Just in time for Halloween: a Shirley Jackson story, "The Bus" from The Saturday Evening Post.

Just in time for Halloween: a Shirley Jackson story, "The Bus" from The Saturday Evening Post.Saturday, October 30, 2010

James Reasoner, Dust Devils

Today’s post may seem off topic, but I’m making a cowboy-up effort here to corral it in. Waiting to get around to a couple of James Reasoner’s historical novels that came from AbeBooks, I picked up a copy of his Dust Devils, a bit of crime fiction set in modern-day Texas – which you quickly recognize as no-country-for-old-men country.

I’m not the crime fiction expert in the household, so I feel free to wander way off that range and over the divide to this one. Having vicariously spent some of my summer with Billy Bonney, I’m easily reminded of the Kid as I read Reasoner’s sharply written noir story of a modern-day “kid” drawn not all that reluctantly into a career of crime.

I will throw Jim Thompson into the mix here, too. In particular his ethically challenged sheriffs of small Texas towns, like the one in Pop. 1280. And I’ll put on James McMurtry’s “Choctaw Bingo” while we consider this whole phenomenon of the Old outlaw West still at large today.

Reasoner captures nicely the mentality of a young drifter, Toby, who has no attachment to his past and no apparent direction for the future. Arriving at a farm in West Texas, he takes a job as a hired hand for a middle-aged woman who lives there alone. Before long, he’s left his bed at night for hers. The sex is good and so is life.

Of course, this ends abruptly. Toby and the woman and her two dogs are soon fleeing the scene of a crime, leaving behind the bodies of two would-be killers and a cop. Toby starts out as an accomplice and, as the story swiftly progresses, gets drawn deeper and deeper into a murderous settling of scores among a nest of cold-blooded bank robbers.

That’s enough of the plot to get us going here. I won’t give away any more of the surprises and sudden twists and turns. There are plenty more in store for any reader who has the temerity to pick up this fast-moving thriller.

Friday, October 29, 2010

Casual Friday: A year of books

I had a birthday this week. Following the example of Charles Gramlich, I decided to consider the past year in terms of the books I’ve read.

Twelve months ago, I was reading a mix of books about the West and translations from Arabic. Mid-year, I started this blog about pre-Hollywood western writers. So, below I’m listing a baker’s dozen that I liked the best from before and after heading down "western avenue." The titles are in alpha order because it would be too hard to rank them. They’re all “5-stars”:

Coming up: William MacLeod Raine, Brand Blotters (1911)

Twelve months ago, I was reading a mix of books about the West and translations from Arabic. Mid-year, I started this blog about pre-Hollywood western writers. So, below I’m listing a baker’s dozen that I liked the best from before and after heading down "western avenue." The titles are in alpha order because it would be too hard to rank them. They’re all “5-stars”:

Arabesques by Anton Shammas

I flat out loved this book from page one. Above all it is a celebration of storytelling itself, as its free-associating narrator weaves together an intricate pattern of stories that make up three generations of family history. The overall narrative jumps backward and forward in time, making connections between incidents and people across decades. Meanwhile, 20th century history is rapidly redrawing the map where it all takes place – its Arab characters inhabiting a village that finds itself after 1948 part of the new state of Israel.

Arizona Nights by Stewart Edward White

This 1907 book is a series of campfire stories told by several cowboys who work together for a ranch owner in southeast Arizona. The stories are of various kinds, ranging from personal experiences to tall tales to a real pulp-style adventure. Linking them together are descriptions of the Arizona desert and a long, detailed description of an open range roundup. The unnamed cowboy narrator captures the rhythm of the work and the feelings that go along with it – the excitement, the exertion, the exhaustion, the camaraderie.

Breaking Smith’s Quarter Horse by Paul St. Pierre

This entertaining novel is set in the 1950s in “Cariboo Country” of central British Columbia. First published in 1966, it is full of quirky ironies and self-deprecating humor I can only describe as “Canadian.” Smith is a small rancher, with horses, Herefords, and hayfields in a mountainous area known as the Chilcoton. He gets involved in a murder trial in which the defendant is an Indian.

Cattle, Horses and Men by John H. Culley

An excellent memoir and reminiscence of frontier ranching and cowboying, loaded with Old West information and written gracefully and intelligently by its author. John (Jack) Culley came out West from a wealthy family in northern England, and at the age of 30 he was already range manager at the massive Bell Ranch in northeast New Mexico. The book was first published in 1940, so Culley is looking back over a half century of history.

The Cowboy Humor of Alfred Henry Lewis

This is a modern-day anthology of stories taken from three books c.1900 by Lewis. The narrator is an old Texan known only as “the Cattleman.” His humorous yarns are usually about the dozen or so colorful characters who live in or pass through Wolfville, a frontier town not unsimilar to Tombstone, Arizona.

Death and the Dervish by Mesa Selimovic

This classic novel, written during the Soviet era in Yugoslavia, is set in an unnamed city that seems to be 17th-century Sarajevo. Its narrator, Sheikh Ahmed, is tormented by his emotional conflicts, and much of his account of himself reads like Edgar Allan Poe. For 455 pages the reader is immersed in the twists and anxious turns of living in a police state and under the thumb of an oppressive foreign power.

My Father's Paradise: A Son's Search for His Family's Past by Ariel Sabar

The American son of a Kurdish immigrant family in Los Angeles reconstructs his grandparents' and his father's lives in northern Iraq and Israel. His father, by chance, becomes the world’s authority on ancient Aramaic, which was spoken until modern times in his village. Besides a fascinating biography, it is also about the deepening relationship between a father and his grown son. Blew me away.

An Obituary for Major Reno by Richard S. Wheeler

This well researched historical novel gives an account of Major Marcus Reno, one of the commanding officers with Custer at Little Bighorn. The loss of Custer and the scale of the defeat led almost immediately to finger pointing, and Reno found himself to blame. The mixture of character flaws in an otherwise commendable officer led to his eventual discharge from the Cavalry. He spent the rest of his life trying to regain his lost honor. Richard Wheeler tells his story with a remarkable appreciation for a difficult and complicated man.

The Outlet by Andy Adams

Adams had been a cowpuncher on trail drives and wrote from firsthand experience. He intended with his fiction to correct the romanticized view of the West being created by Owen Wister and others. Published in 1905, this is a trail drive novel, and a sequel to Adams’ The Log of a Cowboy. The narrator, Tom Quirk, is a young cowboy in his twenties who gets his first job as trail boss, taking a herd in 1884 from west Texas to Dakota Territory.

Pasó por Aquí by Eugene Manlove Rhodes

I read three of Rhodes’ novellas and found them equally good. This one from 1926 is regarded as a classic of Western fiction. It tells of a young fugitive from the law who stops to help a family with diphtheria. The law, in the form of Pat Garrett, catches up with him, and there follows a very “western” form of law enforcement.

Pulp Writer by Paul S. Powers

Written during the early 1940s, this is a memoir of how the author found success as the creator of western heroes during the heyday of the pulps. He describes how he learned to master the short fiction formulas that put him in demand by one of the most popular of the story magazines, Wild West Weekly. Laurie Powers' account of her discovery of her grandfather's career, his papers, and this unpublished manuscript, provide a fascinating story of its own.

This Side of Innocence by Rashid Al-Daif

There’s more Edgar Allen Poe and a heavy mix of Kafka in this novella by Lebanese author Al-Daif. An ordinary man finds himself in the grip of a nightmarish tyranny, in which he is as much the victim of himself as that of a brutal modern state. On one level, it's a suspenseful political thriller. On another it explores the fine line between guilt and innocence, as the man’s interrogators are determined to get potentially incriminating information.

To Hell on a Fast Horse by Mark Lee Gardner

New Mexico during 1870-1910 had its share of criminals – on both sides of the law. Pat Garrett, a gambler, speculator, one-time buffalo hunter, and part-time lawman was one of the few with the determination to take on some of them – and one in particular, Billy the Kid. Gardner has written a well-researched book about both men. His account is a happy mix of history and good storytelling.

Photo credit: By the author. This Western Avenue is in LA, extending many miles from Griffith Park down to San Pedro. I cross it every day to and from work. It even has its own wikipedia page.

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Western Literature Association

The Western Literature Association has been meeting over in Prescott, Arizona. Some among this group of scholars have been happily reinventing the whole idea of American literature. The WLA blog reports a panel discussing the pioneering work of Annette Kolodny who wrote an influential article in 1992, “Letting Go our Grand Obsessions.”

She challenged back then a bunch of “grand” notions about what folks mean by “American literature.” One of them is the idea of “the frontier.” And since that’s a word that gets kicked around a lot in talk about westerns, I wanted to devote a few words to it here.

A new frontier. Kolodny argued that the frontier is not just the unsettled areas at the advancing edge of “civilization.” It exists in a geographical area, yes, but it’s not that area itself. It’s the place where different cultures come into contact and begin to merge. Think of Tex-Mex and you have an example.

Another example even closer to BITS is the absorption of vaquero culture and practices into what became the American cattle industry. Just think of all the Spanish words absorbed by cowboys into the English language: rodeo, lariat, ranch, buckaroo. A Texan version of this culture then traveled northward as far as Canada with the cowboys who adopted it.

We are used to thinking of this as a “dominant” culture and its language taking what it needs from a lesser one. Kolodny would see it as only another example of how cultures blend at the boundaries – a process that continues today in the multi-lingual Southwest and California. And with every new wave of immigrants to the New World, there are still those boundaries of contact. The frontier, she says, never closed.

She also reminds readers that Native American cultures had been bumping up against each other for centuries before the arrival of Europeans. There was a vast network of trade routes along which cultures and their products and technologies spread. Indians were accustomed to encounters with “foreigners,” whether friendly or hostile.

And one other thing to remember: the Native American populations were reduced more by “foreign” microbes than foreigners themselves. Europeans brought a kind of Black Plague with them that wiped out as much as two-thirds of those who were here first. This resulted in the impression among early explorers that the western frontier was virtually “empty.” It hadn’t been.

American literature, Kolodny says, has been whatever’s recognized as literary at the English-speaking urban centers. As a result – big surprise – any literature that came from points of contact with other cultures has been regarded as regional or “marginal,” and therefore of lesser importance. Maybe not even literature at all.

Connecting the dots. It’s early for me to be doing this, but I start connecting some of these ideas with the western fiction I’ve been reading. Some things pop out right away.

Life on the margins, Kolodny points out, is first about encounters with “foreign” landscapes and geography. This subject is often celebrated in western fiction, where stories involve individuals in a vast wilderness terrain or at the mercy of the elements. Thus, the little settlement that’s the only sign of human life from horizon to horizon came to represent “the frontier” in the American imagination.

More complex is the debate often going on in this fiction between Eastern and Western values. Or to use Kolodny’s terminology, think of it as a dialogue between the center and the margins.

Whether writers were Easterners or Westerners, the book-buying public was in the East. And it was the Eastern-based editors who were selecting what got into print. We can assume what they picked was their idea of what would sell.

So what we get in western fiction is what would fit Eastern notions of the frontier. And that includes the racial biases and the appearance of Native Americans, African Americans, Asians, “half-breeds,” and Mexicans as little more than cardboard stereotypes. There are exceptions, but they are not many.

The notion of a “half breed,” in fact, seems to have been the most repellant of all for readers, since that’s the way this individual is cast in novels. The French-Indian central character in Stewart Edward White’s The Westerners is supposed to make your skin crawl. White even explains the genetics that account for his amorality. It’s a short step from that to a similar view of any cross-cultural output. (Scholars, by the way, like to use the term “hybridizing” when cultures meet and mix.)

So the western novel is constrained by the assumptions of the East, and they come together in a myth about racial, cultural, and technological dominance over inferior peoples. Some readers and moviegoers still prefer that myth. It would be interesting to measure how much the early western helped create it. Meanwhile, scholars of American Literature are shaking things up in a way that may eventually create some new myths.

Further reading:

Annette Kolodny. “Letting Go our Grand Obsessions: Notes Toward a New Literary History of the American Frontiers,” American Literature 64.1 (1992), 1-18.

Image credits:

1) Book cover from Yellow Star: A Story of East and West (1911) by Elaine G. Eastman. Eastman was a teacher among the Lakota Sioux and wife of Native American physician Charles Eastman. Illustrators, Angel de Cora and William Henry "Lone Star" Dietz. Source: wikimedia.org.

2) Sioux tipis, Karl Bodmer, 1833; wikimedia.org

3) I Know'd It Was Ripe, Thomas Hovenden, c1885, Brooklyn Museum; wikimedia.org.

2) Sioux tipis, Karl Bodmer, 1833; wikimedia.org

3) I Know'd It Was Ripe, Thomas Hovenden, c1885, Brooklyn Museum; wikimedia.org.

Coming up: A Year of Books

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Black Cowboys of Texas, part 2

I’ve read more of Black Cowboys of Texas, which I discussed in the last post. This time, I read through the middle section, “Cowboys and the Cattle Drives,” which includes profiles of eleven men who were drovers during the trail drive years, 1867-1885.

According to the writers, black cowboys were typically skilled at breaking horses. Many also worked as cooks on the trail, one of whom is profiled in the book. In general, a black member of an outfit was expected to do the work that the white men preferred not to. John Hendrix, writing in 1936, is quoted in the book as saying:

This most often took the form of “topping,” or taking the first pitch out of the rough horses of the outfit as they stood saddled, with back humped, in the chill of the morning, while the boys ate their breakfast . . . It was the negro hand who usually tried out the swimming water when a trailing herd came to a swollen stream or if a fighting bull or steer was to be handled, he knew without being told it was his job (p. 194).

The men who are remembered were also top-notch riders and ropers. Their stories were often recorded because they were favorites of their white employers.

Color. This favoritism figured into the way they were accepted by white cowboys and others. It has been said that race relations on the trail were somewhat relaxed, but the evidence shows otherwise. A black man could be a trail boss only for other black cowboys. White cowboys would not take orders from him.

Color could prevent him from being served at a bar in a cow town. He might be challenged to a fight by another cowboy who objected to his taking an “inappropriate” liberty. He’d have to duck out of a confrontation, unless he was good with his fists or fast with a gun. Even then, he’d want a white boss or the white cowboys of his outfit for backup.

The black cowboys we meet in this section tend to be loners. Partly accepted by others in the outfit, they might not identify with other blacks or even associate with them. Of these, many had their closest personal ties to the owner, who relied on them as trusted companions. This may well be a hangover from slavery days, which had officially ended only a handful of years previous.

Cattleman Charles Goodnight had such a man in Bose Ikard, a mixed-race son of a Mississippi plantation owner. Ikard, at age 19, joined 30-year-old Goodnight in 1866 on a cattle drive along the Goodnight-Loving trail into New Mexico. Like many black cowboys at this time, Ikard had developed his skills tending the cattle and horses during his ranch owner’s service in the Confederate Army.

Goodnight never forgot Ikard. He had a monument erected on his grave in Weatherford, Texas, after his death in 1929. The epitaph read:

Served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior. – C. Goodnight

Readers of Lonesome Dove may well be reminded of Woodrow F. Call’s similar epitaph on the grave marker for the trail drive’s black scout, Deets.

Labels:

black cowboys,

book review,

cowboys,

old west,

texas

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Black Cowboys of Texas

Ever since reading David Cranmer’s terrific story “Miles to Go,” I’ve been wanting to visit this topic. It’s a little off the main trail for me, but I want to take a detour through the subject for a couple posts here at “Buddies in the Saddle.” That topic is Black Cowboys.

I’m starting into a book published by Texas A&M University Press called Black Cowboys of Texas (2000). It’s a lengthy anthology, with profiles of many African American cowmen and a fine selection of photographs. The work of 27 different authors, it’s edited by Sara Massey, who until retirement was curriculum specialist at the Institute of Texan Cultures, University of Texas at San Antonio.

Drawing on WPA materials, interviews, and documented sources, the book tells of the African Americans who worked cattle on the plains and prairies of Texas. Contributions are grouped chronologically: “The Early Cowboys,” “Cowboys of the Cattle Drives,” and “Twentieth Century Cowboys.”

Just reading the Preface and the Introduction to Part I, you get enough information about Black history in Texas to undo many notions from all-white Hollywood westerns and genre fiction.

Some myth-busting. As long ago as the Spanish colonization of Texas in the 18th century, there were black and mixed-race people living there. A census in 1792 recorded almost 3,000 residents of the colonial settlements. Fifteen percent of them were of African descent or mixed race.

After Independence from Spain in the early 19th century, there was an influx of newcomers from the Southern States. These were slave owners, and by 1836, when Texas became an independent republic, slaves numbered about 5,000. These mostly worked the white-owned plantations and farms, while a few herded cattle, mostly on foot, in the prairies along the Gulf Coast and the frontier.

By 1850, when Texas had joined the Union, slaves numbered 58,000. Ten years later, on the eve of the Civil War, this number had grown to 182,000 and amounted to 30% of the entire population. From colonial days there had been blacks who were free-men in Texas, yet by this time records show that there were maybe only 355 of them, and the number was dwindling. Meanwhile, a few thousand slaves are believed to have fled to Mexico, Kansas, and Indian lands.

Emancipation came with the defeat of the South, but conditions for blacks did not significantly improve. They could not vote, testify in court against whites, or share public accommodations. And conditions for their labor remained much the same. Violence against blacks often took the form of lynchings, and the KKK emerged as a vigilante presence.

Labels:

black cowboys,

book covers,

book review,

cowboys,

old west,

texas

Monday, October 25, 2010

B. F. Day, Gene Rhodes Cowboy

This curious biography of writer Eugene Manlove Rhodes was published in 1954. Reading it takes you right back to that post-war decade, if you were around then, for Day was a writer for Reader’s Digest. The style and tone of that monthly magazine are unmistakable. It existed at the dead center of American mainstream culture. A wholesome, family-friendly periodical, it embodied the unquestioned values of its middle-class audience. My father, a working man all his life, with an eighth-grade education and a life-long curiosity about most everything, hardly missed an issue.

In this splintered age, it’s hard to imagine a publication that appealed to such a huge popular audience. But it did. It even encouraged book-reading of a kind, publishing each month 4-5 current novels in “condensed” form. In my book-starved boyhood, far from a public library or bookstore, I remember reading them.

Day’s short biography of Eugene Manlove Rhodes brought that all back. Not in a nostalgic way, but as an object lesson in how the values of a time and place get embedded in a writer’s tone, style, and choice of details.

To meet the expectations of her 1950s audience, Day takes a life that was full of contradictions and complications and smooths it all over until it fits into a familiar pattern. In this case, it’s the story of a striver and a scrapper from humble beginnings who makes a name for himself as a writer, with the encouragement of a loving wife.

To meet the expectations of her 1950s audience, Day takes a life that was full of contradictions and complications and smooths it all over until it fits into a familiar pattern. In this case, it’s the story of a striver and a scrapper from humble beginnings who makes a name for himself as a writer, with the encouragement of a loving wife.

The wife. Rhodes’ widow, May, apparently contributed generously to the writing of this book. Day dedicates the book to her. In 1897, she was recovering from an illness, the mother of two boys by a previous marriage, and wrote Gene a fan letter after reading two of his published poems.

His reply to her was 20 hand-written pages, signed “Love, Gene,” and a long-distance romance bloomed between them. The only thing separating them was 2,000 miles. She lived in Apalachin, New York. After marrying in 1899 and living together in New Mexico for a while, they both returned East so May could look after her ageing parents. And so Gene gave up cowboying and became a farmer, devoting what time there was to writing – and amusing himself .

Labels:

book review,

cowboys,

eugene manlove rhodes,

western writers

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Elmore Leonard story

The Saturday Evening Post website has put up a 1956 western by Elmore Leonard, "Moment of Vengeance." Fans of this first-rate short story writer should be interested.

Friday, October 22, 2010

Casual Friday: Book covers

One drizzling autumn afternoon this week I was leaving the local branch of the library and stopped to look through the boxes of free books that are always in the entryway. I usually find nothing to take home. But this time there were several paperbacks from the 1960s that brought back memories of college days. For anyone around then, caring for a bit of nostalgia, I'm posting them below.

Then there were these two little Bantam books from the 1940s:

The copy on the back of the last one reads: "Four Bantam Books are published each month. Like this book, all are chosen to give you maximum reading enjoyment.

"Bantam Books include novels, mysteries and anthologies, besides works of humor and information. You can recognize Bantam Books by the tasteful pictures on the covers, by their famous authors, and by the tough bantam rooster on the front of all the books. Look for the four new Bantam Books this month, next month, and every month."

And each for only 25 cents. It was a different time.

Coming up: B. F. Day, Gene Rhodes, Cowboy

Then there were these two little Bantam books from the 1940s:

The copy on the back of the last one reads: "Four Bantam Books are published each month. Like this book, all are chosen to give you maximum reading enjoyment.

"Bantam Books include novels, mysteries and anthologies, besides works of humor and information. You can recognize Bantam Books by the tasteful pictures on the covers, by their famous authors, and by the tough bantam rooster on the front of all the books. Look for the four new Bantam Books this month, next month, and every month."

And each for only 25 cents. It was a different time.

Coming up: B. F. Day, Gene Rhodes, Cowboy

Thursday, October 21, 2010

John Sinclair, Cowboy Riding Country

John Sinclair (1902-1993) was a Scotsman who settled in New Mexico in the 1920s and became that rare combination of cowboy and writer. He explains in this collection of essays how real cowboys of his youth scorned writing as "foofaraw," yet his admiration for them is untempered.

Unschooled men of remarkable toughness and skilled at working cattle, especially those who lived through New Mexico's lawless frontier years, they achieve heroic dimension in these pages. Sinclair also writes here of his life as a kind of western H. D. Thoreau, living a young bachelor's life in a mountain cabin west of Roswell, NM.

Meanwhile, he cowboys for enough pay to buy grocieries and essentials (and he remembers the price of everything). There are descriptions here of neighbors and acquaintances, including an old Mexican with a fearful reputation who calls Sinclair "amigo," and a family who asks him to play Santa Claus for their kids with hilarious results.

There are rhapsodic descriptions of New Mexico and nostalgic histories of the ranchers who settled the Pecos River Valley. A resident of Lincoln county, Sinclair devotes many pages to a retelling of Billy the Kid's story. There are ghost sightings from 1906 and recollections of the songs sung by cowboys on the open range,

He gives tribute to a family of expert saddlemakers and remembers an aging rancher still seeking the company of working cowboys in his last days. Finally, he writes two contrasting chapters on a remote desert location that became the site of the first nuclear explosion in 1945, an event that in his view brought an end to a world he obviously loved deeply.

Eager to share his extensive knowledge of New Mexico and Arizona history, Sinclair writes sometimes at great length. His book is illustrated with many nicely rendered drawings and paintings by artist Edmond Delavy. Sinclair has another memoir, A Cowboy Writer in New Mexico, written when he was ninety. Both are out of print, and shouldn't be.

Coming up: B. F. Day, Gene Rhodes, Cowboy

Unschooled men of remarkable toughness and skilled at working cattle, especially those who lived through New Mexico's lawless frontier years, they achieve heroic dimension in these pages. Sinclair also writes here of his life as a kind of western H. D. Thoreau, living a young bachelor's life in a mountain cabin west of Roswell, NM.

Meanwhile, he cowboys for enough pay to buy grocieries and essentials (and he remembers the price of everything). There are descriptions here of neighbors and acquaintances, including an old Mexican with a fearful reputation who calls Sinclair "amigo," and a family who asks him to play Santa Claus for their kids with hilarious results.

There are rhapsodic descriptions of New Mexico and nostalgic histories of the ranchers who settled the Pecos River Valley. A resident of Lincoln county, Sinclair devotes many pages to a retelling of Billy the Kid's story. There are ghost sightings from 1906 and recollections of the songs sung by cowboys on the open range,

He gives tribute to a family of expert saddlemakers and remembers an aging rancher still seeking the company of working cowboys in his last days. Finally, he writes two contrasting chapters on a remote desert location that became the site of the first nuclear explosion in 1945, an event that in his view brought an end to a world he obviously loved deeply.

Eager to share his extensive knowledge of New Mexico and Arizona history, Sinclair writes sometimes at great length. His book is illustrated with many nicely rendered drawings and paintings by artist Edmond Delavy. Sinclair has another memoir, A Cowboy Writer in New Mexico, written when he was ninety. Both are out of print, and shouldn't be.

Coming up: B. F. Day, Gene Rhodes, Cowboy

Labels:

book review,

cowboy memoirs,

cowboys,

new mexico

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Ralph Moody, The Home Ranch

This cowboy memoir is a bit different from the rest. It is more about ranch work than the open range, and the cattle business is in milk cows rather than raising beef. Notably, "womenfolk" also figure into the picture, a change from the usual all-male accounts of early-days cowboying.

Written more like a novel than a memoir, the book tells of Moody's summer as a very young cowhand on a ranch in the foothills of the Rockies, outside Colorado Springs. The year is 1911 and Moody is just 12 years old, already helping to support his widowed mother.

The book is full of closely observed details about the day-to-day work of ranching with horses. A reader becomes easily immersed in this world and its routines of rounding up, cutting, sorting, and driving cattle, picking and using a string of horses. There are also the adventures occasioned by dust storms, a flooding stream, and getting lost in the mountains while cutting trees for fence posts.

The other ranch hands are well drawn, including a villainous character who starts a vividly described fist fight in the bunkhouse. For the fatherless Moody, the boss and foreman provide the nurturing support needed by a youngster becoming a man.

Meanwhile, the foreman's strong-willed daughter (to whom the book is dedicated) cuts her own wide swath through the story's narrative. Moody, who took up writing in his later years, is a masterful storyteller and makes this bygone world come to life.

Coming up: B. F. Day, Gene Rhodes, Cowboy (1954)

Written more like a novel than a memoir, the book tells of Moody's summer as a very young cowhand on a ranch in the foothills of the Rockies, outside Colorado Springs. The year is 1911 and Moody is just 12 years old, already helping to support his widowed mother.

The book is full of closely observed details about the day-to-day work of ranching with horses. A reader becomes easily immersed in this world and its routines of rounding up, cutting, sorting, and driving cattle, picking and using a string of horses. There are also the adventures occasioned by dust storms, a flooding stream, and getting lost in the mountains while cutting trees for fence posts.

The other ranch hands are well drawn, including a villainous character who starts a vividly described fist fight in the bunkhouse. For the fatherless Moody, the boss and foreman provide the nurturing support needed by a youngster becoming a man.

Meanwhile, the foreman's strong-willed daughter (to whom the book is dedicated) cuts her own wide swath through the story's narrative. Moody, who took up writing in his later years, is a masterful storyteller and makes this bygone world come to life.

Coming up: B. F. Day, Gene Rhodes, Cowboy (1954)

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Emerson Hough, Heart’s Desire (1905)

This is a book about longing. It longs for a time past and a place on the frontier that was like a Garden of Eden. It longs for a kind of utopian community where there is order without the need for law. It’s also about the longing of men and women for each other.

Sentimental journey. It’s a sentimental book and much the product of a Victorian frame of mind. But the sentiment is well earned. It works as hard and as honestly to make a case for its imagined world as the hard-edged cynicism of our own time.

The central character in Hough’s book is a young lawyer in a “quasi mining camp that was two-thirds cow town” called Heart’s Desire in south-central New Mexico. Hamlet might be a better word, both for the town and the main character.

There may be 250 souls in Heart’s Desire. It is a single dusty street following the course of a crooked arroyo. Along it is a string of structures, mostly adobe, plus a few made of logs. The town is nestled in a mountain valley. Above it are mountain peaks, and above them is the pure, blue New Mexico sky. The town is, no doubt, the White Oaks, New Mexico, where Hough lawyered for a brief time in the early 1880s.

The central character is Dan Anderson, a young unmarried lawyer, who much like Hamlet is at loose ends and a shade melancholy. Heart’s Desire is a retreat for him from the heartless world of Yankee capitalism and politics as practiced back in “the States.” It’s also the refuge of a wounded soul rejected in his wooing of a girl, Constance Ellsworth. Her father, a captain of industry, has found Dan unqualified to be his son-in-law.

The heart of the matter. The longing – or heart’s desire – that is the central theme of the novel belongs first of all to Dan. He yearns for recognition of his worth as a man, and he yearns for Constance. But his is only part of a chorus of yearning in the novel. The town itself yearns for a kind of prosperity that would come with the building of a railroad. There are gold and coal in the surrounding hills, and the residents live in hope that they’ll win the interest of “Eastern Capital.”

The theme of yearning plays itself out in other ways, too. For contrast, the cowboy Curly sets his sights on a marriageable girl, whose family arrives in town, and is determined to marry her before even knowing her full name. In fact, she’s never known as anything but “the Littlest Girl from Kansas.” Self-confident in everything, Curly seems to succeed without effort. He becomes a married man in a gap between chapters.

Meanwhile, there are simple luxuries that the residents of Heart’s Desire mostly do without. The purchase of four cans of oysters, a bottle of champagne and a cake to complement a Christmas dinner is cause for great excitement among a small bunch of bachelor friends. The novelty of a new phonograph keeps them entertained for an entire night. On another day, they are attempting to master a recently imported lawn game called croquet.

The most poignant episode in the novel involves Tom Osby, a middle-aged man who seems to have lost track of how often he’s been married – often enough, he says, to be an authority on women. He falls in love with the voice of an operatic singer whose recording of “Annie Laurie” moves him to the depths of his soul.

Like Curly, he goes after what he wants. When he learns that the singer is with a touring opera company, he travels some distance by wagon to find her. Discovering that they are both natives of Georgia, they quickly establish a Southern rapport. And for an evening, she gives him a private concert.

Labels:

book review,

cowboys,

emerson hough,

new mexico,

western fiction,

western writers

Monday, October 18, 2010

Mark Spragg, Where Rivers Change Direction

Mark Spragg is a gifted and thoughtful writer in this collection of essays about his boyhood on a dude ranch in Wyoming. His memories are vivid and precise. The stories he tells are compelling and suspenseful, their resolutions often breathtaking. As just one example, the dangerous hunt for a wounded bear evolves into an evocation of a search-and-destroy mission in Vietnam.

There are many ways to read these essays - as nature writing, coming of age memoir, record of a vanishing way of life. For me, the essays are most absorbing when Spragg tells of his teenage years, working in the all-male world of his father and the cowboys who work for him.

They capture the awkwardness of learning to take on a man's responsibilities when they require a fearlessness and stoic toughness more common to pioneers and the Wild West than the urban environment of most of his contemporaries.

There's a poignance that comes a bit clearer in the final essays, which skip forward in time to the author's middle years. Here you pick up a sense of something gone awry, a disillusionment and a good deal of personal anguish.

There is a winter spent alone in a snowbound house as he recovers from a personal malaise identified by no more than the reference to severe leg pains. In the final chapters, he walks the back roads and irrigation ditches of Powell, Wyoming, in search of some measure of solace while his mother slowly dies of emphysema.

There is a winter spent alone in a snowbound house as he recovers from a personal malaise identified by no more than the reference to severe leg pains. In the final chapters, he walks the back roads and irrigation ditches of Powell, Wyoming, in search of some measure of solace while his mother slowly dies of emphysema.

The title, Where Rivers Change Direction, seems to refer to the Continental Divide. It may also call to mind the watersheds in all our lives that pull us with a gravitational force we don't recognize at the time and come to know only long afterward. This book was a winner of the Mountains and Plains Bookseller Award.

Spragg has gone on to write screenplays and novels set in the West. His novel An Unfinished Life was made into a film with Robert Redford and Morgan Freeman in 2005. An excellent TV movie, Everything That Rises, with Dennis Quaid as a modern-day rancher in Montana was made in 1998.

Coming up: Emerson Hough, Heart's Desire (1905)

There are many ways to read these essays - as nature writing, coming of age memoir, record of a vanishing way of life. For me, the essays are most absorbing when Spragg tells of his teenage years, working in the all-male world of his father and the cowboys who work for him.

They capture the awkwardness of learning to take on a man's responsibilities when they require a fearlessness and stoic toughness more common to pioneers and the Wild West than the urban environment of most of his contemporaries.

There's a poignance that comes a bit clearer in the final essays, which skip forward in time to the author's middle years. Here you pick up a sense of something gone awry, a disillusionment and a good deal of personal anguish.

There is a winter spent alone in a snowbound house as he recovers from a personal malaise identified by no more than the reference to severe leg pains. In the final chapters, he walks the back roads and irrigation ditches of Powell, Wyoming, in search of some measure of solace while his mother slowly dies of emphysema.

There is a winter spent alone in a snowbound house as he recovers from a personal malaise identified by no more than the reference to severe leg pains. In the final chapters, he walks the back roads and irrigation ditches of Powell, Wyoming, in search of some measure of solace while his mother slowly dies of emphysema.The title, Where Rivers Change Direction, seems to refer to the Continental Divide. It may also call to mind the watersheds in all our lives that pull us with a gravitational force we don't recognize at the time and come to know only long afterward. This book was a winner of the Mountains and Plains Bookseller Award.

Spragg has gone on to write screenplays and novels set in the West. His novel An Unfinished Life was made into a film with Robert Redford and Morgan Freeman in 2005. An excellent TV movie, Everything That Rises, with Dennis Quaid as a modern-day rancher in Montana was made in 1998.

Coming up: Emerson Hough, Heart's Desire (1905)

Saturday, October 16, 2010

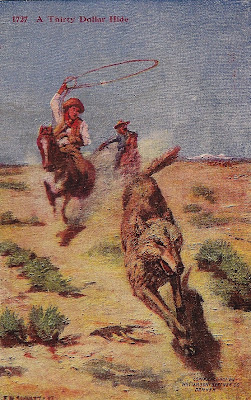

F.W. Schultz, illustrator

Walker Martin asked if I'd post all my F.W. Schultz pics together in a bunch. I'm doing the next best thing, as there are a lot of them. The horizontal pics can all be found in an earlier Buddies in the Saddle post (click here). Below are the vertical ones:

So far, I've turned up not a word of information about the artist. Maybe someone seeing these can shed some light for us.

So far, I've turned up not a word of information about the artist. Maybe someone seeing these can shed some light for us.

Labels:

cowboys,

illustrators,

old west,

western artists

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)