imagining the scene ourselves. Later, when Billy, a young rival of Jeff’s affections, makes an extra effort to arrest Jeff after the robbery, the narrator playfully butts in again:

How old are you sir? Forty? Fifty? Most actions are the result of mixed motives, you say? Well, that is a notable concession – at your age. Let it go at that. Billy, then, acted from mixed motives.

Later again, when Jeff is giving the prospector’s camp a lived-in look, the narrator remarks:

He took the little turquoise horse from his pocket and laid it in the till of the violated trunk. Were you told about the violated trunk? Never mind – he had done any amount of other things of which you have not been told.

Talk about withholding information. And Rhodes pulls a fast one as Jeff befriends two of the men who are part of the search party looking for him. After he presents himself as a prospector by the name of Tobe Long, the point of view shifts to Griffith, one of the two men.

|

| Cowboy, c1901 |

For pages, we observe Jeff only through the eyes and gut feelings of Griffith, who is torn first this way and that by his suspicion that this prospector is really the Jeff Bransford they’re looking for. Dramatic irony is often fun, and this is a cleverly entertaining example.

The narrative voice in Rhodes stories reminds me a lot of Baxter Black and any number of modern-day cowboy poets who are masters of ironic storytelling. They use the same verbal flights to pump drama into humorous accounts of everyday western life. Here a horse named Goldie throws Jeff Bransford/Tobe Long:

Mr. Long sat in the sand and rubbed his shoulder: Goldie turned and looked down at him in unqualified astonishment. Mr. Long then cursed Mr. Bransford’s sorrel horse; he cursed Mr. Bransford for bringing the sorrel horse; he cursed himself for riding the sorrel horse; he cursed Mr. Griffith, with one last, longest, heart-felt, crackling, hair-raising, comprehensive and masterly curse, for having persuaded him to ride the sorrel horse. Then he tied the sorrel horse to a bush and hobbled on afoot, saying it all over backward.

Details. Despite the adventure and romance in the story, it has a lived-in feel as well. The landscape is so meticulously detailed, readers today say they can pick out the views of the Tularosa Valley Rhodes is describing. His description of the mining camp reveals a photographic memory for detail as well. Right down to the miner’s supper of canned corn fried in bacon grease.

I’ve got a bunch more post-its sticking out of my copy of this novel for details that want to be included here, but I’ll end with this one. I think it sums up Rhodes perfectly. As Jeff is crossing the Rio Grande, he takes a book from his pocket and puts it under his hat, to keep it dry. The book is Alice in Wonderland.

I’ve got a bunch more post-its sticking out of my copy of this novel for details that want to be included here, but I’ll end with this one. I think it sums up Rhodes perfectly. As Jeff is crossing the Rio Grande, he takes a book from his pocket and puts it under his hat, to keep it dry. The book is Alice in Wonderland.Further reading:

W. H. Hutchinson. A Bar Cross Man: The Life and Personal Writings of Eugene Manlove Rhodes. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1956.

Image credits:

Coming up: Rex Beach and more early western movies

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)